Crypto & the Travel Rule

Last week, policymakers at the European Commission proposed applying the travel rule to cryptocurrency transactions. In this report, we explain the history of the travel rule, examine how the rule is implemented in traditional markets, and explore what it means for crypto.

Key Takeaways

As an extension to the FATF’s “travel rule,” the European Commission (EC) proposed new AML/CFT legislation, placing more customer due diligence requirements on virtual asset service providers (VASPs) around recordkeeping and data sharing.

The new EU AML proposals (now scheduled to be finalized in October) apply to the entire crypto sector, expanding beyond the existing scope of the travel rule for covered VASPs, and prohibits “anonymous crypto wallets” serviced by VASPs.

Importantly, the proposed rules apply to the provisioning of anonymous services from VASPs rather than the provisioning of the software for self-custodied wallets. Despite some initial market confusion around the EU’s language, a European Commission spokesperson confirmed that “this requirement does not apply to unhosted wallets.” The rules do not affect P2P transfers or non-custodial wallets.

The Travel Rule

Combatting money laundering is a key focus of financial regulation around the globe. Know-Your-Customer (KYC) regulations in most jurisdictions require that regulated financial services companies collect and store identifying information on their customers, whether individuals or businesses. In June 2019, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), a global financial regulatory standards body, recommended that the “travel rule” be applied to institutions that handle cryptocurrencies.

The travel rule, as implemented in various jurisdictions by law or regulation, requires that regulated institutions include that identifying information with any transfer of funds to another regulated institution. In doing so, institutions (and potentially regulators or law enforcement) can monitor for money laundering or terrorist financing. In the US, the “travel rule” has been in effect since May 28, 1996 when issued by the US Treasury Departments Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) as part of rulemaking to implement the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA).

Ultimately, the travel rule places a recordkeeping and transmission burden on companies, not individuals. This is an important distinction, given that an enormous portion of the cryptocurrency ecosystem operates in a self-custody, P2P basis.

FATF’s Travel Rule Guidance vs. FinCEN’s US Travel Rule

FATF R.16 Travel Rule. The revised guidance for the Travel Rule (Recommendation 16) advises VASPs to share recipient and receiver identifying information for transactions over USD/EUR 1,000. For transfer originators, VASPs under the FATF are to provide: (i) name, (ii) account number, and (iii) address – although this data field can be substituted for other identifying info specified by FATF. For transfer recipients, VASPs are to provide the name and account number.

FinCEN’s US Travel Rule. Compared to R.16, FinCEN’s US Travel Rule places a higher threshold on transfer amounts (>$3,000) and requires money transmitters involved in virtual currencies to provide more identifying information for originators. Originator information must include: (i) name, (ii) account number if available, (iii) address, (iv) identity of the financial institution, (v) transmittal amount, and (vi) execution date. The only hard requirement for recipient information is the identity of the financial institution, but soft requirements include the recipient’s name, account number, and address (when available).

Timeline for Finalized FATF Guidance

FATF indicated it had received many responses to its revised draft guidance on the Travel Rule from March (particularly around impacted entities, unhosted wallets, and potential DeFi regulation) and has extended the guidance deadline to October 2021 to allow a sufficient period for review. The EC, after announcing its package of legislative proposals, clarified that open-source, non-custodial wallets are not prohibited by the new EU AML proposals.

Note: In December 2020, former Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin led an initiative on regulating self-hosted wallets, but this proposal, and all other active agency proposals, was frozen by newly elected President Biden in the following month. FinCEN has not yet proposed new guidelines following that freeze.

Background on the Financial Action Task Force

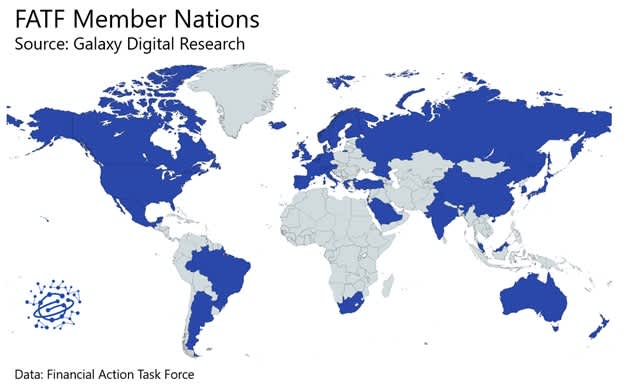

FATF was founded at the 1989 G7 summit in Paris as a financial standards organization focused on creating policies and procedures for economies to prevent money laundering. FATF does not have legal authority – it is a global standard-setting body whose membership is comprised of countries and regional organizations. Member countries send delegates to work on drafting proposals and guidelines for the global economy. Today, FATF has 39 full members, comprised of 37 nation states and 2 regional organizations (the European Commission and the Gulf Cooperation Council). Several other regional anti-money laundering organizations are associate members and can intervene and participate, while 30 other members are observers only (which include organizations like the African Development Bank, Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, the International Monetary Fund, and other groups. FATF’s presidency rotates between member nations every 2 years.

FATF’s mandate is to create recommendations for member states on how to best prevent money laundering. Following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, its mandate was expanded to include preventing terrorist financing. Recommendations from FATF are not binding, but in practice, nations that fail to implement or deviate significantly from its guidelines can find themselves placed on the organization’s “Gray List” or “Black List” and find their access to the international financial ecosystem curtailed.

Status of Travel Rule Implementations

Member states are currently evaluating and beginning to require that institutions follow the travel rule for crypto transactions. In its second 12-month review published on July 5, FATF issued a self-assessment questionnaire on the implementation of the previous Travel Rule guidance finalized in 2019 and received 128 responses from jurisdictions (37 nation states, the EC, and 90 FSRB member jurisdictions). Of this amount, only 58 jurisdictions (~45%) reported introducing the necessary legislation to regulate VASPs and 26 jurisdictions (~20%) were in the process of doing so; the remaining 38 respondents (~34%) had either not yet commenced the necessary regulatory process or were still undecided on their approaches to VASPs.

With most jurisdictions not yet implementing the Travel Rule standards, FATF concluded a concerning level of safety gaps and urged the remaining jurisdictions to adopt the necessary legislations as quickly as possible. Other findings from the review highlighted progress the private sector made along investing in the necessary compliance solutions and suggested implementation at the jurisdiction-level could incentivize further private sector adoption.

The US, Switzerland, and Singapore are among countries that have implemented the Travel Rule. Members from 30 impacted entities, including most of the major crypto exchanges, formed the US Travel Rule Working Group for a coordinated approach to compliance with the Travel Rule. The co-chairman of the Singapore Blockchain Association, Chia Hock Lai, acknowledged the progress that the US has made through its working group, but suggested that Asia may ultimately lead in the implementing the travel rule compliance standards.

The EC is pushing for a harmonized approach for consistent supervision across all member countries and intends to create a new EU AML Authority (AMLA).

Evaluating the Effects of the Travel Rule

Requiring that the travel rule be applied to VASPs has several positive and negative effects.

Positives

Can potentially help businesses thwart criminal use, provide authorities with faster access to information and speed up investigations and recovery of misused assets

Brings crypto into the same regulatory regime as traditional financial services, perhaps making it easier for crypto to go mainstream

Ensures law enforcement has data to request in case of criminal investigations

Creates a stronger legal and compliance framework that could provide industry participants with more trust in the digital asset ecosystem and support industry development

Negatives

Creates additional financial surveillance, increasing risk of PII data loss or misuse

Potential nefarious VASPs could attempt to steal PII data, or could lose the data in data breaches, which are somewhat common

Requires users to place trust in VASPs when sharing PII

Increases likelihood of government surveillance

Confusing to apply to crypto, burdensome to implement

High compliance costs can have outsized impact on smaller VASPs, limiting industry competition

Conclusion

FATF’s guidelines are important because, over longer time frames, they tend to become enacted as law or regulation in most of the world’s advanced economies. However, member nations don’t implement FATF guidelines quickly, and how they are implemented varies across jurisdictions. While there are other issues under consideration by FATF, including how to handle decentralized exchanges and multi-signature wallets, the travel rule is the most likely to have any practical implications in the near term, as several jurisdictions are already in process of implementing it.

The application of the travel rule to crypto companies (VASPs) is inevitable as crypto becomes more integrated into the global financial system. Bringing crypto companies into compliance with rules widely applied to mainstream financial service companies is ultimately a sign of the emerging asset class’s maturity and signals that crypto is here to stay.

Notably, the travel rule cannot be implemented perfectly without prohibiting users from withdrawing to unknown cryptocurrency addresses. Cryptocurrency networks, unlike traditional financial accounts, operate using pseudonymous addresses, even where the funds tied to those addresses may be custodied by institutions. Unless VASPs prohibit the withdrawal of funds to unknown addresses, the application of the travel rule will never be comprehensive if VASPs allow users to enter an unknown cryptocurrency address as a recipient. To ensure that 100% of VASP-to-VASP transfers comply with the travel rule, regulators would probably need to prohibit the ability of VASP customers to withdrawal to addresses unknown to the VASP.

However, if regulators did prohibit the withdrawal of funds to unknown addresses, that would represent a major attack against the core of crypto because it would make it impossible for regulated institutions to serve as onramps into a growing decentralized ecosystem where P2P transactions are essential.

To be clear, no such prohibition has been proposed by FATF or national regulators, which is key. As proposed and implemented, travel rule guidelines simply impose new recordkeeping burdens on institutions, like crypto exchanges, that are already regulated. For its part, the cryptocurrency industry has not settled on a technology solution or business process to comply with the travel rule, though several solutions have been proposed.

Legal Disclosure:

This document, and the information contained herein, has been provided to you by Galaxy Digital Holdings LP and its affiliates (“Galaxy Digital”) solely for informational purposes. This document may not be reproduced or redistributed in whole or in part, in any format, without the express written approval of Galaxy Digital. Neither the information, nor any opinion contained in this document, constitutes an offer to buy or sell, or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell, any advisory services, securities, futures, options or other financial instruments or to participate in any advisory services or trading strategy. Nothing contained in this document constitutes investment, legal or tax advice or is an endorsement of any of the stablecoins mentioned herein. You should make your own investigations and evaluations of the information herein. Any decisions based on information contained in this document are the sole responsibility of the reader. Certain statements in this document reflect Galaxy Digital’s views, estimates, opinions or predictions (which may be based on proprietary models and assumptions, including, in particular, Galaxy Digital’s views on the current and future market for certain digital assets), and there is no guarantee that these views, estimates, opinions or predictions are currently accurate or that they will be ultimately realized. To the extent these assumptions or models are not correct or circumstances change, the actual performance may vary substantially from, and be less than, the estimates included herein. None of Galaxy Digital nor any of its affiliates, shareholders, partners, members, directors, officers, management, employees or representatives makes any representation or warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy or completeness of any of the information or any other information (whether communicated in written or oral form) transmitted or made available to you. Each of the aforementioned parties expressly disclaims any and all liability relating to or resulting from the use of this information. Certain information contained herein (including financial information) has been obtained from published and non-published sources. Such information has not been independently verified by Galaxy Digital and, Galaxy Digital, does not assume responsibility for the accuracy of such information. Affiliates of Galaxy Digital may have owned or may own investments in some of the digital assets and protocols discussed in this document. Except where otherwise indicated, the information in this document is based on matters as they exist as of the date of preparation and not as of any future date, and will not be updated or otherwise revised to reflect information that subsequently becomes available, or circumstances existing or changes occurring after the date hereof. This document provides links to other Websites that we think might be of interest to you. Please note that when you click on one of these links, you may be moving to a provider’s website that is not associated with Galaxy Digital. These linked sites and their providers are not controlled by us, and we are not responsible for the contents or the proper operation of any linked site. The inclusion of any link does not imply our endorsement or our adoption of the statements therein. We encourage you to read the terms of use and privacy statements of these linked sites as their policies may differ from ours. The foregoing does not constitute a “research report” as defined by FINRA Rule 2241 or a “debt research report” as defined by FINRA Rule 2242 and was not prepared by Galaxy Digital Partners LLC. For all inquiries, please email contact@galaxydigital.io. ©Copyright Galaxy Digital Holdings LP 2022. All rights reserved.