Introduction

Decentralization is one of the most compelling narratives driving crypto adoption today. It is core to the value proposition of protocols like Bitcoin and Ethereum, as well as the applications that are built on top of them. There are many ways to measure and describe decentralization, but at the core of the concept is the notion that power is distributed from the center to the edges of a system. But organizing for collective action when power is dispersed is a problem that humans have faced for thousands of years. Achieving consensus on the proper role of power, changes to law, or the governance mechanisms themselves is extremely difficult in decentralized systems, including pure democracies.

The creation of public blockchains, which are decentralized systems of varying degrees, has necessitated the creation of new mechanisms to achieve consensus on governance decisions, including how or when to upgrade the system, how to manage the system’s resources (including money), and how to modify governance parameters themselves. The emergence of decentralized applications built atop these systems, particularly those that provide decentralized finance (DeFi) uses, and the decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) that have been formed to govern them, has created a new design space for experimenting in governance. (For a high level overview of DAOs, read this whitepaper from Galaxy Research.)

A system can only be as decentralized as its weakest link—that is, if one aspect is highly decentralized but another important one is not, it is difficult to consider the system truly decentralized as a whole. Governance, therefore, is a critical component that can directly dictate a system’s level of decentralization. If a network’s nodes are decentralized, but its code development and upgrades are not, the system may lack sufficient decentralization. Governance in crypto today takes many forms, each of which has its own trade-offs. More adaptable governance structures may achieve adaptability and innovation at the expense of resilience and decentralization, while inflexible systems may be difficult to improve.

While there are several ways to view decentralization and governance for a base-layer blockchain, such as Bitcoin or Ethereum, this paper focuses on the current governance mechanisms and issues with decentralized applications in the finance vertical. In Decentralized Finance (DeFi), governance is necessary to ensure that projects truly are decentralized financial applications, not just financial applications that happen to rely on a blockchain. Failure to understand the underlying governance dynamics that dictate decision-making within the application or protocol can lead uninformed users to believe they have an input in a system that they really do not. At the extreme, this can lead to users getting their funds confiscated as seen in Beanstalk Farms or face forced liquidation as seen on Solend.

Given the nascent nature of blockchain and decentralized application design, governance will play an increasingly important role in ensuring protocols can meet the demands of an ever-changing space. Good governance enables protocols to effectively respond to change so that they can continue to achieve their objective – itself often a contentious point of debate – while minimizing the work required on the part of the community to enact these changes.

This report outlines governance design mechanisms for leading Ethereum DeFi applications to better understand the makeup of the DeFi governance ecosystem and its future direction.

DeFi Governance Mechanisms

Governance Token

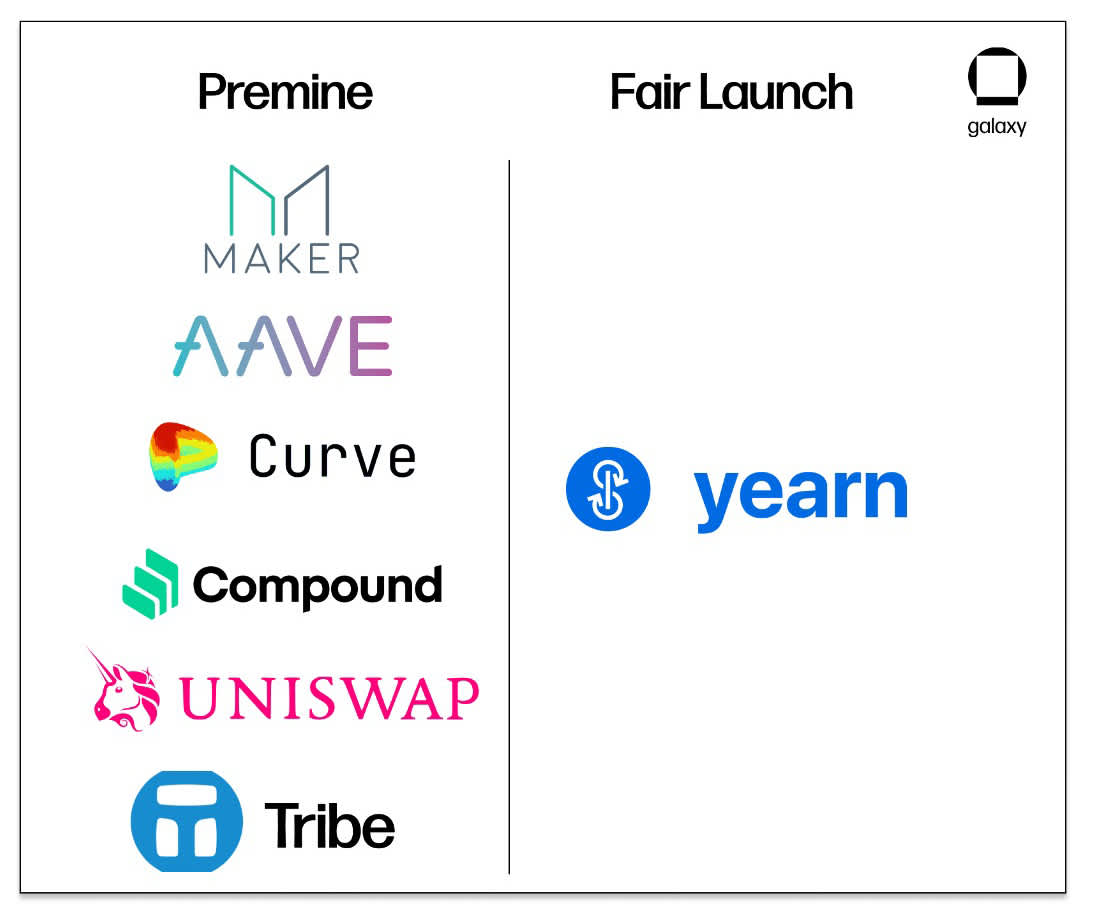

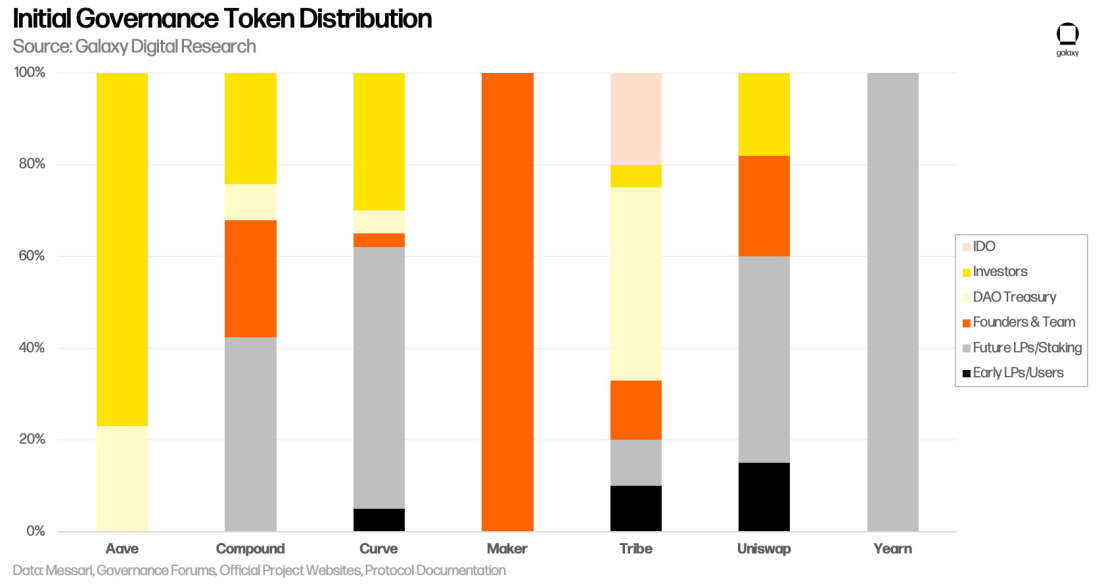

DeFi protocols primarily rely on governance tokens as a means of transferring agency from centralized teams to protocol participants. In most cases, governance tokens are initially distributed to project founders and developers, investors, and early contributors and users. The allocations of initial distributions can take many forms, ranging from “fair launch” to heavily “pre-mined.” `

Fair Launch. This type of distribution method provides equal chance at token allocation to all members of the public, reserving no allocation for developers, foundations, or investors. While tokens are not set aside for latecomers, these launches are announced publicly, open to all who are aware, and typically do not require any type of special access or knowledge. For example, Bitcoin had a fair launch because Satoshi Nakamoto announced the creation of the project publicly (on the cryptography mailing list), mined the first block with a proof-of-timestamp (“The Times 03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks” to prove that the block wasn’t mined earlier than stated, and then released the software publicly so all others could participate. Whether through mining, staking, faucets, or other mechanisms to claim tokens, fair launches do not guarantee equal outcomes, merely equal opportunity. DeFi examples: Yearn.finance (YFI).

Pre-mine. Projects with a “pre-mine” or “genesis allocation” launch with tokens allocated to a set of initial stakeholders that often include early investors, team members, and a non-profit foundation or DAO created to provide ongoing support or grants to the ecosystem. Tokens are also either distributed to the public via direct methods (airdrops) or indirect methods (staking). This distribution method has a wide variety of implementations, but the concept typically stems from perceived shortcomings of fair launches in providing long-term financial support for the ongoing development of the protocol. DeFi examples: Aave (AAVE), Compound (COMP), MakerDAO (MKR), etc.

Holders of governance tokens can typically vote on new proposals for modifications or upgrades to the blockchain or the application, or they can delegate their votes to third parties to vote on their behalf.

Informal Governance

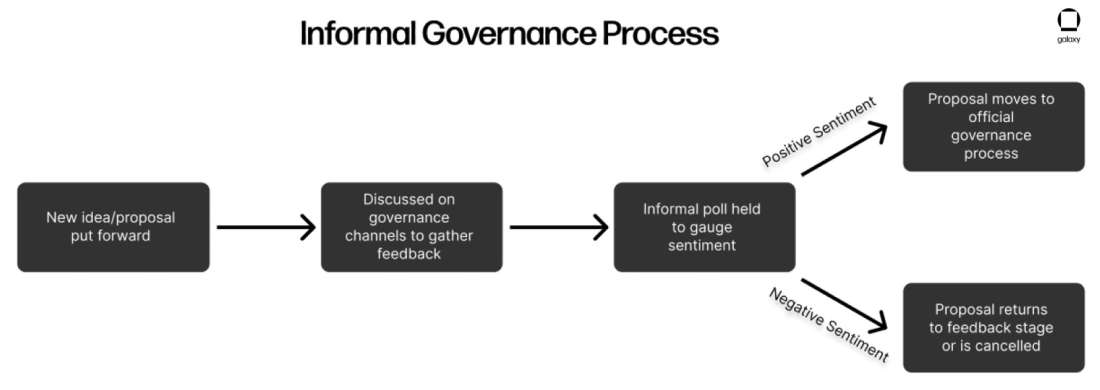

To initiate a change to a project, a participant must submit a governance proposal outlining changes, advantages and disadvantages, and methods for implementation. Before formal proposals are put forward, they are discussed informally in a project’s official forums, Discord, Telegram, and other social mediums. This is often called the “signaling stage,” and it is the primary method through which community brainstorming and iteration on new ideas is conducted.

The signaling stage typically looks something like this:

A new idea for a project modification is put forward by a community member on the social platform. The idea is discussed, and feedback is incorporated.

The updated proposal is posted on the official project governance forum for further dissemination and review. As part of the post, the proposer may include an informal poll to better quantify community enthusiasm.

A rough consensus is reached, and the updated proposal moves forward for an official on-chain or off-chain vote.

Governance Voting: Off-chain vs. On-Chain

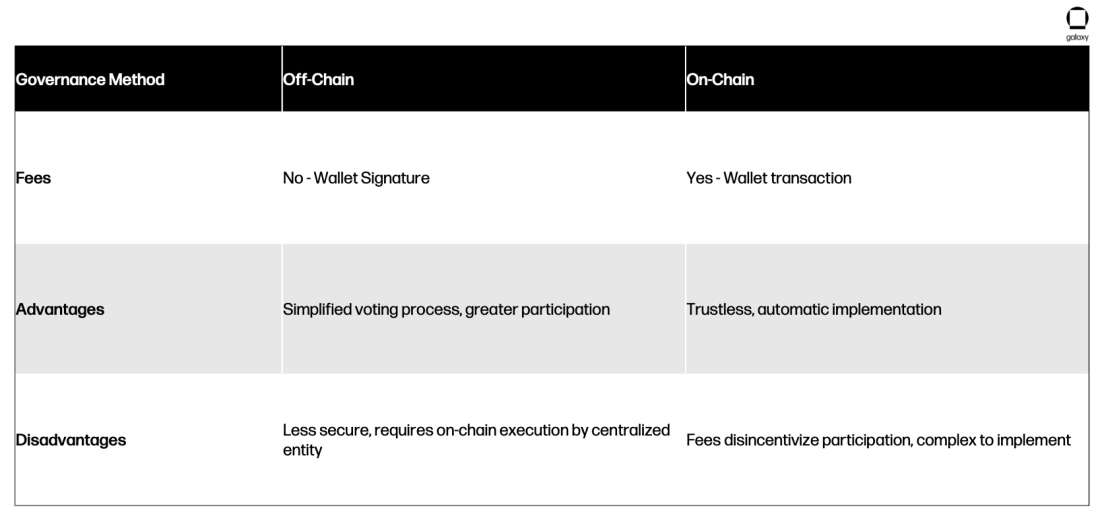

Once a proposal has passed the informal governance stage, it then proceeds to a formal voting process that can implemented on-chain, off-chain, or through a hybrid model.

Off-Chain governance. Off-chain voting primarily relies on voters to sign a message using their wallet indicating their voting preference. The advantage of this approach is that it does not require users to pay a transaction fee to vote (as no on-chain transaction is being processed) and it can simplify the voting process enabling greater participation. The disadvantage is that off-chain votes may not be stored in on the decentralized ledger and are not binding, as on-chain execution by a centralized entity (either the team or a multisig holder) may be required to implement the vote results. One popular off-chain voting application today is called Snapshot – which leverages IPFS, a decentralized storage system, to keep records of voting results.

On-Chain. On-chain voting requires voters to submit a transaction that is then recorded on the blockchain. The primary advantage of on-chain voting is that it is immutable and trustless. If the governance contract is advanced enough, it can also use a governance smart contract to enable automatic implementation of updates once approved, removing the need for any trusted third party. On-chain voting can be complex because it requires smart contracts that can automatically update a protocol according to the vote. It can also be expensive for voters, as users must pay a network transaction fee to vote, which can disincentivize broader participation. Furthermore, it may be more difficult for tokens held in offline cold-storage to participate in on-chain governance. To mitigate participation concerns, some protocols enable users to delegate their votes to others. Compound and Maker have been pioneers in developing on-chain voting solutions, with Compound’s open-source Governor Bravo smart contract solution widely used in other applications.

Common voting requirements include parameters like:

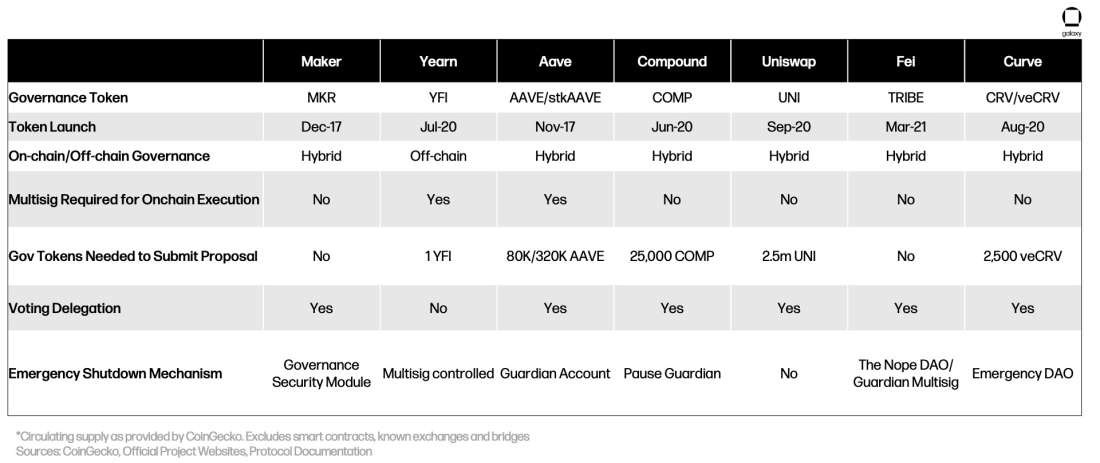

Overview of Governance in DeFi Protocols

MakerDAO

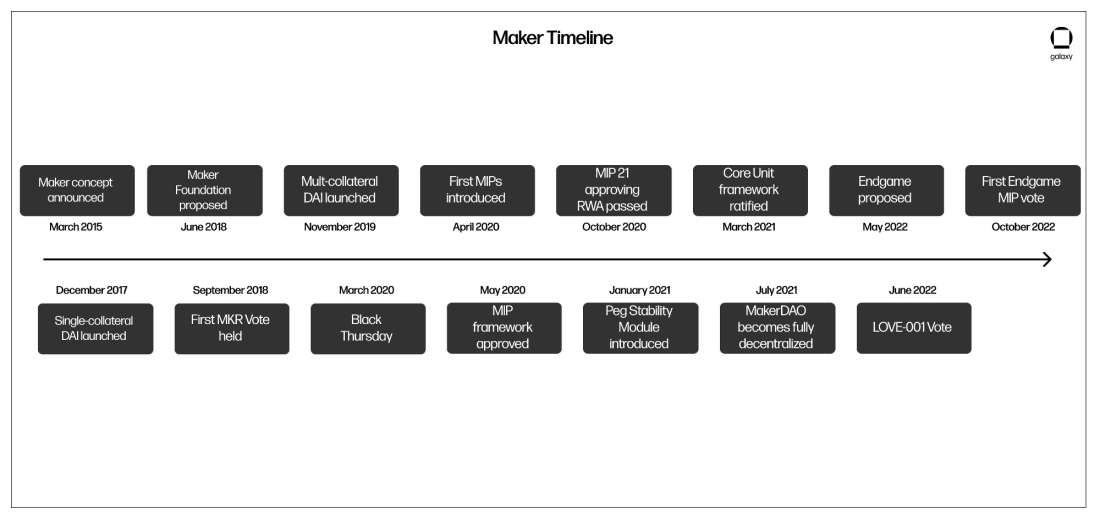

MakerDAO is a decentralized, over-collateralized stablecoin issuance platform and is one of the oldest decentralized DeFi applications in the crypto ecosystem. Users can deposit crypto collateral to borrow Maker’s decentralized stablecoin DAI. The protocol was founded in late 2014 by Rune Christensen and has since undergone significant governance transitions.

Founded as a DAO, the Maker governance process has always been determined by holders of Maker’s governance token – MKR – voting on new proposals. Today, Maker is completely governed by its DAO, but from 2018 to 2021 Maker development was guided by the Maker Foundation, an entity established to bootstrap the protocol and develop a path toward fully decentralized governance.

All MKR was initially held by the project’s founders and distributed ad-hoc to contributors and early investors. To bootstrap funds for the protocol’s development, $54.5 million MKR tokens were sold directly to investors during three private sales from 2017-2019, representing 15.5% of MKR’s total outstanding supply. While MKR holders were able to vote on specific proposals outlining the future vision of Maker during this time, the direction was largely set by Rune and core contributors to the Foundation, many of whom were previous contributors to the DAO.

Critically, the Maker Foundation set the core principles (a constitution of sorts) to guide future governance of Maker and put in place the infrastructure needed for the Maker protocol to operate DAI and run decentralized governance. In 2021, the Maker Foundation dissolved and all MKR tokens held in the MKR development wallet were handed over to a community wallet governed by the DAO.

Overall, Maker has one of the most complex governance processes of any DeFi protocol, and the process itself has undergone significant iteration over the years. In addition for being known as a core DeFi protocol, Maker’s advanced and specialized governance mechanisms stand out across the ecosystem.

Maker Governance

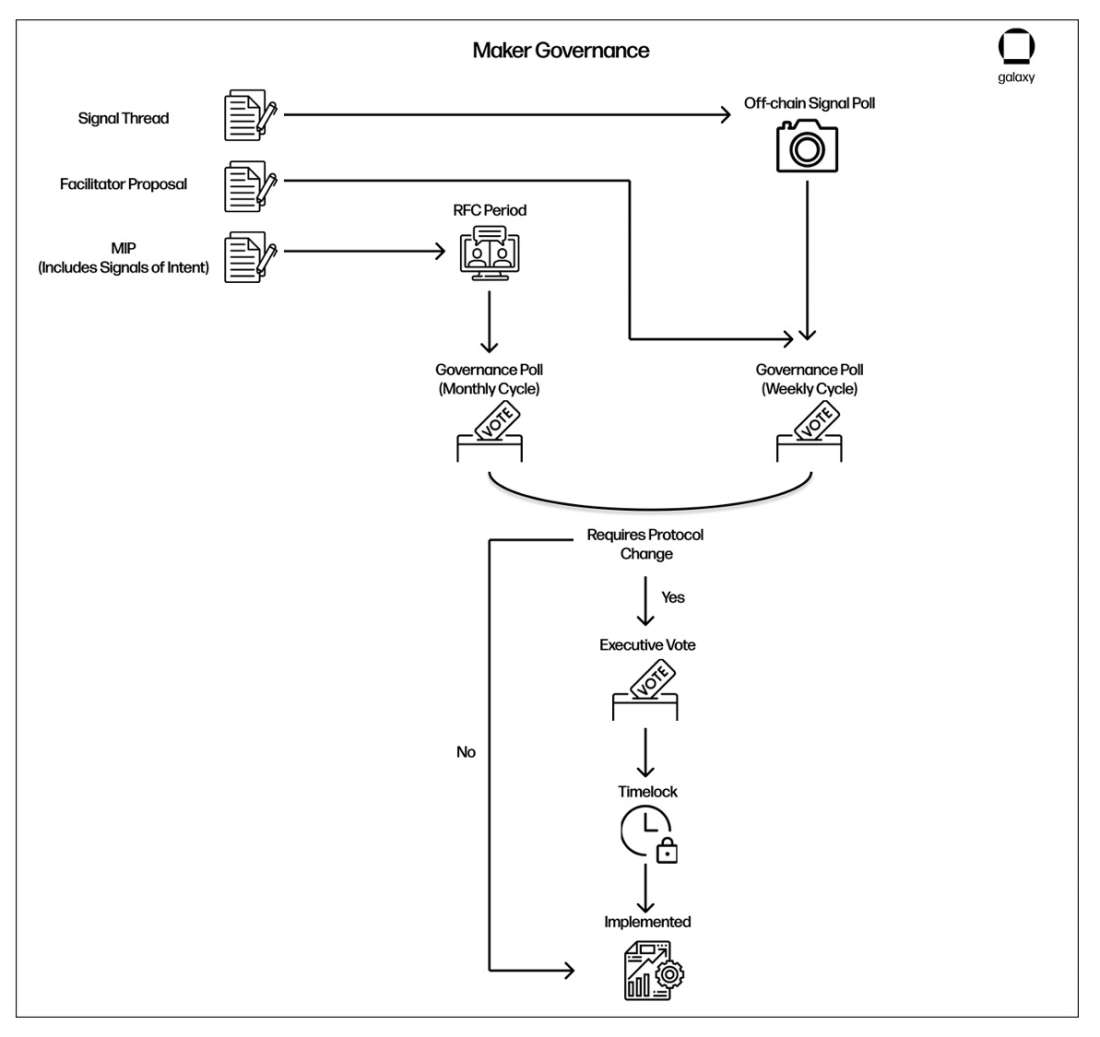

Today, Maker relies on a hybrid of off-chain and on-chain governance mechanisms to update the protocol. Depending on the urgency and scope of the update, new proposals are surfaced through Signal Requests, Declarations of Intent, or Maker Improvement Proposals (MIPs).

Signal Requests

Signal requests have the shortest turnaround time and are used to update existing parameters within the Maker protocol. Discussion begins off-chain through informal governance in what Maker called Forum Signal Threads on the Maker forum. Any member of the community can post a signal thread to gauge community sentiment around a new idea or fix to existing problems.

If there is enough interest in a signal thread (although no specific parameters exist to deem what exactly that means beyond the forum poll having greater than 50% in favor), the proposer can submit it to Maker’s on-chain governance system beginning with a Governance Poll. Proposals submitted to Maker’s governance poll are vetted by Maker’s Governance Facilitators who determine whether to advance them to an on-chain vote.

Governance Facilitators play an important role in the Maker governance process because they act as gatekeepers for advancing new proposals. To prevent them from abusing their power, Governance Facilitators are elected by MKR holders through a Governance Poll and can be removed by the community if they do not uphold Maker’s GovAlpha Mandate, a set of principles to guide individuals involved in the governance process such as neutrality and effective communication. During a governance poll, MKR holders can vote yes, no, or abstain. Proposals that receive more yes’ than no’s are passed.

If a proposal involves a change to the state of the Maker protocol (i.e. a change in risk parameters or opening of a new collateral vault) it then advances to an Executive Vote. Executive votes use a Continuous Approval Voting method whereby executive votes are ongoing until a new executive vote that changes the state emerges. For a new executive vote to override the existing state, it must attract more votes from the current executive vote – i.e., current voters must actively move their vote from the current executive vote to a new one.

Declarations of Intent

Declarations of Intent demonstrate agreement within the Maker community on its intent to update a specific aspect of the Maker protocol. They differ from Maker Improvement Proposals (MIPs) in that they can simply demonstrate an intent without specifying exactly how that intent will be executed, and they differ from Signal Requests because they indicate an intent for the future direction of the broader Maker protocol rather than an update to a specific parameter. Declarations of Intent were added to the Maker governance protocol to solve for a recurring issue in which community members recognized problems with the protocol, discussed the problem, hosted an informal vote to determine whether something needed to be done, and then stopped there. By creating Declarations of Intent, community members have a centralized repository where they can identify what aspects of the protocol require updates.

Maker Improvement Proposal

Unlike Signal Requests and Declarations of Intent, MIPs are permanent changes to the technical aspects of how Maker smart contracts work or the protocol is governed. They follow a similar process as outlined above, however; they take a considerably longer time to advance through the full governance process as the magnitude of changes are much greater.

Core Units

While Maker Governance sets the rules for the Maker protocol, execution is carried out through Maker’s Core Units. Core units are groups of Maker contributors that focus on specific aspects of the Maker protocol ranging from governance to risk management to onboarding of new assets. To create a core unit, Maker community members must make a proposal which must advance through the governance process before being approved. During this process, MKR holders set the core unit’s mandate and budget. After a core unit is formed, Maker holders can also submit proposals to remove core units.

Core units play a critical role in advancing Maker objectives but are still beholden to MKR holders. Proponents argue Core Units are necessary for Maker to operate efficiently, innovate, and execute highly complex financial underwriting in areas like Real World Assets (RWA). Maker’s Sustainable Ecosystem Scaling core unit, for example, serves as an incubator for new contributors to Maker that want to propose a core unit but first need to build the credibility and experience to get it approved.

Critics of Core Units view them as centralized units of power that lack transparency and oversight. As the number of Maker core units has grown (from seven core units at launch to twenty today), it has become increasingly difficult for MKR holders to monitor them, devise and track KPIs, and evaluate their overall performance relative to what they deliver. The introduction of Real World Assets (RWA) – where Core Units interface with non-crypto entities – has also raised significant concerns over the potential for misaligned incentives and an inability for MKR holders to have proper oversight.

Flash Loan Vulnerability

In October 2020, BProtocol – a DeFi liquidation protocol – exploited a vulnerability in the Maker governance system to push forward a proposal giving the protocol whitelist access to Maker’s price oracle. BProtocol took out a flash loan – a loan that allows users to take out a loan uncollateralized as long as it is returned nearly instantly in the same block – of 13,000 MKR on dYdX and instantly deposited it in MKR’s governance contract to vote on the relevant executive vote. This increased the number of votes in the executive vote to a majority, following which the vote was immediately passed and moved to the implementation stage, enabling Bprotocol to retrieve the borrowed MKR tokens repay the flash loan.

Maker has a 12-hour timelock following the approval of any proposal to provide time for the community to intervene, however, MKR holders did not react fast enough leading to the proposal being automatically executed on-chain.

While the perpetrator’s intent was not malicious – BProtocol was transparent about their actions and intentions immediately afterwards – the event highlighted a key vulnerability to the Maker governance process where users could leverage flash loans to form a superficial majority and get their proposal approved. Additionally, the attack highlighted an opportunity for parties with no vested interest in the Maker protocol–i.e. they hold no governance tokens–to influence governance at no cost to themselves.

Despite the setback, the Maker community responded quickly, putting forward a new proposal to increase the timelock form 12 – 72 hours in order to give the Maker community more time to respond and veto a similar event. While flash loan governance attacks are now increasingly difficult, it is still possible for individuals to borrow governance tokens or incentivize holders to achieve their objective.

Endgame

Maker has built one of the most comprehensive and complex governance protocols in the DeFi ecosystem. Iteration over the years, however, has resulted in the creation of a bureaucratic and political governance process that is difficult to understand for both new and established MKR holders. Voting is primarily decided by large token holders creating a plutocracy and disincentivizing meaningful participation from all but the most engaged retail users. Based on analysis by a member of Maker’s Strategic Finance Team core unit in July of this year, it would only take three entities to dictate what does and does not pass Maker’s governance process.

Maker’s Core Unit framework has been effective at ensuring that the protocol maintains a paid and incentivized workforce, but it has also created an opaque organizational structure difficult for the average MKR holder to understand or oversee. However, Maker’s governance process has also helped the protocol to grow, adapt, and weather a highly volatile market environment–during the recent crypto market downturn Maker returned to its position as the number one DeFi protocol by TVL. The governance mechanism itself is highly customizable and adaptable, which can lead to lengthy timelines from proposal inception to execution but has enabled time for proper vetting of and iteration on critical improvements to the protocol such as the Peg Stability Module (central to DAI’s stability).

Looking forward, Maker faces a daunting challenge: it must reduce the complexity of the protocol’s governance to streamline decision making and encourage greater engagement from MKR token holders. Furthermore, the protocol must respond to new regulatory developments, notably the implementation of OFAC sanctions on Tornado Cash, that have heightened concerns over Maker’s exposure to highly centralized collateral like USDC. In recent months, Rune–who had remained relatively removed from governance since the dissolution of the foundation–has become more active and put forward his own vision for the future of Maker governance entitled The Endgame Plan.

As articulated in the most recent iteration of the plan, Endgame’s core underlying motive is to, “make DAI as “bitcoin-like” as possible.” The full extent of changes proposed are beyond the scope of this piece, but it involves significant restructuring of Maker’s current governance design through the creation of MetaDAOs. MetaDAOs are subDAOs in the Maker protocol that have their own tokens and can pursue innovative ideas while reducing the complexity of the core Maker protocol. Maker as it exists today would be consolidated into a simplified protocol called “Maker Core,” that supports the MetaDAOs. Maker Core would provide MetaDAOs with the basic resources needed to launch and support their initiatives, benefiting from their success through tokenomics and yield farming strategies, while limiting it exposure to the risks that may emerge as a result of their activities. Endgame also proposes a radical departure from Maker’s current collateral model by prioritizing the accumulation of ETH/staked ETH as the protocol’s primary reserves backing the value of DAI and launching EtherDAI, a synthetic ETH backed by decentralized collateral.

The implementation of Endgame, however, is a hotly debated topic that must be approved through Maker’s existing governance processes. Competing proposals have been put forth, such as one from Hasu that proposes the creation of a Council of Elders responsible for setting Maker strategy and removing unnecessary decision making from MKR holders. Additionally, a number of core contributors to Maker have published lengthy overviews calling for significant edits to the plan-such as this one by Maker's former Governance Facilitator LongForWisdom and this one by early Maker investor a16z. Primarily, opponents believe Endgame will further increase (not reduce) Maker’s governance complexity and increase the protocol’s financial risk. This could undermine Maker’s core value propositions as they exist today and result in Maker’s end, rather than its Endgame.

As of the writing of this piece, a ratification poll has just passed that will implement the “Endgame Prelaunch,” a series of MIPs that include the formation of initial MetaDAOs, launching some ETH/staked ETH accumulation strategies, and restructuring current Maker governance processes in conflict with Endgame. While the proposal had the needed support and momentum to pass, it is just an initial step in a multi-year governance transition and there is no formal timeline for when the specific MIPs contained in Endgame Prelaunch will begin to be rolled out. Many of them will require new governance polls and/or executive votes before they are fully implemented and may even change depending on feedback from the community as they are fleshed out.

The incredible complexity of Endgame proposal means that only a small majority of MKR token holders truly understand its full ramifications. It is also unclear whether such an ambitious change in the fundamental design of the protocol’s governance would be possible if it was not being driven by Rune. He is one of few individuals in the Maker community with both the influence and resources (in the form of MKR tokens) to push this type of restructuring forward. Maker has proven it can incrementally iterate using its existing decentralized governance structure. But completing a wholesale reorganization of the protocol still requires a centralized leader to spearhead it-a criticism that has been voiced by some members of the community.

The existence of Endgame and other competing proposals indicate growing sentiment across the Maker community that governance as it exists is still imperfect. It is still very early in the process, and it could take years before any new status-quo is reached. The mere fact that the Maker community can have these discussions and collectively work towards reaching consensus on a new solution, however, demonstrates a strength of Maker’s existing governance mechanism–its ability to adapt to new realities.

Aave

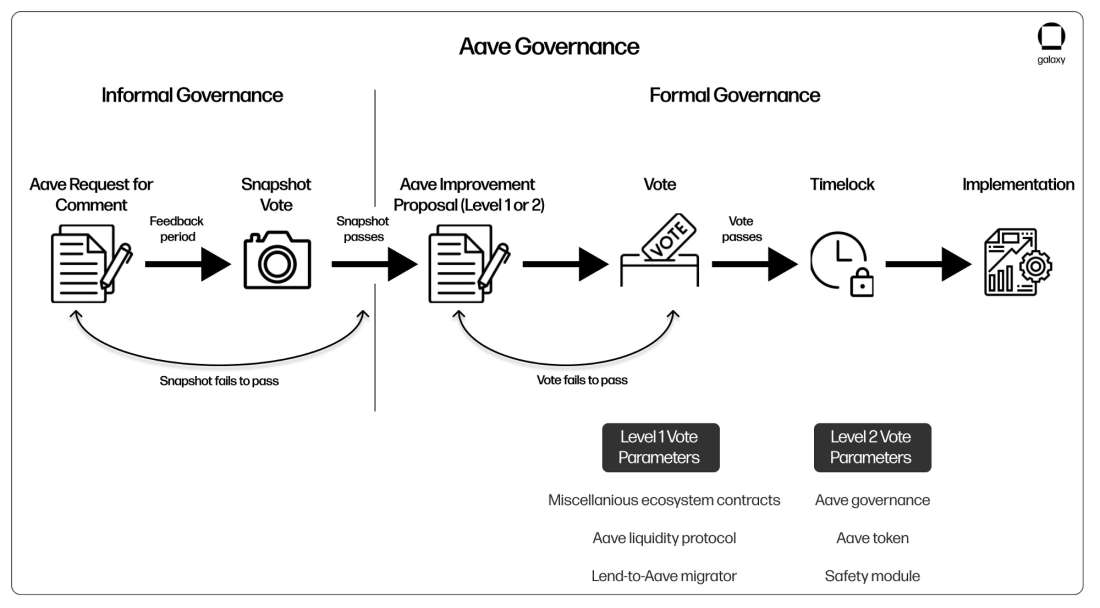

Aave, the number two DeFi protocol by total value locked, has followed a similar governance evolution as Maker. During v1 of Aave’s governance, only Aave genesis team members were able to submit Aave Improvement Proposals (AIPs) to be voted on by the community. In 2020, Aave updated its governance mechanism to enable anyone to make new proposals with its v2 release.

First, Aave holders submit Aave Requests for Comments (ARCs) as part of the informal governance process. Once submitters have solicited and incorporated feedback, proposals are then put to an off-chain vote using Snapshot to ensure a rough consensus has been reached. If a proposal is favorably received, proposers then submit an AIP for an on-chain governance vote using Aave’s governance module.

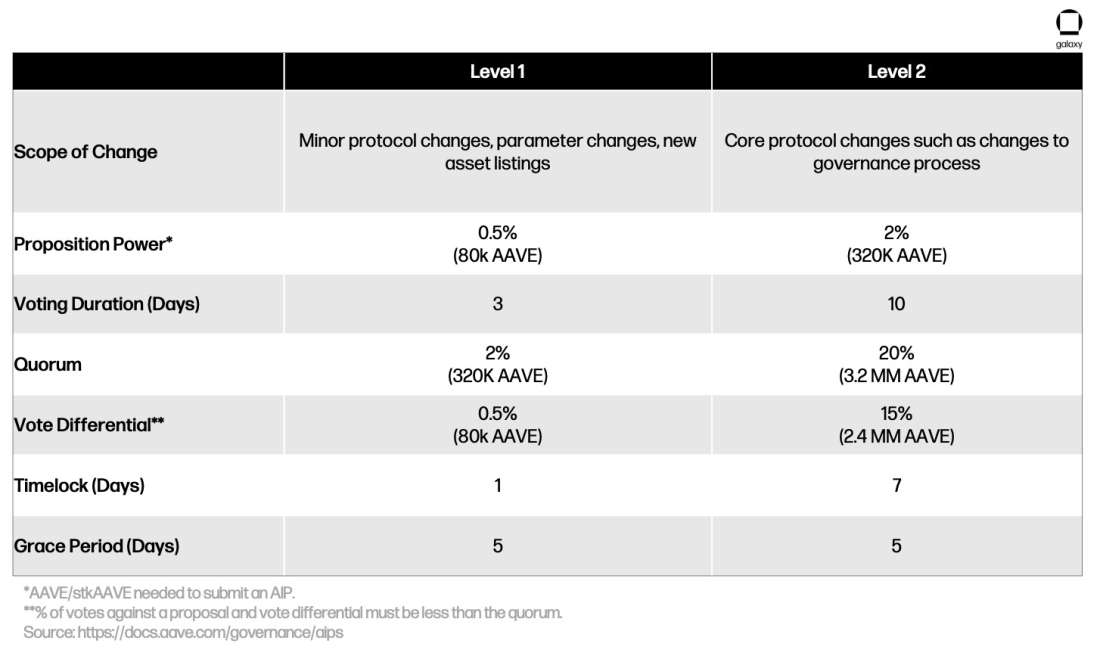

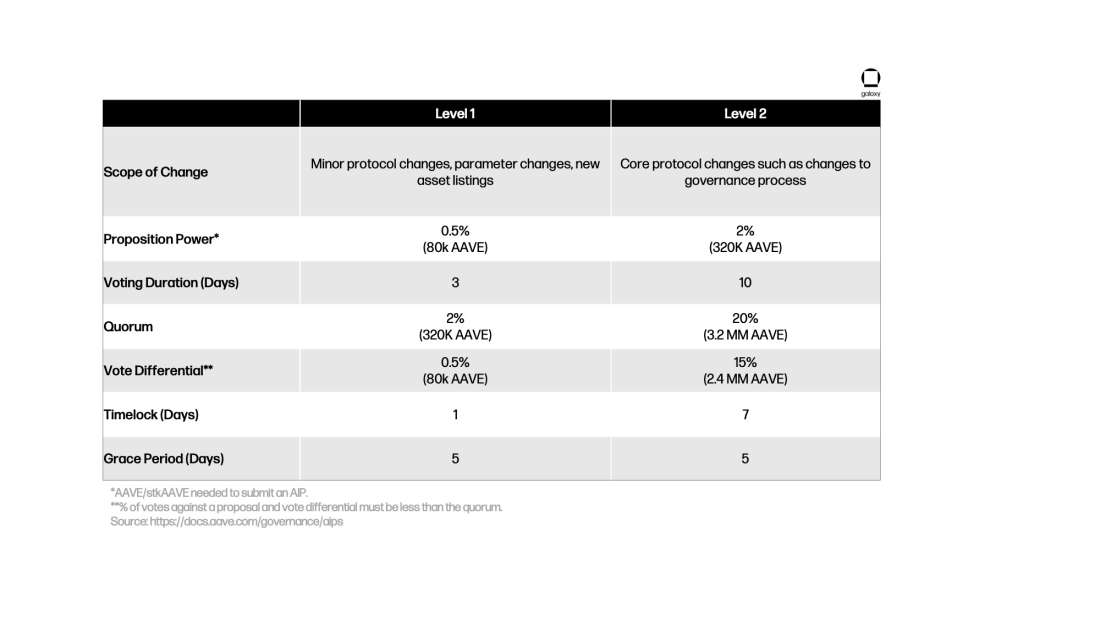

Level 1 vs. Level 2 Permissions

Aave differentiates between proposal types by instituting different requirements for proposals affecting different aspects of the Aave protocol to pass. Proposals impacting the Aave lend/borrow protocol (i.e. updating risk parameters or introducing new collateral types) have a lower threshold for the votes required for it to be approved, the time-lock following vote approval, the duration of voting periods, quorums required, and grace periods. Proposals impacting Aave’s core code (i.e. changes to governance mechanisms) have significantly stricter parameters.

To ensure malicious proposals do not slip through, Aave has also instituted a Guardian Account controlled by a community multisig wallet. Participants in this multisig can intervene and cancel any proposals that are deemed to be an existential threat to Aave’s existence. This differs from Maker’s emergency shutdown method, which requires MKR holders to deposit MKR directly into an Emergency Shutdown Module (ESM).

Outsourcing Model

Aave does not rely on a core unit or constrained delegation model like Maker and Yearn for execution. Instead, work not taken on by the core team is outsourced to third parties. Gauntlet, a financial services and risk management provider for crypto projects runs, Aave’s risk parameters and was recently approved to manage risk for Aave’s new institutional product, Aave ARC. In May 2022, Aave also approved the onboarding of Bored Ghosts Developing (BGD) to implement technical updates and maintenance to the protocol.

Aave Used as a Governance Attack Vectors

The Aave protocol has at times been used as a vector for malicious actors to manipulate other governance votes. In addition to the above-mentioned Maker flash loan governance attack, in April 2022 Beanstalk Farms–a stablecoin protocol–suffered a security breach when a malicious actor took out a $1 billion dollar flash loan in order to approve their own proposal and drain Beanstalk of $80 million. In February 2022, Tron founder Justin Sun also attempted to push through votes on Compound and Maker that would have approved Tron USD–Tron’s stablecoin–for use in borrowing and swapping on those protocols. In that instance, Sun’s actions were identified on the blockchain prior to the votes’ conclusion and both proposals failed to pass as COMP and MKR holders rallied opposition.

Aave itself bears no blame for these actions–protocols need to be wary of the potential for the outstanding supply of their governance token to be bought or borrowed and used to manipulate their governance systems. Projects like Bribe Protocol, for example, offer a means for individuals to incentivize holders of governance tokens to vote in their favor. Instead, it is indicative of the additional difficulties that composable DeFi protocols pose to governance and the need for them to by hypervigilant against unwanted manipulation.

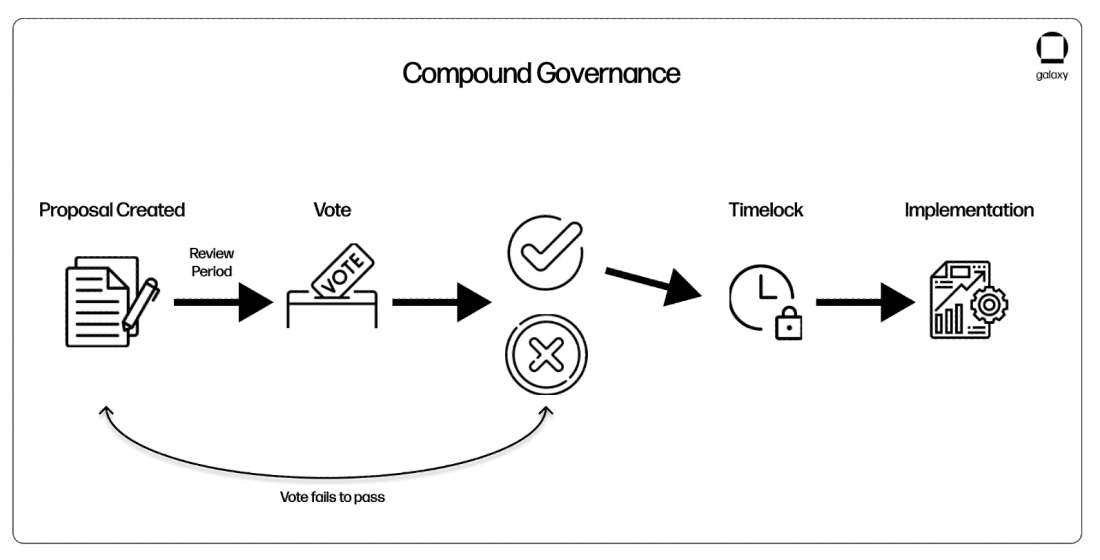

Compound

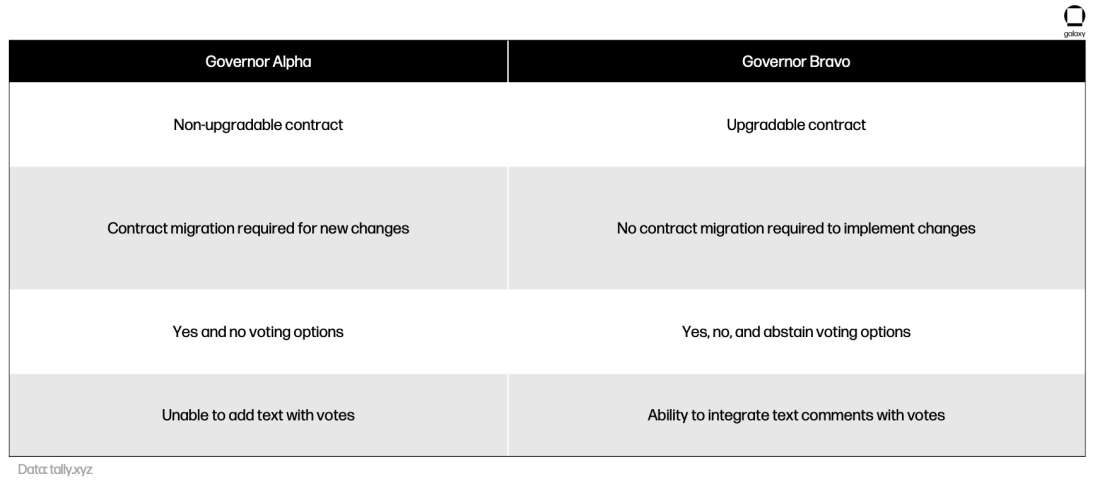

Compound is a lend/borrow protocol on Ethereum that has helped set the standard for simple on-chain governance. In 2020, Compound released its Governor Alpha governance contract, a white label opensource governance smart contract that protocols can use for their own governance process. In March 2021, Compound released Governor Bravo, an updated governance mechanism enabling further customization that is used by Compound today.

Governor Bravo stands out in its simplicity and composability. It has three basic components – the COMP token (Compound’s governance token); the governance module–Governor Bravo–that oversees the trustless implementation and execution of proposals on-chain; and a Timelock that delays the implementation of any new updates by two days to enable users to adapt to the update.

In order to submit a proposal, a user has to have or be delegated 25,000 COMP, after which the proposal undergoes a seven-day governance process resulting in its execution of rejection.

In addition, Compound utilizes a Pause Guardian to enable the Compound community to deal with malicious actions against the protocol. The Pause Guardian can pause supply, borrowing, and liquidations on the compound protocol through a 4 of 6 multisig. Initially controlled by Compound Labs, in August 2021 the Pause Guardian multisig was transferred to a group of active and early Compound contributors from the community who were approved through a DAO vote.

Simple Governance

Compound’s simple and open governance process, however, has also created issues for the protocol. In September 2021, soon after the release of Governor Bravo an exploit was discovered that erroneously deposited nearly $70 million of Compound tokens to COMP holders (~365,000 COMP). The exploit was discovered within hours, but Compound governance had no safeguards in place to revoke the bugged update as the Pause Guardian does not have the power to reverse proposals that have been executed on-chain. The only way to rectify the bug was to pass a new proposal that went through the full governance process – requiring seven days. In the end, Compound was able to recover around ~160,000 of the 365,000 COMP tokens that were mis-allocated due to users voluntarily returning the COMP.

In August, another bug was identified for one of Compound’s ETH price oracles following an update to the protocol. Once again, the fix for the bug required a new proposal to go through Compound’s full governance process and for users affected by the bug to wait seven days for the fix to be implemented. Despite these issues, to this day the Compound community has not updated their governance safeguards to enable newly passed governance votes to be quickly revoked (rather than having to go through another seven-day governance process to revoke them) due to fears of over-centralization of power and Compound’s focus on maintaining a simple and straightforward governance process.

Governor Bravo

Beyond creating a simple framework for Compound’s governance, Governor Bravo has been a boon to the broader crypto ecosystem governance landscape. It offers new protocol founders an easy-to-implement governance mechanism that is battle tested and can be easily integrated with third-party governance voting mechanisms (i.e. Tally) so that protocol users can access votes without the protocol’s development team needing to build their own voting interface. Since creation, OpenZeppelin has built on top of Governor Bravo, adding additional functionality and utility.

UniSwap

Uniswap is the largest aggregated market maker on Ethereum. In September 2020, Uniswap Labs launched its governance token (UNI) and initiated its decentralized governance process. Since then, it has updated to on-chain governance using Compound’s Governor Bravo.

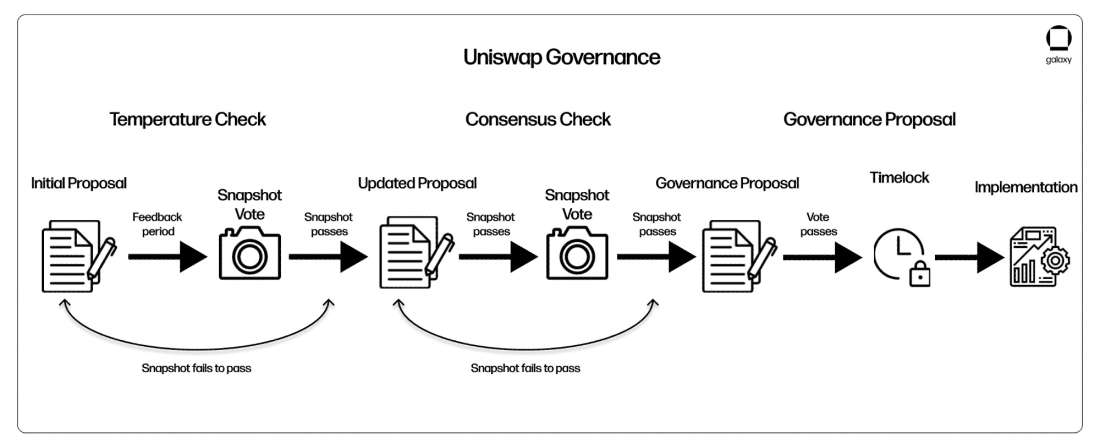

Uniswap proposals must initially go through an informal governance process whereby proposers’ surface new ideas on Uniswap’s official Governance Forum to gauge sentiment and get feedback. Once a proposal has reached informal consensus, proposers must pass a Temperature Check and Consensus Check via Snapshot. Proposers must have at least 1,000 UNI tokens (either delegated to them or self-delegated) to post Temperature and Consensus checks and quorums of 25,000 UNI and 50,000 UNI yes-votes are required respectively in order to be considered valid.

If a proposal passes the temperature and consensus checks, it then moves to Uniswap’s on-chain governance process. The on-chain governance process has the highest quorum requirements: at least 2 million UNI must be delegated to propose an on-chain vote, and a minimum of 40 million UNI must vote yes to pass.

Uniswap governance is limited in its scope, enabling UNI holders to control protocol parameters like fees for specific liquidity pools, the allocation of the Uniswap community treasury, or even the implementation of Uniswap’s Fee Switch (which would divert a portion of Uniswap fees to UNI holders; all fees are currently given to liquidity providers). Otherwise, however, the Uniswap protocol is immutable, meaning the fundamental contracts that facilitate the protocol’s operations are not able to be changed or upgraded. UNI holders do not have the power to pause contracts, reverse trades, or in any other manner alter the behavior of the protocol.

Quorum Requirements

While Uniswap’s governance process appears relatively simple compared to Maker or Aave, its high quorum requirements have made it relatively difficult to implement new changes. The first ever Uniswap governance proposal in October 2020 raised this issue and proposed lowering the quorum requirements for on-chain voting from 40 million to 30 million. Despite 98% of all votes cast approving the update, it was unable to pass as the vote fell short of the 40 million requirement by just over 400,000 UNI. No update to this quorum requirement was ever made due to an increase in the amount of UNI delegated to active voters (which made it more feasible for new proposals to pass). In June 2021, however, the Uniswap community agreed to move forward with a proposal to reduce the submission threshold for submitting on-chain proposals from 10 million UNI to 2.5 million.

To date, only 24 proposals have made it to Uniswap’s on-chain voting stage and of those only 16 have passed and been executed. From one perspective, this points to the success of the Uniswap Labs teams in launching a protocol that meets the needs of its users and is governance minimized. On the other hand, it highlights the difficulties of garnering community consensus and voter engagement in a decentralized governance process. Recognizing this, in January the Uniswap team put forth a new proposal to eliminate the initial requirements of the Temperature Checkphase and turn it into an informal request for comment period, before requiring a new Temperature Check requiring 6 million votes and then the on-chain governance proposal.

Role of Uniswap Team and Uniswap Foundation

The Uniswap Labs team continues to play a critical role in the development and innovation of Uniswap’s core protocol functions. Uniswap Labs has released three versions of the protocol since launch. These updates have been well received by the community as they improve the protocol’s efficiency and customization, but the process by which they are created and released highlights the centralized nature of the protocol’s development and the core role the Uniswap labs team plays in shepherding it.

In August the Uniswap community also approved the creation of the Uniswap Foundation, delegating $74 million in UNI. The Foundation, currently run by two individuals with plans to scale to 12 overtime, has a mandate to help “reinvigorate governance” by funding projects that can reduce governance friction. It will also receive 2.5 million UNI tokens that can either be delegated to individuals who don’t have the required UNI needed to submit new proposals or self-delegated for voting on proposals.

While this should help streamline the process for approving and implementing new proposals that aim to improve governance, it also increases the centralization of the protocol’s governance process by granting a small number of individuals the power to ensure new proposals meet Uniswap’s high quorum requirements. These tokens can be revoked at anytime through a governance vote, providing some protection against their misuse. However, even this could pose is an issue as any such vote it likely to be highly contentious, requiring significant voter engagement and the community reaching a consensus.

Yearn Finance

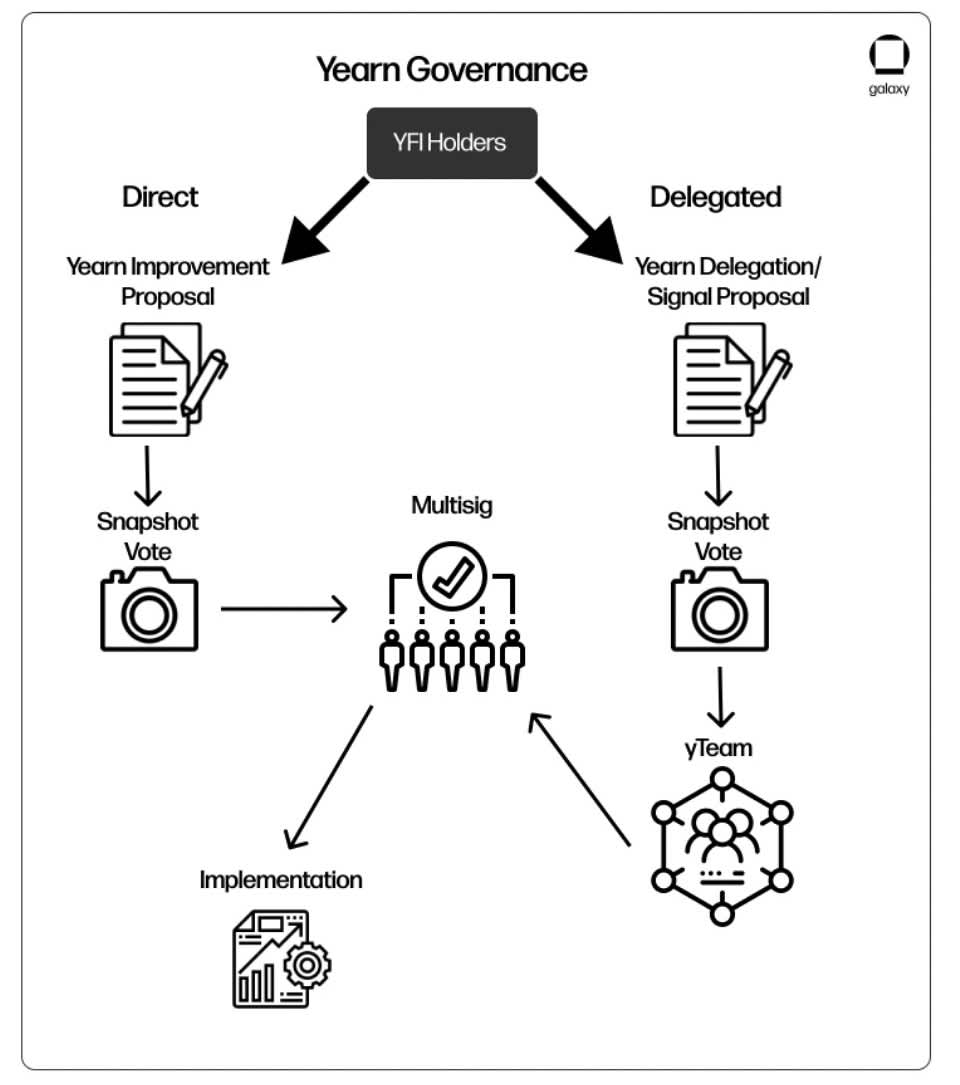

Yearn Finance is a decentralized yield farming platform where users can earn interest on their DeFi tokens. Yearn relies on off-chain voting through Snapshot. Holders of Yearn’s governance token (YFI) wield votes proportionate to the amount of YFI they hold. Anyone can submit a Yearn Improvement Proposal (YIP) to recommend new changes to the protocol. Yearn governance does not have automatic on-chain execution of approved governance proposals and newly approved YIP’s are entirely reliant on the Yearn multisig wallet, which required 6/9 signers, to implement the protocol on-chain.

A month after their launch, and in recognition of the need to accelerate Yearn’s ability to make decisions, YIP 41(Temporarily Empower Multisig) was proposed and passed. As the name suggests, YIP 41 empowered Yearn’s multisig holders to “make personnel & budgetary decisions,” for an initial six-month period. While a centralization of power, YIP 41 was also an important step to enable the protocol’s continued development and growth while a more decentralized governance process was established. Nearing expiration, YIP 41 was extended for an additional three months through YIP-59 while the Yearn community continued to flesh out a more decentralized model.

In April of 2021, Yearn holders voted on YIP-61 to implement Governance 2.0, Yearn’s current governance model. Like Maker, Yearn is an example of a protocol that successfully transitioned from a decentralized governance model to a centralized one, and then back to a decentralized one. This dynamic points to the difficulty of launching a complex DeFi protocol that has a decentralized governance process at inception. Instead, a centralized decision-making team may be required in the early stages of development to create an operational foundation which the decentralized community can then emerge from.

Constrained Delegation

Governance 2.0 introduced the concept of constrained delegation through two new proposal types–Yearn Delegation Proposals (YDP) and Yearn Signaling Proposals (YSP)– and the creation of yTeams, autonomous teams of Yearn contributors empowered with the power to carry out specific responsibilities specified by YFI holders. In this updated framework, YFI holders can submit YDP to create new yTeams or modify the responsibilities of an existing one. YSPs are used to signal community interest or intent for a specific issue. For example, a YSP may be used to demonstrate consensus in community over the addition/removal of a specific member to a yTeam or the need to add a new Yearn vault. If passed, it the relevant yTeam specific to the proposal would be responsible for actually working on and implementing it.

Yearn’s yTeams vs. MakerDAO’s Core Units

Yearn’s model closely resembles Maker’s core unit model, providing token holders with high-level decision-making powers while authorizing individual units of contributors to execute those decisions. Yearn differs from Maker in that the ultimate execution and implementation of updates to Yearn still relies on a multisig to implement them. Going forward, the Yearn community has said that they are working towards moving voting on-chain and getting rid of a centralized multisig to execute implementations.

Despite the similarity of their governance models, Yearn has not suffered from the same political infighting increasingly common in Maker. One possible explanation for this is that Yearn holders are aligned behind Yearn’s future vision and development as an interest earning protocol while there is considerable disagreement amongst Maker holders over the primary objective of the Maker protocol. This has enabled Yearn to leverage the constrained delegation model to streamline its governance process while Maker’s core unit model is increasingly under attack for failing to uphold Maker’s purpose.

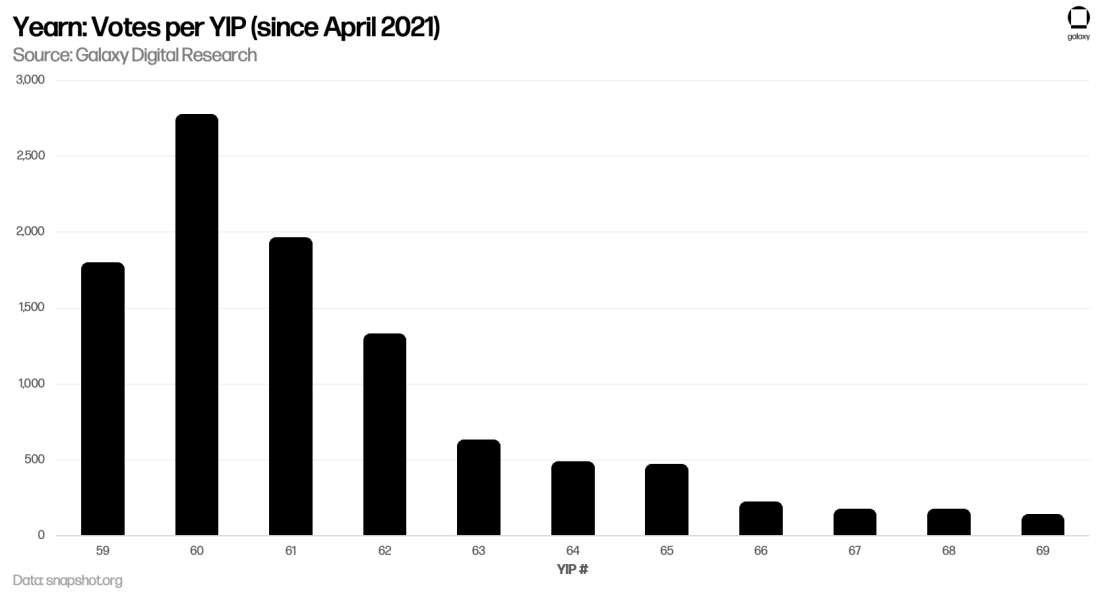

Another explanation is that Maker continues to attract considerable talent interested in further developing and advancing the protocol, which in turn has increased the protocol’s diversity of opinion and made the decision-making process more difficult. Yearn, on the other hand, has seen user growth and TVL decline, and voter apathy appears to be at all-time highs. Lack of friction in the Yearn governance process may be because the protocol lacks a compelling vision driving user engagement and investment in the protocol’s direction. Since peaking in April 2021, total YFI cast and unique voters per proposal have dropped dramatically.

Tribe DAO

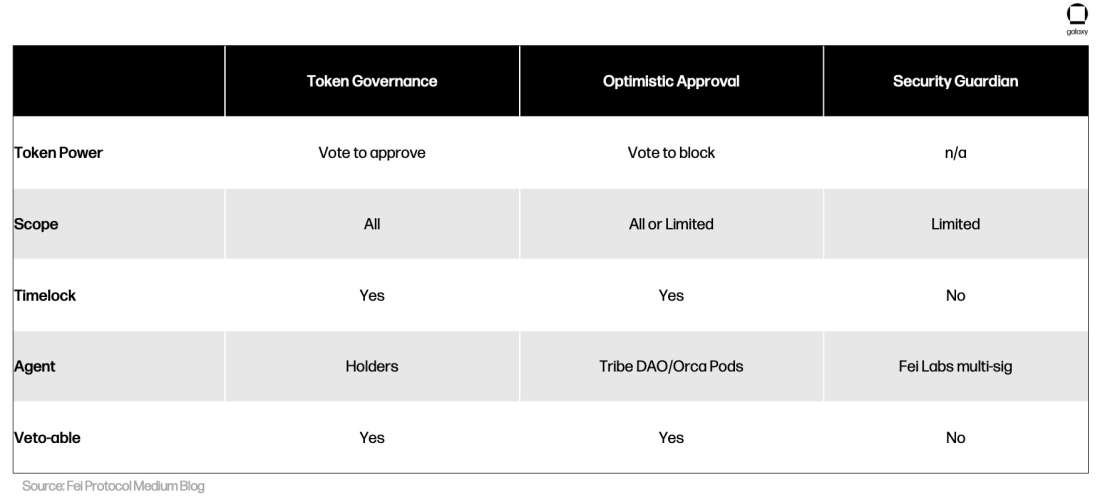

Tribe DAO is a “megaDAO” composed of Fei Protocol, Rari Capital Fuse, Turbo, Volt, and Midas Capital. Initially only overseeing Fei Protocol – a decentralized stablecoin – Tribe has grown as the Fei team has introduced new products and even merged with Rari Capital Fuse. Tribe governance relies on three pillars – token governance; optimistic governance; and Security Guardian.

Token Governance: Token governance in Tribe follows the same principle of one-token-one-vote as described for many of the other protocols in this piece. Holders of Tribe’s governance token can vote for and against new proposals that are put forward by the Tribe community. They also are responsible for electing Tribe’s Tribal Council, a centralized entity that has special permissions to streamline decision making and implement new proposals.

Optimistic Governance: Tribe relies on a process of negative consent to approve new proposals. This is called Optimistic Governance because it assumes that a proposal will be approved unless enough TRIBE holders’ step in to block it. This progressive stance differs significantly from more conservative approaches that require significant quorums and thresholds for acceptance.

Optimistic Governance is implemented through two different groups – Optimistic Pods and The Nope DAO. Optimistic pods resemble Maker’s core units and Yearn’s constrained delegation. Pods are approved by governance token holders and given a specific mandate and budget. At creation, the primary pod is the Tribe Council which has a 5 of 9 multisig and was elected by the Tribe community and essentially operates as a proposal accelerator. New proposals put forward by the Tribe Council pod can be implemented into the protocol more quickly than other proposals. If they are vetoed, however, they must go through a much longer Tribe DAO governance process than standard proposals.

Tribe uses Orca, a DAO tooling provider, to create new pods with multisigs for pushing through changes. When a Pod submits a new proposal, it is queued into a timelock for 96 hours before being automatically executed on-chain. During this timelock, The Nope Dao can review the proposal and veto it if they are not in favor by voting 10 million TRIBE

The Security Guardian is the final layer of security for Tribe, occupying a similar position as Aave’s Guardian Account. It is a 3 of 7 multisig controlled by Fei Labs and can pause contracts as well as veto proposals put forward by token holders or Pods.

Fei-Rari Merger and the Tribe DAO Unwind

In December 2021, Fei Protocol merged with Rari Capital in the largest DeFi merger to date. Twoproposals were put forward concurrently by the founders of the protocols outlining the deals of the merger in November 2021 and debated over the course of a month before proceeding. Key components of the deal included the swap of Rari’s governance tokens (RGT) for TRIBE; the ability for holders of TRIBE that disagree with the agreement to sell out of their position; and the compensation of RGT holders who suffered from a previous hack of Rari.

The Fei/Rari merger represented a significant milestone for DeFi governance. While the initial idea and strategy was incepted by the founders of Fei and Rari and their core teams, it was discussed, voted on, and implemented entirely through the two protocol’s respective governance mechanisms. This differs to prior mergers like Polygon-Hermez, where the decision was made and executed entirely by the teams with little input from the community. Additionally, what would normally have taken months of legal work and negotiations in traditional finance was completed in less than a month with the backing of each community – with 91% (Fei) and 93% (Rari) voting in favor.

The aftermath of the merger, however, has also highlighted the downsides of a decentralized governance model that lacks the thoroughness and regulation of the traditional financial system, including the incentives to ensure that the original reasons for the merger are consummated. Less than six months after the merger, the Rari development team announced it was leaving the protocol. The opportunity for the Fei and Rari team to collaborate had been a key advantage highlighted in the initial proposal.

Soon after the merger, the Rari protocol was also hacked and lost $80 million, requiring Fei to again bail out holders. This could point toward a failure on the part of the governance process to properly conduct a comprehensive risk analysis of the merger. Holders have faced difficult decisions on whether to reimburse the hacked victims, who should do it, and how. While an initial informal Snapshot vote in May indicated broad support for compensating victims, it failed to detail how, and an on-chain vote was quickly vetoed by The Nope DAO.

Finally, in August, the Fei team announced they would end their participation in the Tribe DAO and proposed a consolidation of the protocol’s assets so that it could continue to run without any governance. The proposal, now passed, also included another proposal for compensating the hack victims, representing the third time in less than a year that the issue had to be voted on and making it one of the final governance decisions Tribe DAO will make.

While there is no question that developments over the past year point to the failures of the Tribe DAO in successfully executing a lasting merger (the protocol is currently in the process of unwinding), the actual mechanics of Tribe’s governance process worked as intended. Governance oversaw the launch, growth (through a merger), and unwind of the protocol. Throughout, holders were able to step in and veto proposals, even if they had formally been approved.

The events and the way they unfolded highlight an important distinction between building a consensus and an informed consensus. It is easy for protocols to pass new proposals that on the surface appear to bolster the underlying value of their tokens. It is exceedingly difficult for those proposals to actually account for everything that might go wrong and ensure that those voting on them understand the full risks. Had voters initially understood the ramifications of the merger and its possible implications, the Tribe DAO might have not gone through with many of the actions that are now partly behind its unwind.

As Fei’s founder tweeted following the most recent vote to repay hack victims, “The biggest lesson here is that DAOs should not have to make decisions like this after the fact. An explicit upfront policy, ideally with on-chain enforcement, would have saved the DAO from needing to venture into uncharted governance territory.”

Curve

Curve Finance was launched in August 2020 and has since grown to become a leading automated market maker (AMM), primarily focused on swaps between stablecoins and other closely correlated cryptocurrencies. Curve’s proprietary swap formula enables users to swap high volumes of stablecoins at low slippage relative to other AMMs.

Governance

Liquidity providers on Curve earn CRV token rewards. CRV is the Curve token and is used for staking, boosting, and voting. Holders can stake their CRV to earn a percentage of trading fees generated by the Curve protocol in the form of LP tokens.

To vote on Curve governance mechanisms, holders must lock their CRV tokens in return for Voting Escrowed Curve (veCRV). The longer a user locks up their CRV, the more veCRV (i.e. voting power) they receive. This incentivizes users to lock up their CRV for longer to receive more voting power. It also reduces the supply of circulating CRV. As you get closer to the end of your lockup period, the amount of veCRV (i.e. voting power) a user has declines. To increase their voting power again they must either buy more CRV and lock it up for veCRV or wait until their current veCRV unlocks and re-lock it.

Users can lock up their CRV for 1 week to 4 years, with 4-year lockups receiving the most veCRV. Curve also incentives users to lock up their CRV by boosting their liquidity rewards, the amount of CRV they receive for being a liquidity provider. Users can earn a boost of up to 2.5x maximum for holding more veCRV. veCRV uses a non-standard ERC20 token contract that prevents users from transferring veCRV to others and redeeming it for CRV early.

Curve uses two voting mechanisms: Snapshot and DAO proposals. The Snapshot is used for signaling proposals by the community. Users create a post on Curve’s governance forum to gather feedback from the community and then post it to Snapshot to gauge sentiment. The only requirement for creating a new Snapshot proposal is that the user holds at least 1 veCRV. As with other protocols like Uniswap and Aave, Snapshots are non-binding.

DAO proposals are Curve’s formal governance process and how changes are made to the protocol. To submit a new proposal, users must hold 2,500 veCRV. DAO proposals making protocol parameter changes require a 15% quorum of all veCRV while ownership votes (such as adding a new Gauge) have a quorum of 30%. While a user can submit a new DAO proposal directly if they meet the 2,500 veCRV requirement, more often they follow Curve’s informal governance procedures of creating a forum post, initiating a Snapshot vote, and then submitting a DAO proposal.

Curve uses a custom version of Aragon–a DAO tooling provider–for its governance contracts. Approved DAO Proposals are automatically executed on-chain once approved. Proposals that are not executed automatically must indicate who will develop and implement the changes (usually the Curve core development team, but not always).

Curve also has a Curve Emergency DAO that can act if there is a malicious attack of the protocol. The Emergency DAO has a multisig consisting of nine members who are elected by the Curve DAO. They can be added or removed at any time through DAO proposals. The Emergency DAO can disable the Curve protocol except for withdrawals. This requires 59.9% of Curve Emergency DAO multisig holders to vote in favor of the proposal with a 51% quorum. This can be overturned by the Curve DAO through a DAO proposal.

Curve Wars

Governance votes in Curve primarily revolve around determining and modifying the allocation of CRV emissions (protocol inflation). veCRV can be used to direct CRV emissions to Curve’s various liquidity pools. Users can use their veCRV to vote on specific Gauges (liquidity pools) to dictate where CRV emissions are distributed. The more veCRV that is deployed to a Gauge, the more CRV rewards it earns.

Other protocols that want to attract more liquidity and reduce slippage for swaps using their token may accumulate veCRV to direct more CRV rewards to their Gauge. This, in turn, increases the yield of the pool and incentivizes more liquidity. This has led to “The Curve Wars,” where protocols battle to accumulate veCRV to make their pools the most attractive for liquidity providers.

Convex

Convex is a protocol built specifically to optimize the yields users can earn from CRV emissions. On Convex, users swap their CRV for Convex CRV (cvxCRV) or can deposit their Curve liquidity provider (LP) tokens. They can then stake those CVX tokens or LP tokens to earn the same rewards they would have had they staked their CRV directly on Curve, in addition to earning CVX rewards.

The benefit for Convex users is that they earn a greater yield than had they simply staked their CRV on Curve directly because (1) Convex continually locks up deposited CRV for the longest period, increasing the boost that LPs earn, and (2) users earn both CRV rewards and CVX rewards. Additionally, users hold a more liquid version of their CRV as they can trade out of their cvxCRV at any time throughs secondary markets (remember that veCRV is non-transferrable).

The tradeoff of earning higher yields and liquidity is that cvxCRVs holders lose their governance power–the ability to vote on proposals and direct CRV rewards–since they no longer hold veCRV, only cvxCRV. To address this, Convex enables users to lockup their CVX, which they earn from their cvxCRV, in exchange for Voter Locked CVX (vlCVX). By locking up their vlCVX for 16 weeks, users can use the Convex Snapshot governance platform to vote on Gauges and increase the CRV rewards for that Gauge. The results of votes (i.e. the distribution of veCRV to various Gauges) are then executed by a Convex 3 of 5 multisig consisting of members from Convex, Curve, Votium, and Frax. While the multisig should act according to vote results, they are not required to do so. As the Convex documentation reads, “Convex Finance multi-sig is still required to sign to establish outcomes of all CVX Snapshot votes, for both governance and Curve gauge weight votes. In almost all cases, we will vote in-line with CVX holders. However, Convex and Curve benefit each other, and proposals considered to be blatant attacks damaging either protocol will not be signed for.”

Given the large voting power of Convex–Convex controls nearly 56% of Curve’s voting power–this could present an opportunity for the Convex multisig to unilaterally affect the outcome of a vote despite the wishes of holders. To date, this has not been an issue given the aligned interests of the multisig and the synergistic Curve-Convex relationship in which the success of one amplifies the success of the other.

If this entire dynamic between Curve and Convex sounds confusing, that’s because it is. And participating in this multi-protocol governance layering requires significant DeFi acumen on the part of users. But there are billions of dollars at stake, and these are composable and mostly permissionless protocols, so the emergence of complex manipulation schemes should come as no surprise.

Bribing

Another important layer to Curve’s governance is bribing. Initially, protocols focused on accumulating veCRV to increase the rewards liquidity providers to their pool receive. Over time, especially following the launch of Convex, protocols realized it was more cost efficient to bribe holders rather than outright buy CRV. Instead, protocols allocate rewards (in their native token for example) to incentivize users to vote for their pool to receive more CRV emissions.

This has led to the launch of several new protocols such as Votium and Bribe to streamline this process and more efficiently accumulate votes. Votium, for example, has a function that enables users to deposit their vlCRV and have it automatically allocated to Gauges with the highest paying bribes. This is beneficial for both vlCRV holders and protocols. vlCRV holders are given the opportunity to earn more yield on their assets. At the height, vlCRV holders could earn an additional ~$0.87 per vlCRV they held. Protocols have a more capital efficient way to increase their pool rewards and can even make money through bribes due to the increase CRV rewards they earn (currently, for every $1 a protocol spends on bribe they earn $1.32 in CRV and CVX emissions).

Conventionally, bribing has negative connotations. In Curve, however, it has spawned a governance mechanism where votes are efficiently allocated to the most profitable strategies, earning CRV holders the highest yield while providing protocols with an efficient means of bootstrapping liquidity. At its core, this dynamic works because of the synergistic relationships between Votium, Convex, and Curve: Convex amplifies users CRV rewards, especially for smaller holders who benefit from the boost they gain by holding cvxCRV, and Votium further amplifies them. Since all parties are aligned in their end objective, each additional layer of governance enhances rather than detracts from Curve governance overall.

Yield Governance

Curve is one of the best examples of the intersection of DeFi and governance. Governance plays a critical role in dictating the yield of CRV holders by controlling how CRV emissions are distributed. This has spawned new protocols like Convex that manage yield optimization but require users to forfeit their governance power (remember, cvxCRV holders earn a higher yield but do not have the same governance rights as veCRV). On top of that, protocols like Votium then enable protocols to bribe users for their votes, reinforcing the role of yield as the primary driver of decision making. In short, the feedback loop between yield and governance is so directly correlated that governance on Curve is driven by yield above all else, aligning governance across protocol participants no matter what platform they are using. Higher yields lead to more concentrated liquidity which leads to lower slippage – the major value proposition of Curve.

Curve’s model does raise concerns over the entrenchment of governance power, particularly as it relates to the directing of CRV emissions. A protocol that accumulates significant CRV– which they could do through being a LP, buying CRV off secondary markets, or using other protocols like Convex–can more cheaply attract future liquidity because they can allocate more CRV emissions to their liquidity pools. Frax has pursued this strategy aggressively and now receives ~32% of all newly emitted CRV even though it only accounts for just over 1% of total volume on the Curve protocol. This raises questions about the role of governance in directing CRV emissions to the most used liquidity pools rather than the ones able to provide the highest yield.

In 2021, a DeFi protocol Mochi attempted to take advantage of this dynamic. Mochi purchased ~$46 million in CVX to direct more CRV rewards to their liquidity pools and incentivize deeper liquidity. However, shortly after initiating the scheme, Curve holders uncovered several red flags surrounding Mochi protocol’s operations and means of obtaining the CVX, prompting concerns over the allocation of so many CRV tokens to a potentially fraudulent protocol. In this case, Curve’s Emergency DAO was able to respond quickly and prevent the Mochi liquidity pool from receiving CRV emissions. The event, however, created significant controversy over the power of the Emergency DAO as well as the ability of questionable protocols to hijack CRV emissions for their own benefit.

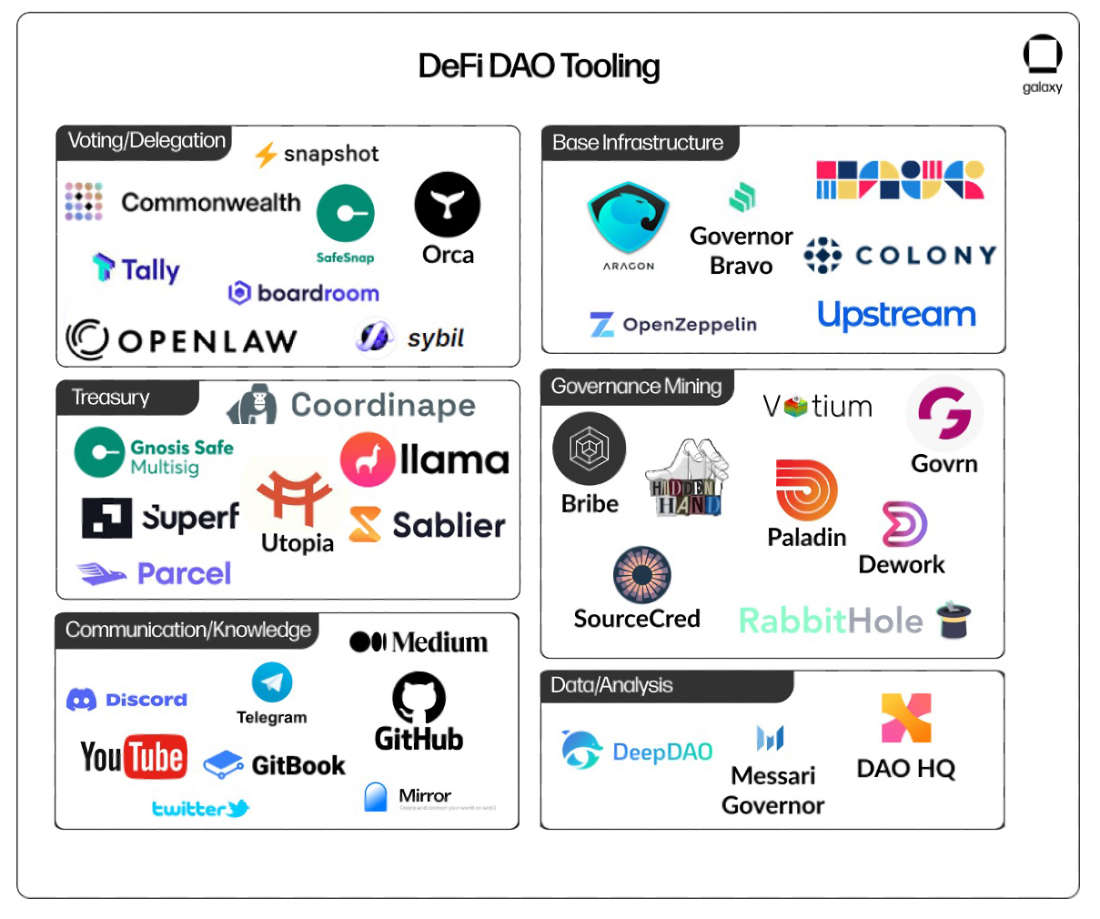

Governance Tooling

In addition to protocol-native tooling, in recent years a number of governance tools have emerged to improve the governance process. For protocols, these tools can offer everything from the basic infrastructure needed to create an on-chain governance system (i.e. Governor Bravo and Aragon) to automated incentive mechanisms that reward community members who are active in governance (i.e. SourceCred). For voters, these tools play an increasingly important role in driving greater engagement by providing better user experiences and aggregating information and knowledge.

Governance tooling categories include:

Base Infrastructure: The fundamental building blocks of DAO governance. Base infrastructure offerings provide customizable on-chain and off-chain governance mechanisms for a protocol to launch a decentralized governance process.

Treasury: Improves transparency and security of protocol funds owned by the community. This includes treasury management, white label multisig solutions, and DAO compensation.

Communication and Knowledge: Provides mediums for protocols and community members to relay information and engage with each other.

Voting and Delegation: Offers protocols and users improved voting and delegation interfaces.

Data/Analysis: Provides data and analytics into DeFi governance metrics like proposals, votes, and participants.

Governance Mining: Creates incentive mechanisms to reward participants that partake in a protocol’s governance process.

Still early in their development, governance tooling offerings have expanded rapidly in recent years as demand grows for customizable and simple tools that increase transparency and reduce user friction during the governance process.

Below we have included an ecosystem map outlining the top governance tools used in the DeFi ecosystem today.

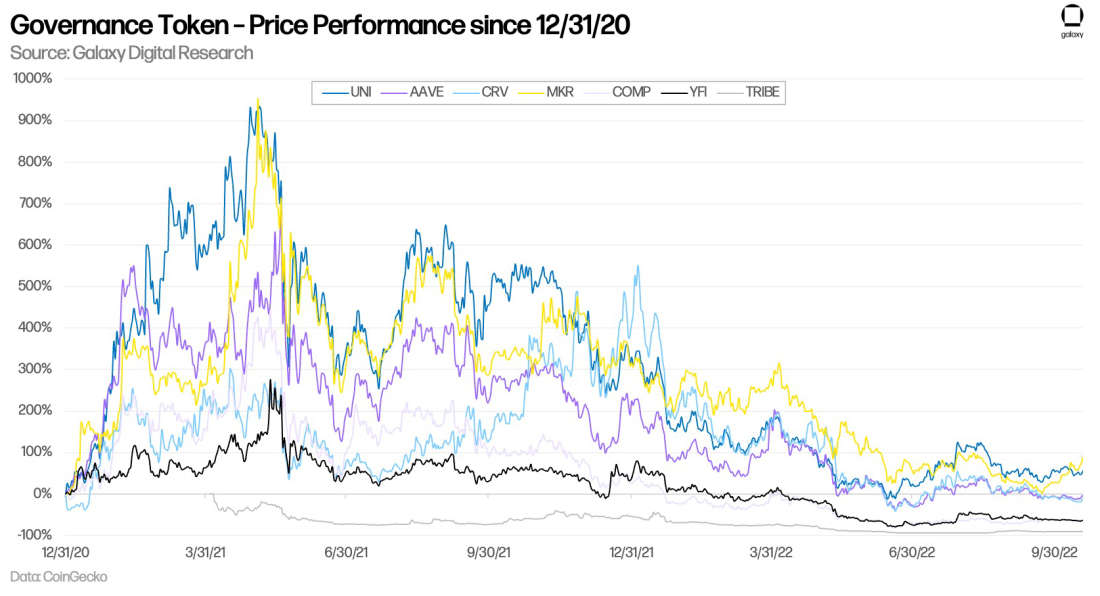

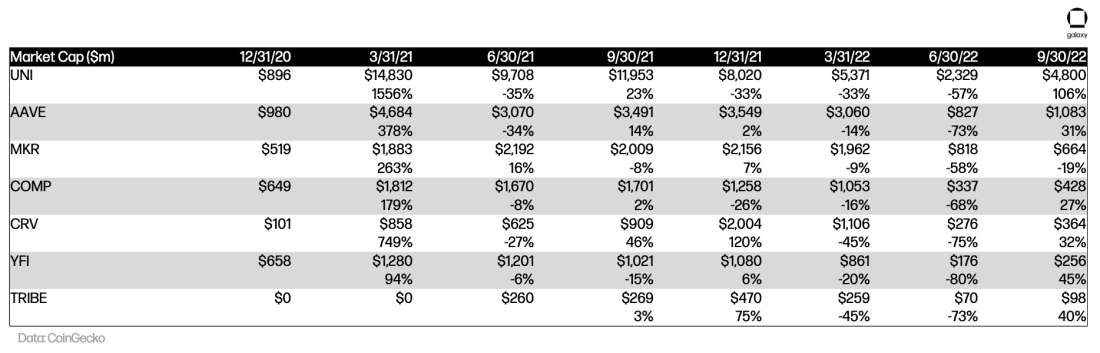

Governance Token Performance

Key Takeaways

Two Steps Forward, One Step Back:

DeFi has made incremental progress toward creating a more decentralized and equitable governance process that empowers the community and limits centralization. Key accomplishments include:

The introduction of governance tokens that empower holders to vote on new proposals.

A movement away from centralized governance processes reliant on founding teams and multisigs to submit new proposals and implement upgrades.

Off-chain voting interfaces like Snapshot that provide a simple and cost-free means for token holders to vote on new governance initiatives.

Automated on-chain governance processes with the capability to update the protocol without the need for a centralized multisig.

Compound’s open-source Governor Bravo contract which enables any new protocol to quickly spin up a tried and tested governance mechanism without significant work from development team.

Frameworks like Maker’s Core Units and Yearn’s Constrained Delegation model that attempt to find a balance between decentralized governance and centralized execution.

These improvements, however, have also revealed new problems that need to be addressed. The introduction of governance tokens has led to the large concentration of voting power amongst whales; governance automation has exposed protocols to new vulnerabilities that can’t be responded to in real time; and protocols continue to struggle to balance the tradeoff between decentralization and execution. The rapid pace of innovation in DeFi necessitates governance structures that can move just as quickly. While DeFi governance has come a long way, it still has even farther to go.

Governance Tokens

Governance tokens create greater agency amongst a protocol’s community. In its current iteration, however, governance token voting largely resembles a plutocracy where the largest holders have the biggest say. In extreme cases, few uninterested voters may have more power than thousands of smaller but incredibly engaged ones. This can have negative knock-on effects like voter apathy.

Looking forward, improvements include:

Delegate Voting. Already in use by several protocols, delegate voting helps to mitigate voter apathy by concentrating voting power amongst engaged community members. This can limit the power of the largest holders to dictate what proposals do and do not pass. Delegate voting can be enhanced by leveraging Governance Mining (discussed below).

Quadratic Voting. This voting solution makes each additional vote a user casts cost exponentially more. For example, say you have two users – one is a “whale” with 100 tokens and the other a “minnow” with 16 tokens. If the whale allocates all their tokens, it will only represent 10 total votes (10 is the square root of 100) and if the minnow allocates all their tokens, it will represent 4 votes (4 is the square root of 16). This mechanism can help to lower the power of large holders of a governance token while providing smaller holders with a larger voice. Gitcoin, an Ethereum based grants protocol, has already implemented a variation of this through Quadratic funding.

Know Your Customer (KYC). Implementing KYC requirements would enable protocols to enact voting mechanisms where each unique user gets the same amounts of votes, something that is impossible to implement today given wallets can be anonymous and an individual users can spin up multiple wallets to gain greater voting power. However, this could disincentivize users from holding governance tokens and would require major revamps to existing governance tokenomics. Breakthroughs in zero knowledge proofs could enable the use of KYC without requiring users to reveal their identity on-chain.

New Governance Token Structures.Optimism’s dual token approach is an innovative approach to governance token design. Early optimism users were airdropped two tokens: a traditional governance token that follows the one-token-one-vote model and can be used for voting on updates to the protocol’s parameters; and a soulbound non-transferrable NFT for allocating protocol revenue for retroactive public goods funding. The dual-token design is meant to give users a say in both the protocol’s governance and use of funds, and points toward the ability for projects to experiment with new designs rather than reverting to the norm.

Governance Complexity

As DeFi protocols mature and grow their governance processes often become more complex. This requires users to make informed decisions on issues that may be beyond their understanding.

Protocols will be challenged to devise structures that empower holders to determine the direction of the protocol at a high level without constraining the ability of subject matter experts to efficiently execute it. New governance structures such as Maker’s Core Units, Yearn’s Constrained Delegation, and voting delegation represent the first of many iterations in tackling this dilemma. However, as evidenced in ongoing debates over the future of the Maker protocol, they have also raised questions about centralization of power and transparency.

DeFi governance today is an incredibly involved process that requires users to comb through discords and telegrams, read lengthy and complex forum posts, and keep track of upcoming vote timings. For the average user this can disincentivize participation as they do not have the time or energy to commit. To encourage greater community participation, protocols and third-party providers need to develop more user-friendly tools that streamline information flows in an objective and informative way. Governance tooling like Tally, Snapshot, Gnosis, Orca, and Messari Governor are just a few projects working toward this vision. Longer term, as the on-chain environment settles on best practices, the crypto community should establish and propagate standards for on-chain governance.

Protocols should also consider the use of Governance Miningframeworks as a way to incentivize better user engagement in the governance process. Governance Mining requires protocols to set aside a set portion of their governance tokens to be distributed to users who contribute to the protocol – itself a difficult and often subjective metric. Tools like SourceCred – which quantify user engagement and contribution – can be leveraged to incentivize users that want to be active in the governance process but don’t have the bandwidth or time to contribute regularly. To date, protocols like Maker are leading the way in testing these concepts, rewarding delegates for providing active feedback and consistently participating in votes.

There is a growing number of DAO governance service providers/consultants sprouting up. Bored Ghost Labs, for example, is a group of prior Aave contributors who have spun out to create their own entity that will now provide paid consulting services to implement further updates to the Aave protocol. The professionalization of DAO governance is likely to accelerate in the coming years as additional third-party service providers leverage their past experiences to advice new and existing DAOs. Current leaders in the space include Gauntlet, Chaos Labs, and Reverie. Furthermore, we expect that governance analysis to become commonplace, with firms providing advice on voting to governance token holders, as firms like ISS do for equity proxy voting.

Centralization > Decentralization > Centralization

Simple direct democracy one-token-one-vote designs are not sufficient for DeFi protocols to operate efficiently and underwrite complex financial transactions. In response, protocols are devising hybrid governance structures that optimize the decision-making and execution process by incorporating more traditional corporate structures. Maker’s Core Units, Yearn’s Constrained Delegation, and Fei’s Pods highlight this trend. Other notable DeFi projects like Element Finance (which has a Governance Steering Council) and Synthetix (with its Spartan Council) have also implemented similar models. These models, combined with voting delegates, still leaving varying levels of power in the hands of governance token holders who can appoint and remove decisionmakers. Relative to traditional corporate governance, they also tend to be more transparent as discussion and debate happens on public governance channels.

But decentralization exists on a spectrum. The ultimate objective of a protocol may not always be to be decentralized, but instead to maximize returns to their holders by incorporating blockchain technologies that offer advantages in terms of composability and security compared to their traditional finance offerings. As @ChainLinkGod wrote in a recent thread on the topic, “Not every blockchain-based financial application is aiming for maximum trustlessness and decentralization. Many are hybridization, where components of varying levels of trust-minimization are comped together.”

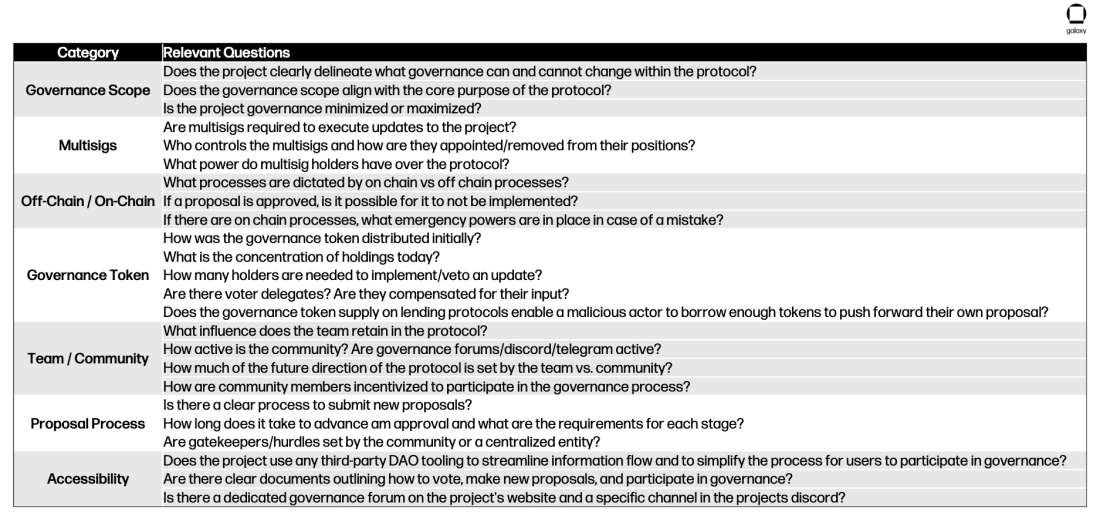

DeFi Governance Evaluation Framework

Below we have outlined a set of questions and criteria that individuals can use as a framework for evaluating the governance systems of DeFi projects:

Conclusion

Projects like Maker, Aave, and Uniswap have cemented their position as DeFi financial primitives. Each has weathered setbacks. At times, they have even failed. But their design and technology now serve as a foundation that new protocols replicate and iterate on.

As one of the leading crypto use-cases, DeFi has also helped set the standard for many of the basic governance structures protocols take for granted today. To ensure long-term success, however, projects must continue to innovate. Governance is ultimately a social layer of the crypto ecosystem. It is complex, involved, and highly political process. It is also essential to the decentralized operation of any protocol or application.

Effective governance should drive growth and innovation of the protocol without constraining operational efficiency and sacrificing security. It’s an incredibly difficult balance. Every user brings new opinions and perspectives. There are no one-size fits all models. And every protocol will have to grapple with the tradeoffs of the choices they make. Critical to getting governance right is for projects to first determine their core objective. Only then is it possible to decide on a suitable scope and mechanism for governance.

Legal Disclosure:

This document, and the information contained herein, has been provided to you by Galaxy Digital Holdings LP and its affiliates (“Galaxy Digital”) solely for informational purposes. This document may not be reproduced or redistributed in whole or in part, in any format, without the express written approval of Galaxy Digital. Neither the information, nor any opinion contained in this document, constitutes an offer to buy or sell, or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell, any advisory services, securities, futures, options or other financial instruments or to participate in any advisory services or trading strategy. Nothing contained in this document constitutes investment, legal or tax advice or is an endorsementof any of the digital assets or companies mentioned herein. You should make your own investigations and evaluations of the information herein. Any decisions based on information contained in this document are the sole responsibility of the reader. Certain statements in this document reflect Galaxy Digital’s views, estimates, opinions or predictions (which may be based on proprietary models and assumptions, including, in particular, Galaxy Digital’s views on the current and future market for certain digital assets), and there is no guarantee that these views, estimates, opinions or predictions are currently accurate or that they will be ultimately realized. To the extent these assumptions or models are not correct or circumstances change, the actual performance may vary substantially from, and be less than, the estimates included herein. None of Galaxy Digital nor any of its affiliates, shareholders, partners, members, directors, officers, management, employees or representatives makes any representation or warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy or completeness of any of the information or any other information (whether communicated in written or oral form) transmitted or made available to you. Each of the aforementioned parties expressly disclaims any and all liability relating to or resulting from the use of this information. Certain information contained herein (including financial information) has been obtained from published and non-published sources. Such information has not been independently verified by Galaxy Digital and, Galaxy Digital, does not assume responsibility for the accuracy of such information. Affiliates of Galaxy Digital may have owned or may own investments in some of the digital assets and protocols discussed in this document. Except where otherwise indicated, the information in this document is based on matters as they exist as of the date of preparation and not as of any future date, and will not be updated or otherwise revised to reflect information that subsequently becomes available, or circumstances existing or changes occurring after the date hereof. This document provides links to other Websites that we think might be of interest to you. Please note that when you click on one of these links, you may be moving to a provider’s website that is not associated with Galaxy Digital. These linked sites and their providers are not controlled by us, and we are not responsible for the contents or the proper operation of any linked site. The inclusion of any link does not imply our endorsement or our adoption of the statements therein. We encourage you to read the terms of use and privacy statements of these linked sites as their policies may differ from ours. The foregoing does not constitute a “research report” as defined by FINRA Rule 2241 or a “debt research report” as defined by FINRA Rule 2242 and was not prepared by Galaxy Digital Partners LLC. For all inquiries, please email contact@galaxydigital.io. ©Copyright Galaxy Digital Holdings LP 2022. All rights reserved.