This report is part 2 of a 2-part series focused on Maximal Extractable Value.

Key Takeaways

The MEV supply chain has become more complex since the creation of MEV-Boost, the standardized software proof-of-stake (PoS) validators on Ethereum use to earn MEV.

New stakeholders, known as builders, are responsible for constructing a full block containing transactions optimized to maximize rewards from priority fees and MEV.

Builders specialize in developing proprietary models for simulating blocks and propagating them efficiently through off-chain MEV marketplaces known as relays.

Because of the specialized skills required to be a builder on Ethereum, there is a concern that the builder landscape will become centralized over the long term.

To combat the negative network effects of builder centralization, Ethereum developers and the Flashbots team are discussing several potential solutions, such as inclusion lists, partial block auctions, and S.U.A.V.E.

Introduction

Between January 1, 2022, and December 31, 2022, $133m in Maximal Extractable Value (MEV) was earned on Ethereum. (The data featured in the chart below contains updated figures from Flashbots according to a new methodology for identifying MEV on Ethereum, which is why numbers may differ from what was featured in last year’s MEV report by Galaxy Research).

Year-over-year, the total amount of MEV created in 2022 was significantly lower than the amount of MEV created in 2021 in part because of the steep decline of decentralized finance (DeFi) activity on Ethereum as a result of bear market conditions. In addition, increased competition between MEV searchers has also contributed to making DeFi markets more efficient and thereby reducing MEV profit margins. Up until the end of Q3, most MEV earnings accrued to Ethereum miners. However, following the activation of the Merge upgrade, most MEV earnings started to accrue to validators because they replaced miners as the network’s primary security providers and block proposers. (On Ethereum, validators represent staked deposits of 32 ETH. For more information about validators and the Merge upgrade, read this Galaxy Research report).

As of December 2022, roughly 80% of all Ethereum validators are earning MEV through a neutral third-party software known as MEV-Boost. MEV-Boost, which was architected by Flashbots in partnership with Ethereum core developers, is software that enables validators to connect to multiple off-chain marketplaces for auctioning block space, also known as relays. Through relays, validators receive blocks containing priority fees and MEV built by third-party block builders.

Third-party builders and relays are new entities in the MEV landscape of Ethereum made possible because of the advent of MEV-Boost software, as well as the open-sourcing of both builder and relay code. Historically, Flashbots was the only operator of a relay, and mining pools connected to the Flashbots relay to earn MEV. However, because of MEV-Boost and the open-sourcing of relay technology, other MEV relays such as the Dreamboat relay operated by Blocknative are starting to compete with the Flashbots MEV-Relay and help decentralize MEV infrastructure. The Flashbots MEV-Relay is still by far the most popular relay, producing 81% of MEV-Boost blocks.

The long-term incentives for a diversity of relays to persist on Ethereum remains unclear. In addition, there is the concern is that over time the specialization of builders coupled with the rise of payment for order flow (PFOF) activity favors the dominance of a single builder. Due to the fact MEV-Boost is designed to support only full block auctions, there is another concern that transaction censorship by dominant MEV infrastructure operators such as Flashbots results in the degradation of the network’s credible neutrality. As of January 20, 2023, about 67% of blocks produced daily on Ethereum are actively censored by a relay.

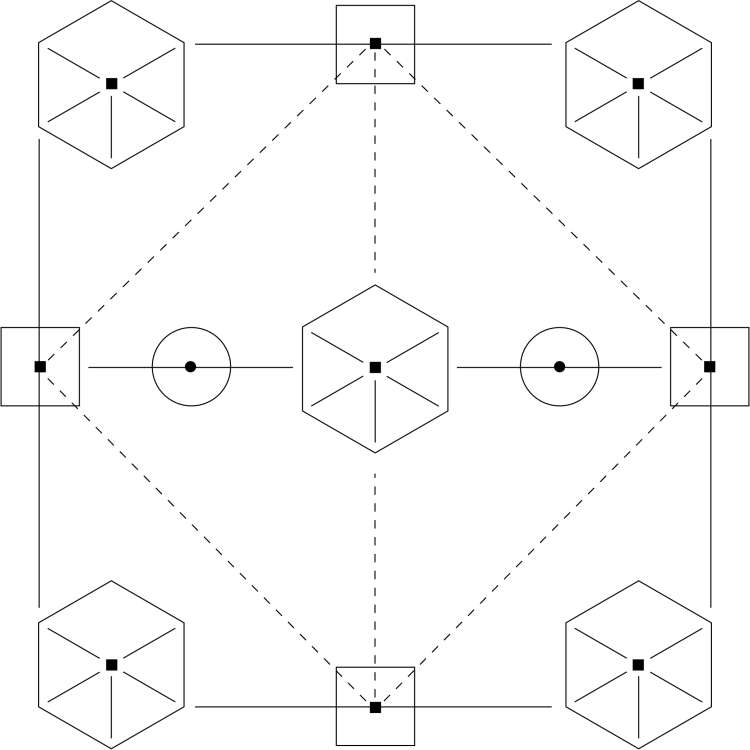

This report will give an overview of the revamped MEV landscape of Ethereum post-Merge. First, we will give an overview of MEV-Boost architecture and its main stakeholders including searchers, builders, relays, and validators. Then, we will discuss concerns around relay censorship and builder centralization because of MEV-Boost and the long-term solutions Ethereum core developers and the Flashbots team are developing to tackle these issues. For a deep dive into the basics of MEV on Ethereum including what it is, how it is created, and its parallels to traditional finance, read this Galaxy Research report as a precursor to this report.

An overview of MEV-Boost

MEV-Boost is an early implementation of Proposer Builder Separation (PBS) on Ethereum. PBS refers to splitting the responsibility of block building and block proposing into two separate roles. Traditionally, the security provider of a public blockchain, be it a miner or validator (or a pool comprised of either), is responsible for building blocks containing user transactions and submitting these blocks for verification to the network. Under PBS, the role of the security provider is isolated to block proposing, while the responsibility of block building is offloaded to a third party. The motivation for splitting these responsibilities is to reduce the amount of specialized knowledge and hardware needed to operate an Ethereum validator. By ensuring competition between validators does not depend on specialized skills or equipment, the barrier to entry for new participants to enter the validator pool remains low. Encouraging as many participants as possible to contribute to the security and decentralization of Ethereum is the main goal of PBS.

MEV-Boost is a preliminary step for realizing the full vision of PBS because the MEV-Boost software relies on off-chain marketplaces, also called relays. The role of relays is to ensure honest behavior between builders and validators by checking block reward payments, monitoring activity between participants, and ensuring that validators do not front run builders by stealing their blocks. The full vision of PBS cuts out the trusted role of relays and enshrines the rules of honest participation between builders and validators into the protocol layer of Ethereum. Due to the complexity of the Merge upgrade, Ethereum core developers agreed to delay the encoding of PBS to Ethereum’s protocol layer. In the meanwhile, to address the immediate impact of MEV dynamics on validators, Ethereum core developers and the Flashbots research and development team created MEV-Boost.

MEV-Boost is a “side car” software that is run alongside the core software (that is, a dual execution layer and consensus layer client software package) needed to operate an Ethereum validator. By running MEV-Boost software, validator node operators can connect to multiple relays and start to accept pre-built blocks from builders containing MEV. Validators only receive the block reward amounts and block headers from relays. They do not see the contents of a block before the block is included on-chain. This level of privacy ensures that validators cannot front-run builders by copying and rebuilding blocks built by third-party builders. It is estimated that blocks produced through the Flashbots MEV-Relay are twice as profitable than other blocks. Locally built blocks refer to blocks that validators build themselves from their local view of the Ethereum mempool. Blocks sourced from relays are built by builders who are packaging transactions from searchers, private orderflow (meaning direct from individuals and entities), as well as the local mempool.

In the next section of this report, we will dive into the key characteristics of searchers, builders, validators, and relays.

Searchers

Searchers identify opportunities to extract MEV by ordering the execution of user transactions within a block. They are actively monitoring the public mempool and identifying profit-maximizing ways to extract value from user transactions, sometimes by causing increased slippage and worse execution on decentralized exchanges (DEXs). For more information about MEV types and strategies, read this Galaxy Research report. The strategies for MEV often mimic practices in the traditional stock market such as frontrunning, sandwiching, stop hunting, and arbitrage. The MEV strategy that extracted the most amount of value in 2022 was arbitrage. According to EigenPhi, arbitrage accounted for roughly half of all MEV revenue generated in 2022. The following chart illustrates daily arbitrage revenues earned by searchers as a percentage of total MEV revenues:

While some types of MEV are beneficial to end-users, such as arbitrage and backrunning, others like sandwiching are not. Certain decentralized exchanges (DEXs) such as CowSwap aim to reduce negative MEV on-chain by making order execution that benefits end-users more lucrative. On CowSwap, specialized searchers called solvers are bidding for the right to execute user trades on-chain. The solver that can offer the best order execution will be able to offer users the most competitive price for their transactions. Solvers may gain a competitive advantage over other solvers by striking an exclusive relationship with a builder to get user transactions executed at the top of a block or by minimizing trade slippage through combining multiple user trades together. There is nothing to prevent the execution of user transactions by a solver from being frontrun or sandwiched by a regular searcher. However, in these scenarios, solvers are the ones that pay the cost for poor order execution, as a solver’s payment to users for their transactions occur before any transactions are executed on-chain.

There are over 10 solvers on CowSwap competing for user trades. However, CowSwap is only one DEX among several on Ethereum where monitoring user trades and bundling them can be a lucrative activity. On other DEXs such as Uniswap and Curve, user execute their own trades on-chain directly and general searchers bid for the right to re-order their execution on relays, which will be discussed in more detail later in this report. The most profitable and skilled searchers on Ethereum are the ones that are experts at monitoring and analyzing on-chain activity, particularly decentralized finance (DeFi) trades. Searching also requires a strong knowledge of financial markets and trading, as these skills are critical for identifying and exploiting market inefficiencies that create MEV. The following is a table of the top 10 most competitive MEV searchers on Ethereum in 2022:

MEV is a zero-sum game. There are a limited number of opportunities to extract value from reordering transactions and the fastest searcher to identify MEV opportunities is often the searcher to earn the most MEV. To maximize earnings, competitive searchers will write scripts to automate the task of exploiting easily identifiable opportunities for MEV. In addition, searchers may run dedicated hardware or subscribe to paid services that offer low latency views of the Ethereum mempool to take advantage of pending user transactions more quickly. To outcompete other searchers, seasoned and sophisticated searchers may deploy complex strategies involving multiple token swaps, bots, and manual searching through on-chain activity to achieve higher profits. For a detailed view of a searcher’s arbitrage strategy on Ethereum and later Avalanche, read this blog post by Google Product Manager Daniel McKinnon. For a detailed overview of more complex MEV strategies, read this Twitter thread by Flashbots Product Lead Robert Miller.

Builders

Builders are the new stakeholders in the MEV supply chain responsible for packaging transaction bundles from searchers, along with individual transactions from the public mempool and private transaction order flow, into blocks. Builders are themselves searchers in some capacity as the task of building a maximally profitable block does not depend on reordering searcher bundles alone—it also depends on simulating how block space not occupied by bundles can be filled with profitable transactions from the mempool and other sources. This latter activity requires some knowledge of basic searching strategies. While searchers may specialize in the task of extracting MEV from specific DeFi protocols, builders generally have a wider view of eligible transactions for inclusion in a block and specialize in the task of full block simulations from multiple sources.

Sophisticated hardware

The task of simulating multiple bundles and transactions in a block, calculating, and evaluating their worth, is computationally intensive and requires sophisticated hardware such as the operation of multiple full nodes. Builders like searchers must ideate their own unique techniques for efficiently simulating full blocks based on incoming transaction data. Builders will generally wait until the last possible moment before proposing a full block to maximize the amount of potential MEV for inclusion in the block, which requires extremely low latency for proposing blocks and views of the Ethereum mempool.

The task of packaging searchers’ transaction bundles into blocks used to be the responsibility of miners and mining pools before the Merge. It comes as no surprise then that one of the top builders on Ethereum, Builder 0x69, is themselves a former mining pool operator, according to the user’s pseudonymous Twitter profile.

Before the Merge, miners expended most of their electricity solving a mathematical puzzle, also called a hash function, as many times as possible. The first miner to find an acceptable hash would have the right to propose the next block. Miners also expended electricity on ordering and reordering transaction bundles from searchers to maximize the rewards they could earn from a block. Fast forward to January 2023, now validators, who have replaced miners, expend little to no electricity to propose a block on Ethereum. They are randomly elected by the protocol. In addition, if they are not earning MEV-rewards and building a block from their local mempool, validators will order transactions within a block by high to low priority fee. No complex block simulations necessary. Builders, on the hand, rely on similar strategies as the ones used by competitive mining pools pre-Merge to maximize the MEV they can earn in block.

Searcher collaboration

In addition to sophisticated hardware, builders rely on close collaboration with specialized searchers that identify MEV from strategies more complex and profitable than their own. From the perspective of searchers, a builder may front run searcher bundles and steal their MEV, which is why some searchers choose to operate their own builder if they have sufficient capital and resources to do so and why a trusted reputation as an honest builder is key to facilitating close collaboration between specialized builders and independent searchers. Beyond close collaboration with searchers, builders also compete through private or exclusive order flow. Blockchain infrastructure company Blocknative, which operates a builder and a relay, estimates that roughly 3.8% of transactions in a block built by a third-party builder is sourced from private sources, outside of the public mempool.

Block subsidies

Once a builder has settled on a profitable block, they calculate a bid that is included in the block either as a lucrative priority fee or as a direct transfer from builder to validator at the end of a block. The higher the bid, the more likely a builder will see its block included on-chain. One final area of competition between builders is through block subsidies. At least five builders on Ethereum appear to be proposing blocks with a higher bid than block reward value, suggesting that these builders are subsidizing their blocks in some fashion. Among the top 10 block builders by number of blocks proposed daily, four builders subsidize their blocks.

The BloXroute builder can sustainably subsidize their blocks using earnings from other business revenue streams, according to BloXroute founder Uri Klarman. Builder 0x69 appears to be subsidizing their blocks as a temporary means to encourage more bundle flow from searchers and establish trusted relationships with searchers. Another explanation may be that certain block subsidies are made possible through direct payments from searchers to builders for bundle inclusion that is not captured on-chain.

The prevalence of block subsidies has helped certain builders such as Builder0x69 and BloXroute outperform other builders. However, it is ultimately the combination of multiple factors that ultimately determine builder profitability. Over the past week, the top two most profitable block builders on Ethereum, Flashbots and beaver.build, which collectively landed more than 16,000 blocks on-chain, did so without the use of any subsidies.

Relays

Diving deeper into the competitive dynamics of builders, it is important to consider the fact that several builders like Flashbots also operate their own MEV relays. Despite there being little to no financial incentives for businesses to run their own relays, the number of relay operators has only grown since the switch to PoS. As background, relays are the off-chain marketplaces where builders participate in a blind auction to sell their blocks to validators. Most operators do not earn a revenue from their relay operations, in part because the first entity to build an open source, permissionless, and performant relay provided the service for free and as a public good.

Flashbots is a venture-backed business that has built and operated MEV-related infrastructure on Ethereum for several years. Given that the most popular relay today remains operated by research and development organization Flashbots, it is uneconomical for most relays to operate a performant and competitive relay for a fee. However, BloXroute, a blockchain infrastructure company that also operates and subsidizes its own builder, is one of the few that charges for their relay services. Most others, including Blocknative, Relayooor, Agnostic, and Ultrasound do not.

The motivation for running a relay

The motivation for entities to launch a relay may be rooted in raising their brand awareness and helping the MEV landscape on Ethereum become more decentralized. Builder 0x69 said in a post on Discord that their goal with launching the relayooor relay was to “have at least 1 completely open sourced non-censoring permission-less (for builders) relay” operating on Ethereum. But with the emergence of two additional relays just like it, Builder 0x69 added that relayooor would likely be sunset by the next Ethereum network upgrade. Promoting a diversity in the number of relays is beneficial to the health of Ethereum. A diversity of relays ensures that potential bugs in software of any one relay does not meaningfully prevent validators from earning MEV, as they can switch to using other relays easily. This is the same rationale for promoting client diversity on Ethereum.

The core of what MEV-Boost software enables is the ability for a validator to connect to more than one relay and thereby discourage overreliance on one MEV infrastructure provider. Optionality when it comes to relays is an especially important feature from the perspective of validators given that before the Merge, the only relay that miners used to earn MEV by operating MEV-Geth software was the Flashbots relay. The Flashbots relay censors transactions to comply with U.S. sanctions. As of December 2022, there are 10 relays on Ethereum, six of which are not censoring user transactions. Among the six non-censoring relays, which include Agnostic, Ultrasound, Relayoor, Bloxroute Ethical, Bloxroute Max Profit, and Manifold, five are not permissioned, meaning any builder can submit blocks to the relay. The only non-censoring relay that is permissioned and requires builders to be whitelisted before submitting blocks is Bloxroute Ethical. Bloxroute Ethical intentionally rejects blocks from builders detected to source transactions from private order flow for the purposes of offering users a more “ethical” relay alternative. The Flashbots relay, which is a censoring and unpermissioned relay, dominates as the most popular relay, winning the highest number of blocks. However, their dominance is gradually waning, as depicted by the chart below:

Outside of altruistic reasons, builders may choose to operate their own performant relay so that their blocks can reach validators faster than otherwise possible. Permissionless relays that accept blocks from any builder must simulate each block proposed by a builder to ensure that the blocks submitted are valid. This creates some amount of latency in the blind auction hosted on permissionless relays. Trusted builders of a relay that are whitelisted and whose blocks do not need to be checked can be fast-tracked through the block bidding process, which is why certain builders may choose to vertically integrate their MEV operations and operate their own relay.

The costs of running a relay

The costs of operating a relay can differ drastically depending on how performant a relay is. For example, relays that are permissionless, opening themselves up to more builders, and therefore, potentially more profitable MEV blocks, need to set-up guard rails against denial-of-service attacks and spam protection. In addition, performant relays that try to minimize the amount of latency when sending blocks to validators on Ethereum must set up multiple servers that can handle variable load conditions and maintain a high bandwidth network. This is especially true given that relays must simulate blocks submitted by third-party or non-whitelisted builders to ensure they are valid and re-register all validators connecting to their relay every epoch. These costs for operating a performant and competitive relay can be several thousands of dollars per month, if not upwards of $100,000/month. However, not all relays optimize for performance, especially the ones that are funded as a public good.

Aside from the differences in each relay’s technical capabilities and capacity, relays (like builders) are differentiated by their reputation. The greatest competitive advantages for a relay are uptime, reliability, and a proven track record for processing blocks fairly between builders and validators. Relays are in a unique position within the MEV supply chain on Ethereum as the infrastructure that can reveal secret information about blocks and their contents before a validator proposes it on-chain. Therefore, builders and validators must trust that a relay operator will not act maliciously. A malicious relay operator could potentially introduce modifications to the original relay specifications published by Flashbots that allows them to front-run the block bids of other builders. To improve trust in relays, most relay operators open source their software and create public endpoints for anyone to monitor the activity of their relay in real-time.

BloXroute’s MEV relay notably reported failures a few days after the activation of the Merge, which caused validators to miss roughly 88 block proposals on the network. BloXroute reimbursed validators for lost funds due to their temporary relay malfunction. The reimbursement of validators was a controversial decision that is viewed by other relay operators like Blocknative as creating “negative economics.” Based on the costs of running a performant relay that competes with the Flashbots relay, which is operated at zero cost to users, and the expectation of reimbursing users for relay failures, there does not appear to be strong incentives for relay operators to build performant relays. Indeed, despite most major staking pools on Ethereum connecting to multiple relays, the Flashbots relay usually dominates as the relay proposing the highest number of blocks ahead of other relays. Therefore, competition between relays, much like the competition between builders (which are themselves searchers to an extent), may decline over time and result in centralization.

Validators

Validators on Ethereum earn a passive income. Beyond their initial deposit of 32 ETH and software configurations, validators have little room for further optimizations to materially increase their rewards, which is by design. If expending more electricity or using expensive and specialized hardware did impact validator rewards, then the competition between validators would result in specialization and potentially centralization. The goal, as stated by founder of Ethereum Vitalik Buterin, is for validators to remain “as dumb as possible.”

One of the critiques of MEV-Boost is that by reducing the risk of specialization and centralization among validators, the network offloads this risk to third-party builders. Flashbots and Ethereum core developers argue that the risk being contained to entities that are not directly interacting with the protocol of Ethereum is marginally better than with validators. However, the incentives for centralization among builders still result in the same concerns of MEV rewards becoming concentrated to a small group of sophisticated actors that can then exert their influence on Ethereum through amassing a larger supply of ETH. In the next section of this report, solutions to the concern around builder centralization will be discussed in detail.

While there is minimal opportunity for specialization when operating a validator, there is when it comes to staking pools. Staking pools are entities that operate validators on behalf of individuals. There are several advantages to staking through a pool rather than setting up an independent validator. For more details around validator pools on Ethereum, read this Galaxy Research report. The entities that are most equipped to offer staking services are often cryptocurrency exchanges, as they already custody and deploy capital on behalf of individuals.

From the perspective of exchanges, offering staking services is an easy way to incentivize users to keep their assets held on their platform for longer periods of time by offering users yield on their deposits. Most staking pools also offer users the ability to stake less than 32 ETH and provide some level of insurance against failures in a validator’s technical set-up. The second and third largest staking entities on Ethereum are exchanges.

The first largest staking entity is Lido, a liquid staking service provider. Liquid staking derivatives (LSD) are assets representing staked ETH that can be freely traded and transacted on Ethereum. Users often rehypothecate their LSD into decentralized finance (DeFi) applications such as Aave to earn additional yield. The Index Coop protocol offers users a derivative asset known as icETH, which automatically earns yield from staked ETH rehypothecated into Aave and then is used to procure more staked ether. At times, the yield from Index Coop is nearly double the yield from regular staked ETH.

Lucrative earnings from rehypothecating staked ETH puts liquid staking service providers at a competitive advantage to individual stakers and regular staking pools in terms of adoption. However, among liquid staking service providers, the competitive landscape is best characterized as “winner takes all.” Even though there are other liquid staking providers, none are as popular as Lido because Lido’s stETH token has amassed the highest amount of liquidity in the DeFi markets. The deep liquidity of stETH is in part due to key integrations with major DeFi protocols like Curve and Yearn Finance. Alternatives to stETH often trade at a steeper discount to ETH due to greater technological or regulatory risks and have not historically offered as high returns as stETH. Contrary to past trends, new staking protocols like Frax Finance deploy a two-token model to allow users to earn above-average yields. Outside of centralized exchanges, the only other entity that is best suited to compete as a staking pool are the services that offer LSDs to users and among those that do, the LSD protocol that boasts the highest amount of market depth.

The problem of relay censorship

The MEV supply chain on Ethereum post-Merge remains vulnerable to regulatory capture because of the overreliance on Flashbots products such as the Flashbots relay. More than 60% of all blocks published on Ethereum are built through the Flashbots relay and therefore enforce censoring behavior of user transactions. In addition to other censoring relays such as Bloxroute’s “Regulated” Relay, the percentage of blocks censoring user transactions is roughly 70%.

There has been gradual improvement to the number of non-censoring relays operating on Ethereum since the Merge and the activation of MEV-Boost software. In November 2022, three new operators— Gnosis, Ultrasound Money, and Builder 0x69—launched their own relay infrastructure to improve the censorship resistance of Ethereum. However, the dominance of the Flashbots relay has not declined materially because of the emergence of other new relays as the Flashbots relay since its launch has maintained a pristine track record of near perfect uptime and boasts free, permissionless features, meaning validators and builders do not have to pay or be whitelisted to connect to the relay. As mentioned, reliability is one of the most important competitive features of a relay, which is why the longer the Flashbots relay remains running without disruption, the more it will become ossified as one of the relays that all validators trust and connect to using MEV-Boost.

Ethereum core developers and the Flashbots team view relay censorship as a somewhat short-term issue because, even if relay diversification does not improve, there is a plan to remove relays entirely from the MEV supply chain. The full vision of PBS, which inspired MEV-Boost, enshrines the role of relays into the protocol of Ethereum.

Enshrined PBS

Enshrined proposer builder separation, sometimes called in-protocol PBS, was the original motivation for building MEV-Boost as an interim solution to mitigating the centralizing impacts of MEV on Ethereum post-Merge. The implementation of enshrined PBS is an active area of research among Ethereum core developers, alongside other ongoing important protocol-level changes focused on scalability and state growth such as such as danksharding and state expiry, respectively. One of the core challenges of PBS is designing a way to facilitate block auctions in a decentralized way. Enshrined PBS would require the Ethereum protocol to create and record a canonical list of block bids from builders and ensure that validators receive their payment from builder after they have executed the builder’s block on-chain.

The original proposal for enshrined PBS, written by Vitalik Buterin in June 2021, offers two different ideas for implementation. The first suggests builders publish a portion of the block they have created first to the chain, along with their payment to the proposer and a cryptographic signature verifying the block as theirs. The validator chosen to propose the next block on Ethereum will then review the list of payments, picking the highest one, and the builder of the winning bundle will then reveal the full contents of the block for the validator to propose.

The second approach is similar but, instead of a validator picking from a list of partial blocks, the validator signs a statement committing themselves to a list of different transaction bundles, offering a higher level of optionality and flexibility to validators in terms of what they can execute on-chain. The second approach requires a new slashing condition that would penalize the validator if they did not propose one of the bundles on their list. Since Buterin’s original proposal, there have been new discussions around alternative paradigms for enshrined PBS such as re-designing the core mechanisms such that the bidding process happens during a single slot instead of two. As background, a slot is a unit of time on the Beacon Chain lasting 12 seconds. During these 12 seconds, a block can be proposed by a validator.

Phil Daian, founder of Flashbots, has also offered an idea for a “light” version of enshrined PBS where validators and builders do not participate in a block auction at all. Instead, validators pick the most profitable payment from a builder through the creation of a new transaction type. The new transaction type would transfer rights to the data availability of a block to the chosen builder.

Protocol-enforced proposer commitments (PEPC)

In contrast to enshrined PBS, Ethereum developers are considering another possible framework for enabling block auctions in-protocol. Called protocol-enforced proposer commitments (PEPC) this framework attempts to generalize the allocation mechanism for block rewards by letting the validator enforce more complex rules around how their block is made, i.e. enforce restrictions on gas use, limit the use of block space, communicate a list of state accesses, and dictate compatibility of transaction flows. EigenLayer is a smart contract protocol currently under development that may act as the testing grounds for PEPC and other experimentation related to applying additional slashing conditions to validators.

The EigenLayer protocol enables validators to earn additional yield on their staked ETH by re-staking it into Ethereum, other applications, and alternative blockchain protocols. There are two modes of re-staking envisioned on EigenLayer: native re-staking through updating validator withdrawal credentials and liquid re-staking by depositing liquid staking derivative tokens into EigenLayer smart contracts. Re-staking through EigenLayer smart contracts is made possible through the enforcement of additional slashing conditions on validators. Depending on the middleware and rules that a validator opts into through the EigenLayer protocol, there are additional penalties for misbehavior that minimizes the dangers of stake rehypothecation to the security of Ethereum.

EigenLayer is expected to launch its re-staking services sometime in 2023. In the first phase of its launch, EigenLayer will only allow validators to opt into a curated set of re-staking middlewares. For example, validators will be able to re-stake to the Eigen Data Availability layer which is envisioned to service Layer-2 rollups like Arbitrum and Optimism with a highly customizable and hyper-scalable data availability service. However, over time, the vision is to enable permissionless innovation on EigenLayer and empower users to create and launch their own re-staking middlewares. One of the re-staking middlewares that could in theory be developed on EigenLayer down the road are partial block auctions.

Under MEV-Boost and the use of relays, validators cannot insert their own transactions into a block built by a third-party builder as they do not see the contents of a block before it is proposed on-chain. Relays only reveal the block headers and rewards to validators. Only after the validator has committed to a specific block by signing the block header will the relay send back the full contents of a block for the validator to propose on-chain. This is to ensure that validators cannot front run builders by seeing the contents of a block and re-building it themselves. However, if additional slashing rules were imposed on validators through EigenLayer for front running builders, there is a stronger guarantee that a builder’s portion of the block gets included correctly at the beginning of the block or otherwise the re-staked validator would face severe slashing penalties.

The EigenLayer protocol would act as the middleware software to facilitate the bidding process between a builder and a validator for the partial block space. This is an important capability that would eliminate the concerns around relay censorship and ensure the censorship resistant qualities of Ethereum are reinforced by giving back the ability of validators to propose transactions for inclusion in a block. In addition, the long-term vision for EigenLayer enabling a whole suite of re-staking middleware and slashing primitives is foundational to the research for PEPC. Many components of PEPC will be tested through the development of EigenLayer like how the core principles behind PBS are presently being tested through MEV-Boost in advance of in-protocol PBS.

Both enshrined PBS and PEPC are still likely years away from implementation. Further research is needed about the complexities of both in-protocol solutions and relevant third-order consequences on validator behavior. In addition to further research, there are other protocol-level upgrades that target improvements to Ethereum’s virtual machine and scalability that will likely take precedence now that the Merge is over. However, until an in-protocol solution for MEV block auctions is ready, the risk of relays front-running builders will exist. To mitigate that risk, a diversity of relays in the short-term is important, as are other interim solutions either through new smart contract protocols like EigenLayer or alternative network-level solutions like the shutterized beacon chain concept. As background, the shutterized beacon chain ideated by Gnosis CEO Martin Köppelmann proposes optionally encrypting user transactions through distributed key generation such that the content of transactions is not revealed until after they are included on-chain. A proof-of-concept for the shutterized beacon chain is expected to be implemented on the Gnosis Chain later this year in 2023.

The problem of block builder centralization

Outside of relay censorship, there is a concern that block building will become centralized to a few specialized entities. As background, validators on Ethereum are responsible for building, proposing, and validating blocks. Validators have the privileged position of ordering, re-ordering, censoring, and inserting transaction into blocks. Building profitable blocks is a resource-intensive activity as block builders have a short amount of time, roughly 12 seconds, to run through several different simulations of blocks to identify the one maximizing block rewards. Leaving the resource-intensive and highly optimizable activity of block building to validators post-Merge naturally gives an edge to large, sophisticated staking pools over independent validators as the former can invest in the best block building solutions while the latter cannot. Therefore, to prevent MEV from becoming a centralizing force on Ethereum, MEV-Boost separates the activity of block building from validators, who are the block proposers under PoS. Under the PBS model, validators no matter if they are operated by a large staking pool or an independent node operator can all outsource the responsibility of building a profitable block containing MEV rewards to a third-party block builder. In this way, centralization of MEV rewards to large staking entities are avoided post-Merge.

However, outsourcing the activity of block building to third-party block builders means that there is still the potential for the block builder market to become centralized. While this is a better alternative than validators becoming centralized because of MEV, it is still not ideal and creates the risk of regulatory capture at a high-level of the MEV supply chain. To mitigate the negative externalities of builder centralization, Flashbots has released minor tweaks to MEV-Boost software in recent months, the most notable of which enables validators to set a minimum bid on the blocks they receive from relays. By setting a minimum bid above zero, a validator node operator can automatically build blocks locally from the Ethereum mempool if the rewards from a block built by a third-party builder does not exceed a certain threshold. In addition to the minimum bid value, Ethereum core developers are working on a tweak to the Ethereum Engine API to help validators more easily compare the rewards from a locally built block and a block built by a third-party builder.

As of December 31, 2022, 75% of MEV-Boost blocks are built by the Flashbots builder. Through competition, the dominance of the Flashbots builder is waning gradually. The percentage of blocks built by pseudonymous builders increased from less than 10% in September 2022 to close to 50% as of the end of December 2022.

Outside of increased builder competition, there are a few other solutions being discussed by Ethereum core developers and the Flashbots team to address the negative externalities of block builder centralization.

crLists

The first and simplest solution is censorship resistance lists (crLists). This is an idea that has been discussed by Ethereum core developers since as early as January 2022. It proposes a list of transactions that third-party block builders must include in their construction of a block. This ensures that even if the block building market does become centralized, builders do not have the power to censor transactions and thereby degrade the credible neutrality of the Ethereum by building regulatory compliant blocks. Using crLists, validators would be able to enforce the inclusion of a list of transactions from the public mempool that block builders must accept into their block. In terms of implementation, crLists are not difficult. Robert Miller, product lead at Flashbots, said during a podcast that crLists could be implemented in as little as 2 to 3 months if there was enough consensus among Ethereum core developers to work on the code change. However, there is little to no consensus among developers to enforce crLists on a protocol-level as some believe crLists are too short-term of a solution to the problem of builder centralization. Some developers argue that tackling the root of the problem by decentralizing the role of the builder rather than implementing crLists would be the more effective solution.

Collaborative block building

There is ongoing research on how to redesign the core responsibilities of a builder such that multiple builders collaborate to create a single block. Builders rely on highly specialized algorithms for combining transaction bundles from searchers and the local mempool in a profitable and competitive way. Instead of a builder using their proprietary technology to build a full block, there is the possibility of multiple builders running their algorithms to collaboratively build a block such that the combination of different transaction bundle aggregation techniques results in a more profitable block than if a builder had not collaborated with other builders and built their own block in isolation. This would only be possible if builders could run their algorithms in isolation from other builders and some how seal the contents of their partial block from other builders so that other builders do not steal their MEV. Through the development of decentralized computing and hardware, it may become possible for several independent builders to pool together resources for block construction without revealing sensitive information. Discussions around breaking up the responsibilities of block builders often rely on the use of advanced cryptography such as zero knowledge and polynomial commitments. In comparison to crLists, the ways to decentralize block builders is a less defined and developed area of research.

SUAVE

Flashbots is actively working on a solution to decentralize the role of block builders through collaborative block building. The project is called the Single Unifying Auction for Value Expression (SUAVE). SUAVE was unveiled on October 14 during Devcon, an annual Ethereum developer conference, by Phil Daian, cofounder of Flashbots. Daian described it then as an MEV-aware encrypted mempool for returning MEV profits back to the end-user. In late November, Flashbots published a blog post titled, “The Future of MEV is SUAVE,” revealing more details around the project. The blog described SUAVE as an independent blockchain network that can be used to extract cross-chain MEV. “Importantly, SUAVE goes beyond sequencing for a single blockchain. We designed SUAVE to be the mempool and block builder for all blockchains,” the post reads.

Today, technical details around how SUAVE would work are scant. The information currently available around SUAVE illustrates the framework of thinking that will inspire the architecture of the product, rather than detailing the architecture of SUAVE itself. In theory, SUAVE will be a blockchain that is able to accept expressions of user preference from multiple blockchains and then assist a decentralized network of block builders to trustlessly propose blocks to each of these networks. The SUAVE Chain will be composed of three main components: a universal preference environment, an optimal execution market, and a decentralized block building network.

The preference environment is envisioned to be as flexible as possible, meaning that users should be able to express their preferences not only about MEV, but any type of transaction ordering or placement within a block. This preference will be associated with a bid contract, where the users will lock up a certain amount of ETH to incentivize the execution of their stated preference, which again can be as complex as signaling for the state of a blockchain to be Y or as simple as signaling for transaction X to be included in the next block of a blockchain.

Preferences are then passed on to the execution market where actors called executors compete to offer the best execution of user preferences as possible. Today, builders can be thought of as the executors of searcher bids. On the SUAVE chain, executors will process a variety of transaction preferences in exchange for the ETH locked by a user in the preference market. The final piece of the SUAVE chain is the decentralized builder market. The details around the decentralized builder market are the sparsest out of three. At a high-level, the SUAVE chain will enable blocks to be built collaboratively between builders using secure enclaves to protect block content privacy.

Executors will listen to the preference market and run algorithms for merging different user preferences and searcher transaction bundles within a block. These blocks will be iteratively improved on and gossiped between executors such that the final block has been enriched with multiple executor contributions. In this way, while SUAVE’s decentralized block building network may introduce more latency into the process of block building, it may also result in more valuable blocks because the blocks produced benefits from many builders and block building algorithms.

To ensure that user preferences aren’t leaked in the process of block buildings, builders will be required to run their transaction ordering algorithms within a secure enclave, which refers to an isolated computation environment for processing code and data on a computer. Historically, there have been hardware-related exploits involving the use of secure enclaves, which is why their use in SUAVE may pose a security risk. Flashbots has said they are exploring alternatives to secure enclaves, including trusted execution environments, fully homomorphic encryption, threshold encryption, and multi-party computation. However, based on the readiness of technology that is available today, secure enclaves are the best short-term solution to facilitating decentralized block building in the next 3 to 6 months, according to Flashbots. The full vision for SUAVE, which would support all three components explained above, will likely not be ready for implementation for years.

Flashbots has talked a big game about SUAVE, but today very few details have been made public. Some notable aspects of SUAVE design that remain unclear include:

Cross-domain blocks space auctions. It is unclear how the SUAVE chain will be able to support cross-domain block space auctions and plug into other alternative Layer-1 blockchains.For the bidding contracts in the preference market to be denominated and paid in ETH, the SUAVE chain will require users to bridge their assets but details around the architecture of such a bridge are unclear. However, a recent proposal on the Flashbots forum alternatively suggests building SUAVE as a Layer-2 rollup on Ethereum, as opposed to a Layer-1 blockchain, which would mitigate bridging risk.

User kickbacks. At this time, the exact mechanisms through which users will receive kickbacks on MEV extracted from their transactions remains unclear, though this will reportedly be the first part of SUAVE that is implemented.

Use of secure enclaves. It is also unclear how exactly SUAVE will use secure enclaves to decentralize the role of the block builder, as SUAVE may allow executors to host their own enclaves on their own devices or may require executors to use a trusted cloud hosting solution.

Closely intertwined with the research highlighted above on mitigating builder centralization, developers from Flashbots and the Ethereum Foundation are monitoring and discussing solutions for several other areas of MEV such as:

Improving user transaction privacy. Sometimes referred to as programmable privacy, developers are actively researching ways to lower the barriers to cooperation between builders by enhancing privacy guarantees over user transactions.

MEV accrual to end-users. The current MEV supply chain on Ethereum ensures that the majority of value accrual from MEV goes to the block proposer, that is the validator on Ethereum, which may incentivize validator collusion. MEV smoothing is another area of research among Ethereum core developers that attempts to minimize block reward variance from MEV and discourage validator collusion.

Cross-chain MEV. There is also renewed interest in how MEV-mitigating strategies on alternative Layer-1 blockchains such as Cosmos will interact with those developed on Ethereum, especially given trends of rising decentralized finance activity on other chains.

Conclusion

MEV-Boost has enabled the early beginnings of a more decentralized MEV supply chain, where several different entities can participate as a searcher, builder, validator, or relay. The dominance of Flashbots should be considered a depiction of Ethereum’s status quo before the Merge, which will take time to move away from. Despite initial concerns over network censorship and builder centralization, early data about MEV on Ethereum since the Merge suggests that competition among builders is thriving and a diversity of agnostic and censorship resistant relays is slowly chipping away at the dominance of the Flashbots relay. However, due to the lack of robust incentives to encourage competition among searchers, builders, and relays, there is a concern that the MEV supply chain becomes dominated by a few knowledgeable stakeholders.

Flashbots as an organization continues to work towards MEV democratization by subsidizing other relays and open sourcing their strategies for being an effective relay and builder on Ethereum. Ethereum developers and researchers are researching ways to remove the trusted relay setup required to connect builder to validators. However, there are several open questions related to implementing enshrined PBS and Ethereum core developers are likely to prioritize other major upgrades to the Ethereum protocol such as proto-danksharding ahead of PBS implementation. Therefore, the Flashbots team and other new entities in the MEV supply chain are working towards further optimizing builder and relay technology to be more resilient and efficient.

The concern around builder centralization, while not a reality, is still a likely possibility, especially if DeFi activity pick up and MEV earnings become more lucrative. Therefore, there are several solutions for implementation in the interim that developers are pursuing, namely SUAVE and partial block auctions through smart contract protocols like EigenLayer. Ethereum developers are inching closer to solving the “millennium prize problem of crypto,” that is MEV, but there is still much work to be done before the negative externalities of MEV can be considered neutralized. While Flashbots is spearheading a large portion of this work, the open sourcing of MEV infrastructure is envisioned to diversify the number of stakeholders involved. This is likely to increase the amount of funding and innovation going forward and increase the chances of DeFi on Ethereum becoming a fairer environment for trade than traditional finance.

Legal Disclosure:

This document, and the information contained herein, has been provided to you by Galaxy Digital Holdings LP and its affiliates (“Galaxy Digital”) solely for informational purposes. This document may not be reproduced or redistributed in whole or in part, in any format, without the express written approval of Galaxy Digital. Neither the information, nor any opinion contained in this document, constitutes an offer to buy or sell, or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell, any advisory services, securities, futures, options or other financial instruments or to participate in any advisory services or trading strategy. Nothing contained in this document constitutes investment, legal or tax advice or is an endorsement of any of the stablecoins mentioned herein. You should make your own investigations and evaluations of the information herein. Any decisions based on information contained in this document are the sole responsibility of the reader. Certain statements in this document reflect Galaxy Digital’s views, estimates, opinions or predictions (which may be based on proprietary models and assumptions, including, in particular, Galaxy Digital’s views on the current and future market for certain digital assets), and there is no guarantee that these views, estimates, opinions or predictions are currently accurate or that they will be ultimately realized. To the extent these assumptions or models are not correct or circumstances change, the actual performance may vary substantially from, and be less than, the estimates included herein. None of Galaxy Digital nor any of its affiliates, shareholders, partners, members, directors, officers, management, employees or representatives makes any representation or warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy or completeness of any of the information or any other information (whether communicated in written or oral form) transmitted or made available to you. Each of the aforementioned parties expressly disclaims any and all liability relating to or resulting from the use of this information. Certain information contained herein (including financial information) has been obtained from published and non-published sources. Such information has not been independently verified by Galaxy Digital and, Galaxy Digital, does not assume responsibility for the accuracy of such information. Affiliates of Galaxy Digital may have owned or may own investments in some of the digital assets and protocols discussed in this document. Except where otherwise indicated, the information in this document is based on matters as they exist as of the date of preparation and not as of any future date, and will not be updated or otherwise revised to reflect information that subsequently becomes available, or circumstances existing or changes occurring after the date hereof. This document provides links to other Websites that we think might be of interest to you. Please note that when you click on one of these links, you may be moving to a provider’s website that is not associated with Galaxy Digital. These linked sites and their providers are not controlled by us, and we are not responsible for the contents or the proper operation of any linked site. The inclusion of any link does not imply our endorsement or our adoption of the statements therein. We encourage you to read the terms of use and privacy statements of these linked sites as their policies may differ from ours. The foregoing does not constitute a “research report” as defined by FINRA Rule 2241 or a “debt research report” as defined by FINRA Rule 2242 and was not prepared by Galaxy Digital Partners LLC. For all inquiries, please email contact@galaxydigital.io. ©Copyright Galaxy Digital Holdings LP 2022. All rights reserved.