Distribution of MEV Surplus

Who captures MEV? Who should capture MEV?

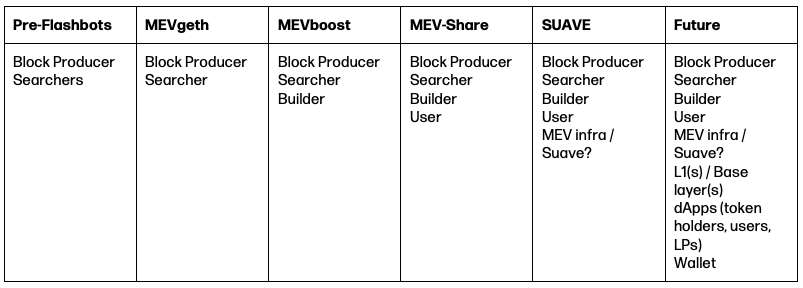

Before Ethereum’s transition to proof-of-stake (PoS), Miner Extractable Value (MEV) was primarily captured by searchers and miners. Today, on Ethereum, network stakeholders known as builders and validators compete alongside searchers for MEV revenue. In the future, there will be even more participants fighting over MEV. This begs a few questions: How is MEV currently distributed between participants? What is the total size of the MEV pie today? What will the total MEV market and its distribution look like going forward?

MEV is Endemic

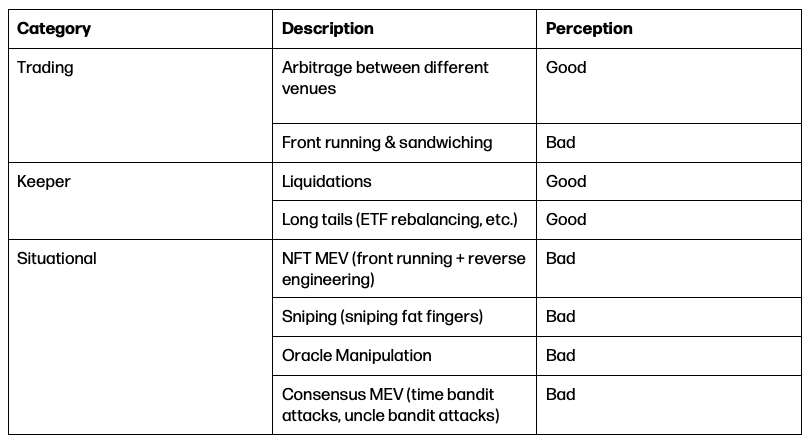

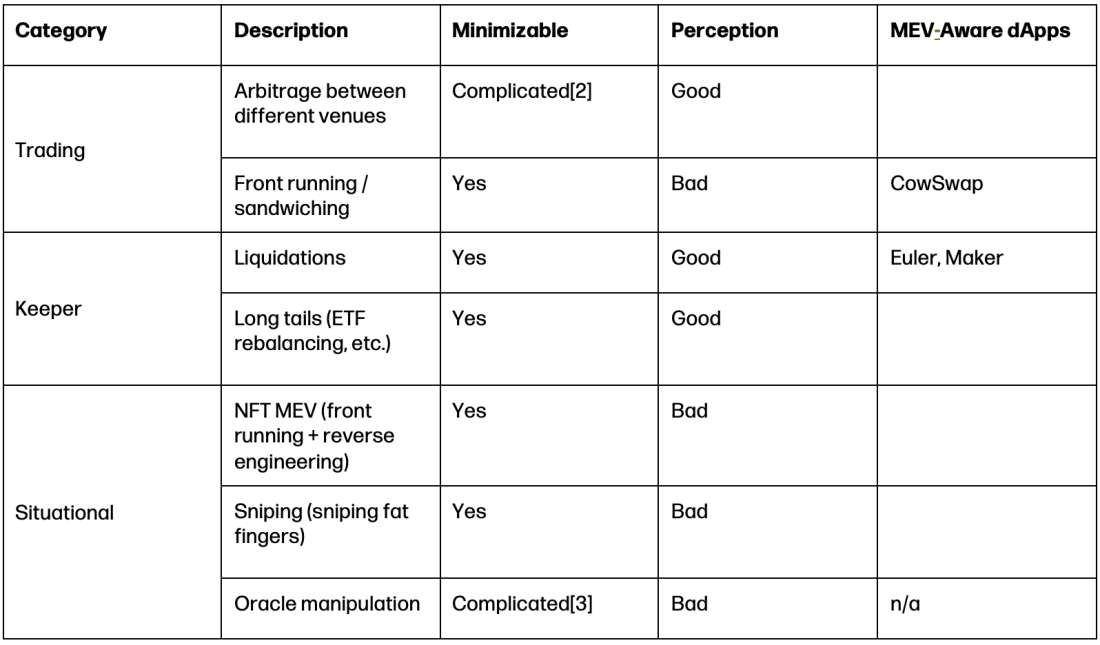

MEV is the surplus value extracted from blockchain systems. As long as there is value transacting through a permissionless system, there is MEV. For example, if a trader sets too high of a slippage setting, a searcher can sandwich their transaction. In this case, the searcher captures MEV at the trader's expense. To explore the factors that shape MEV, it is essential to have a taxonomy that understands the growth and declines of distinct MEV segments.

Although MEV often has negative connotations, MEV can feed into the ecosystem's health. MEV can create incentive alignment for the system’s actors. For instance, without searcher liquidations and arbitrage running between venues, protocols would accrue bad debt, and users would face larger spreads, receiving worse execution onchain.

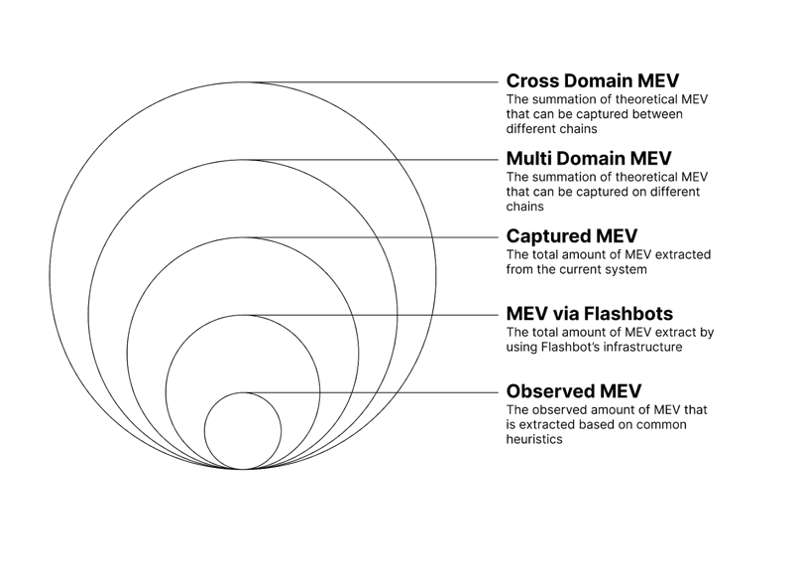

Observable MEV is The Tip of The Iceberg

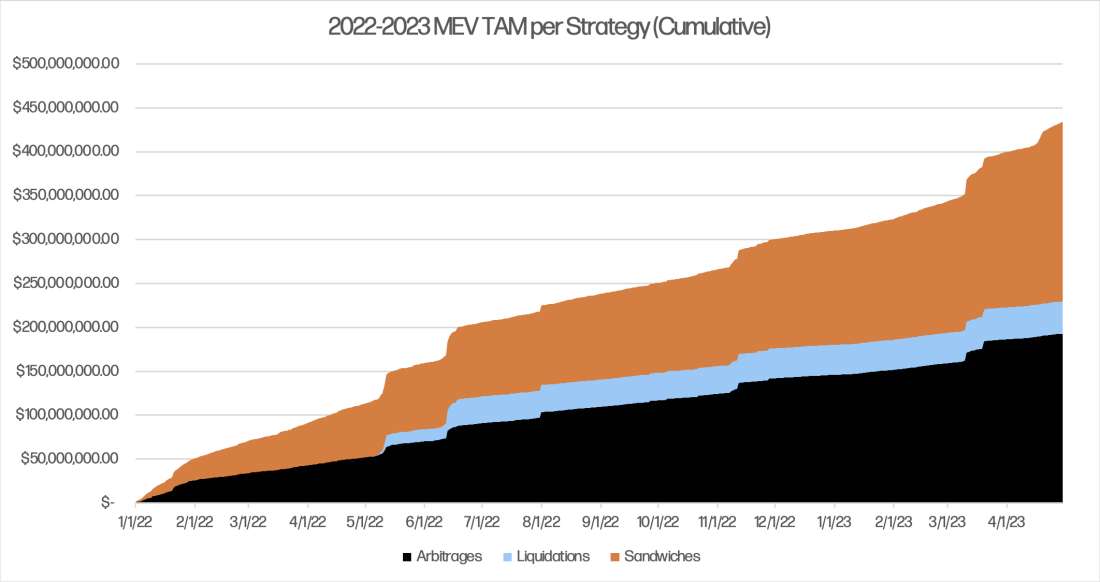

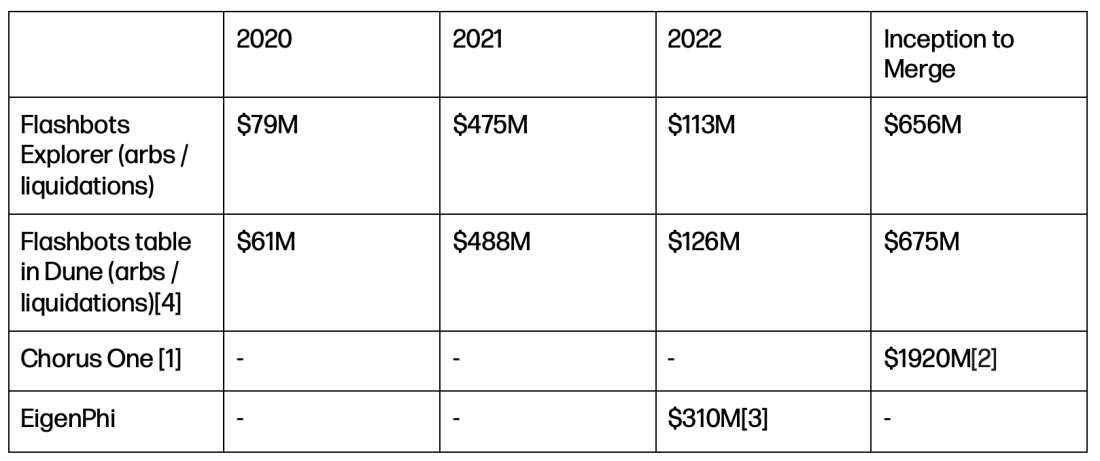

While calculating MEV’s Total Addressable Market (TAM) is challenging, we estimate the lower bound of annual MEV extracted from Ethereum is between $300M - $900M, based on estimates from various data providers [1].

This MEV TAM is the summation of value lost by MEV. For example, if a transaction is worth 100 units of value and the user only ends up with 90 units of value, 10 units of value is leaked to MEV. In practice this is calculated by identifying MEV transactions (e.g., arbitrages, sandwiches, or liquidations) then determining searcher revenue. This number can be further split into searcher profit, builder profit, and net new money to validators.

However, we would estimate that the true MEV TAM is larger than the $300M - $900M spread, and that the 2022 MEV TAM could exceed a billion dollars. Calculating MEV’s true TAM is difficult since MEV analytics are best at identifying MEV that follow predictable or deterministic patterns, such as arbitrages, sandwiches, and liquidations. This does not capture the long tail of MEV with NFTs and other DeFi applications, hence the real TAM is actually larger than the estimates. Today, market participants are increasingly sophisticated as they compete with each other. For example, off-chain hedging cannot be tracked, Multiblock MEV is challenging to identify, and probabilistic MEV is almost impossible to detect.

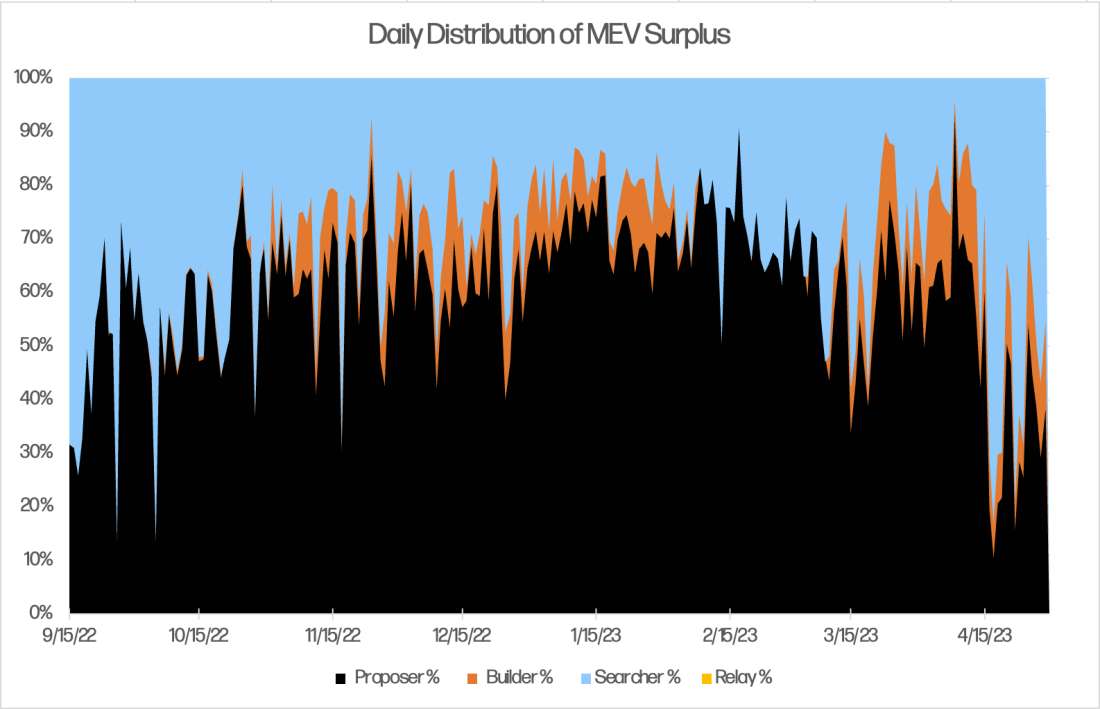

Validators Capture the Majority of MEV

The status quo is that validators (also known as proposers or block producers) capture the majority of Observed MEV. Over time, we have seen profitability shift from searchers to validators and recently back to searchers. Revenue compression is especially apparent for sandwiches and liquidations, as these types of MEV opportunities are highly competitive. Searchers must bid most of their expected value to block producers to ensure transaction inclusion.

However, validators may be taking a smaller slice in practice as the Total MEV is much greater than the Observed MEV. Additionally, the universe of Unobserved MEV tends to be less competitive. Therefore, searchers will not have to bid as much for transaction inclusion.

Who Will Capture MEV in the Future?

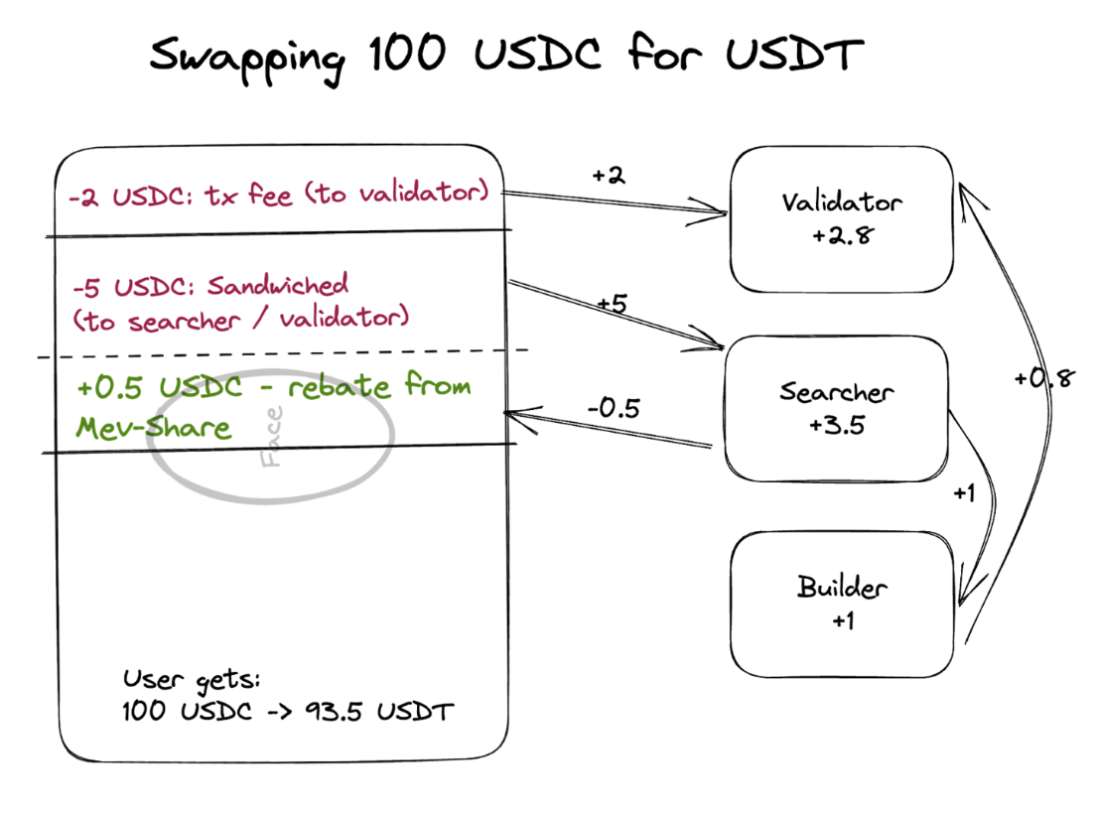

The standard today is that three parties capture MEV – block producers, searchers, and builders. However, there is a prevailing narrative that MEV originators, often the transaction originators, should get rebated for the MEV they generate. MEV-Share is a recent instantiation of this philosophy, where searchers can bid on order flow from users, wallets, and/or dApps. Ultimately, there are market dynamics that drive how much senders get rebated for the MEV they generate and how MEV surplus value is distributed between different market participants. But there is a philosophical question that asks what is the optimal split between MEV originator vs. searchers vs. other parties.

MEV-Aware Apps Will Reduce MEV TAM

However, this debate over fairness and value distribution is likely moot. As multiple parties fight to access the MEV surplus, we expect MEV’s TAM to decrease. From an application or dApp perspective, why should they leak value to searchers when they can keep the value for themselves or their users? These “MEV-Aware” apps will implement features that reduce the MEV they generate.

This is already happening. For example, MakerDAO and Euler both use auctions for liquidations as opposed to lenders Compound and Aave, which set liquidations at a fixed discount. In Maker’s and Euler’s case, because keepers compete on price to liquidate a loan, the liquidated user suffers a reduced loss. In other words, it recaptures value that they would have lost. For Aave and Compound, there is a fixed liquidation discount. This means that the liquidated user suffers a fixed loss, instead of a variable one that is likely less than the fixed amount. As apps compete for users and liquidity, we can expect dApps to implement features that reduce value leakage to encourage usage over competitors.

How will dApps think about allocating value? Instead of having a liquidation auction reduce the loss to LPs, the protocol can implement an auction fee that shifts some value back to token holders.

We expect applications to use a better combination of mechanism design (primarily auctions) and smarter parameter defaults to plug MEV leakage that their users experience. Some examples include UI warnings to prevent fat fingering, volatility, and pool-aware slippage limits for AMMs. The famous 2.08m USDC to 0.05 USDT swap can easily be prevented.

Looking back at our MEV taxonomy, we expect some categories to be easier to minimize than others. For example, front running and sandwiching will be minimized through more intelligent slippage settings. However, some forms of MEV might be inevitable—arbitrage between DEXs, for example, cannot be easily reduced without changes to the base protocol [2].

Who Decides the Future?

The MEV market landscape will continue to evolve going forward and impact various market participants. Many interesting questions remain: How will protocols balance the needs of different user groups and how will value flow between these groups? Will the market decide on what amount of MEV should be returned, or instead will there be intervention by protocol designers? Will users gravitate towards protocols that protect them more from MEV, or will users ultimately not care?

We expect application-specific MEV will approach zero in the medium term. Over the long run, inter-application MEV will slowly shift more value back to the originators of the order flow through protocol design. Ultimately, protocols and dApps who protect their users the most will win.

Many thanks to Sina, Hasu, Dev Ojha, Walter Smith, and Christine Kim for their conversations and feedback.

Endnotes:

[1] MEV TAM estimates from various data providers.

[1] Chorus One’s data annualized is roughly $921m a year (their data starts from August 2020 and ends at the Merge)

[2] Chorus One further separates the number into good and bad MEV, $713.95M good (arbitrage and liquidations) + $1206.11M bad (sandwiches)

[3] EigenPhi only has data for 2022 and onwards

[4] Flashbot’s does have sandwich data in Dune, unfortunately the data is not particularly clean. However, digging around has yielded numbers that are similar to Chorus One’s topline.

[2] Arbitrage between venues is difficult to minimize without changing the underlying L1/L2 protocol. Some designs include auctioning off access to the first transaction in a block, but that would require a change to the base layer. Though there may be some constructions where if a sufficient percentage of ETH validators restake then there can be an extra protocol auction.

[3] Dev from Osmosis notes how this can be mitigated by enshrining the oracles into the consensus for appchains (forcing ⅓ of the validator set to collude is difficult). Perhaps restaking can be used to mitigate this. Or auction for the right to “submit” the oracle update, and thereby the right to front run / back run it (h/t Sina)

Data

Legal Disclosure:

This document, and the information contained herein, has been provided to you by Galaxy Digital Holdings LP and its affiliates (“Galaxy Digital”) solely for informational purposes. This document may not be reproduced or redistributed in whole or in part, in any format, without the express written approval of Galaxy Digital. Neither the information, nor any opinion contained in this document, constitutes an offer to buy or sell, or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell, any advisory services, securities, futures, options or other financial instruments or to participate in any advisory services or trading strategy. Nothing contained in this document constitutes investment, legal or tax advice or is an endorsementof any of the digital assets or companies mentioned herein. You should make your own investigations and evaluations of the information herein. Any decisions based on information contained in this document are the sole responsibility of the reader. Certain statements in this document reflect Galaxy Digital’s views, estimates, opinions or predictions (which may be based on proprietary models and assumptions, including, in particular, Galaxy Digital’s views on the current and future market for certain digital assets), and there is no guarantee that these views, estimates, opinions or predictions are currently accurate or that they will be ultimately realized. To the extent these assumptions or models are not correct or circumstances change, the actual performance may vary substantially from, and be less than, the estimates included herein. None of Galaxy Digital nor any of its affiliates, shareholders, partners, members, directors, officers, management, employees or representatives makes any representation or warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy or completeness of any of the information or any other information (whether communicated in written or oral form) transmitted or made available to you. Each of the aforementioned parties expressly disclaims any and all liability relating to or resulting from the use of this information. Certain information contained herein (including financial information) has been obtained from published and non-published sources. Such information has not been independently verified by Galaxy Digital and, Galaxy Digital, does not assume responsibility for the accuracy of such information. Affiliates of Galaxy Digital may have owned or may own investments in some of the digital assets and protocols discussed in this document. Except where otherwise indicated, the information in this document is based on matters as they exist as of the date of preparation and not as of any future date, and will not be updated or otherwise revised to reflect information that subsequently becomes available, or circumstances existing or changes occurring after the date hereof. This document provides links to other Websites that we think might be of interest to you. Please note that when you click on one of these links, you may be moving to a provider’s website that is not associated with Galaxy Digital. These linked sites and their providers are not controlled by us, and we are not responsible for the contents or the proper operation of any linked site. The inclusion of any link does not imply our endorsement or our adoption of the statements therein. We encourage you to read the terms of use and privacy statements of these linked sites as their policies may differ from ours. The foregoing does not constitute a “research report” as defined by FINRA Rule 2241 or a “debt research report” as defined by FINRA Rule 2242 and was not prepared by Galaxy Digital Partners LLC. For all inquiries, please email [email protected]. ©Copyright Galaxy Digital Holdings LP 2023. All rights reserved.