This report explores dollar-pegged stablecoins, providing a comprehensive overview of their evolution over time. It covers the major stablecoins in existence today and explains the designs and stability mechanisms used, details the competitive dynamics of each type, and analyzes their stability and usage. We provide a risk assessment framework for evaluating the many stablecoins available in today’s market and share our outlook for how stablecoins will progress.

Key Takeaways

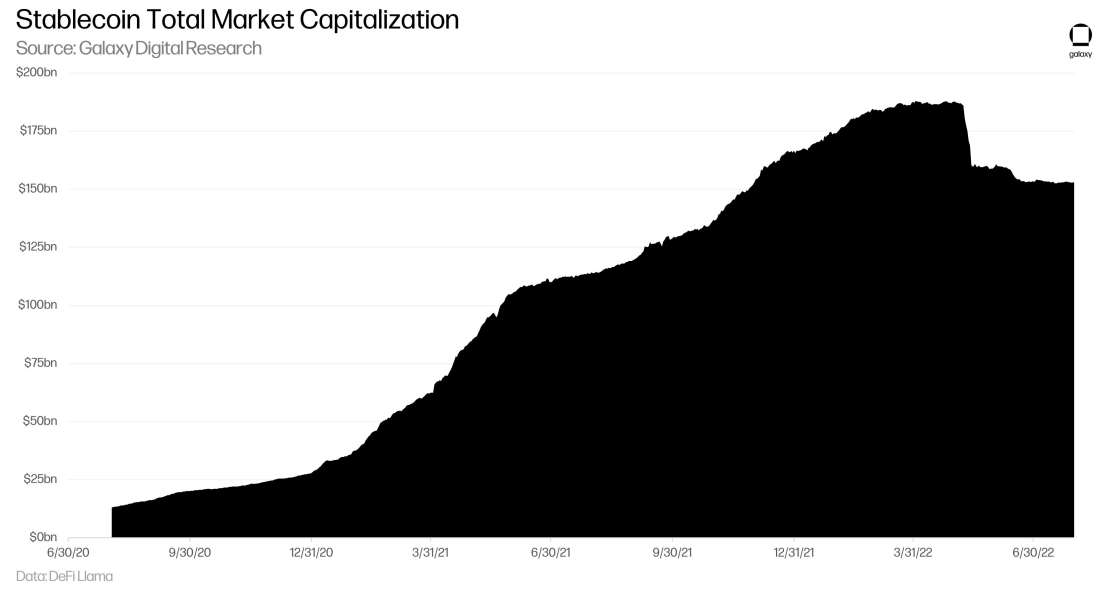

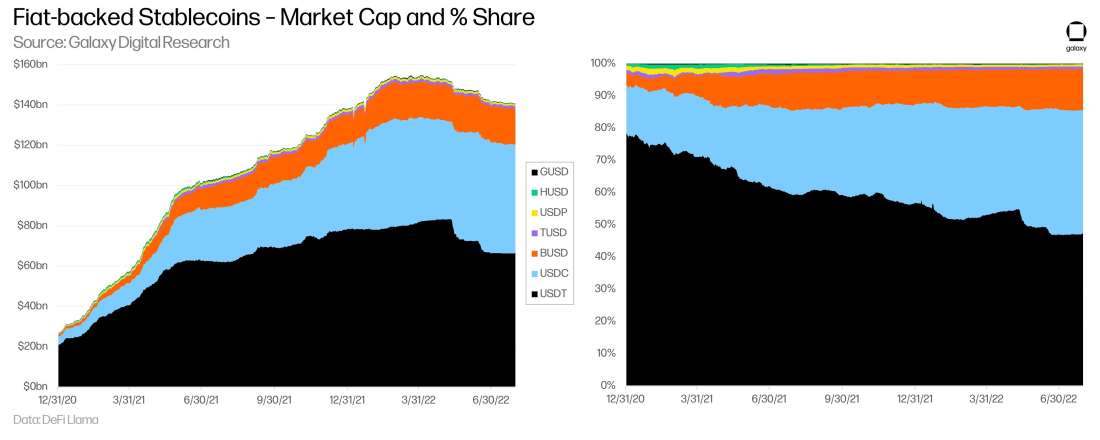

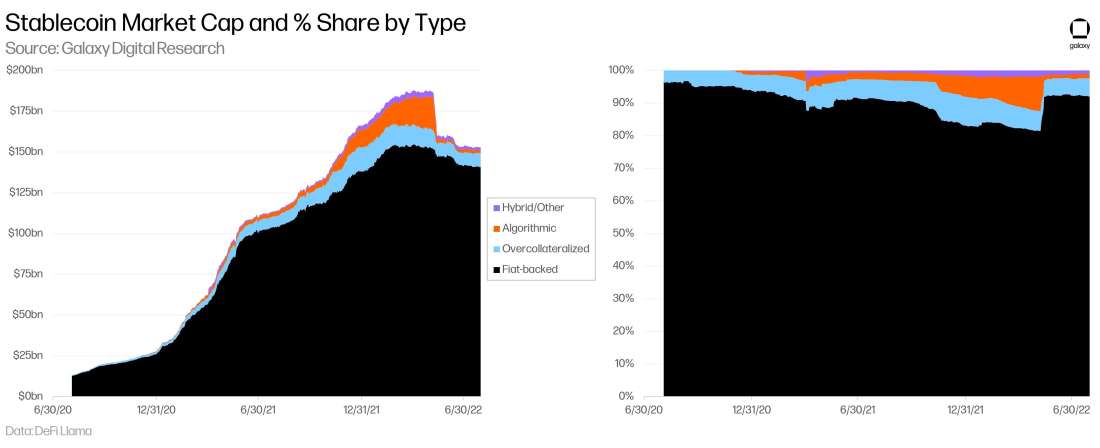

At a $150bn+ market cap, stablecoins have become an increasingly important part of the crypto economy

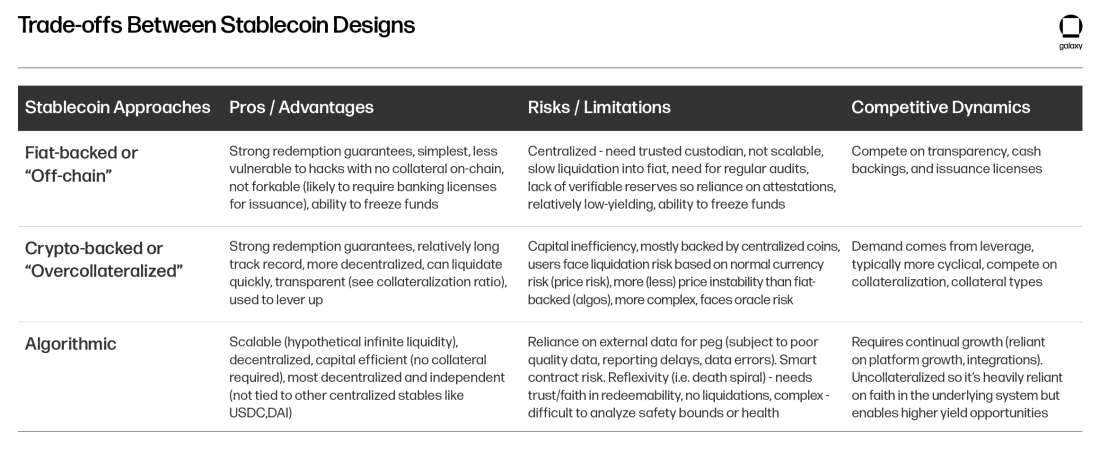

Stablecoin designs largely fall into 3 main categories (fiat-backed, overcollateralized, and algorithmic) – each of which comes with different advantages/shortfalls, stability mechanisms, and competitive dynamics

Tether, the long-standing leading stablecoin by market value and volume, has endured a long history of criticisms but its market dominance has eroded rapidly in recent months, mostly to the benefit of Circle’s USDC

MakerDAO’s DAI has emerged as the leader among “decentralized” stablecoins, but its current form has deviated significantly from its original vision as it has become significantly reliant on USDC for stability, leaving much to be desired

The collapse of Terra USD (and all the failures of other algorithmic stablecoins before it) has led most protocols or platforms behind algorithmic stablecoins to fundamentally alter their designs to more collateralized models

On-chain transaction data and price histories provide meaningful insights to assess the resilience and usage of each type

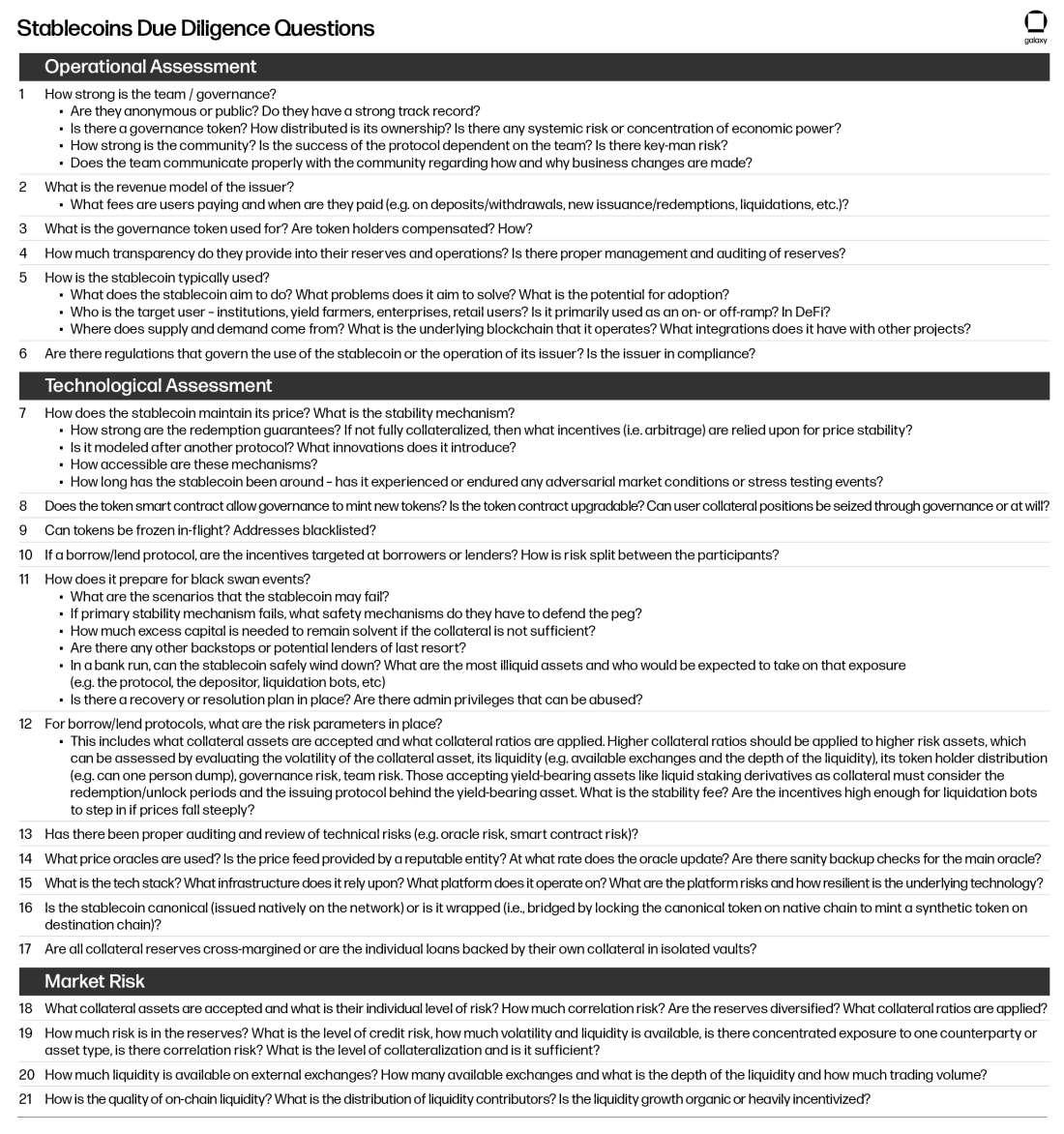

New stablecoins products continue to emerge with innovative features, but potential users should be prepared with a risk assessment framework while conducting due diligence for each offering

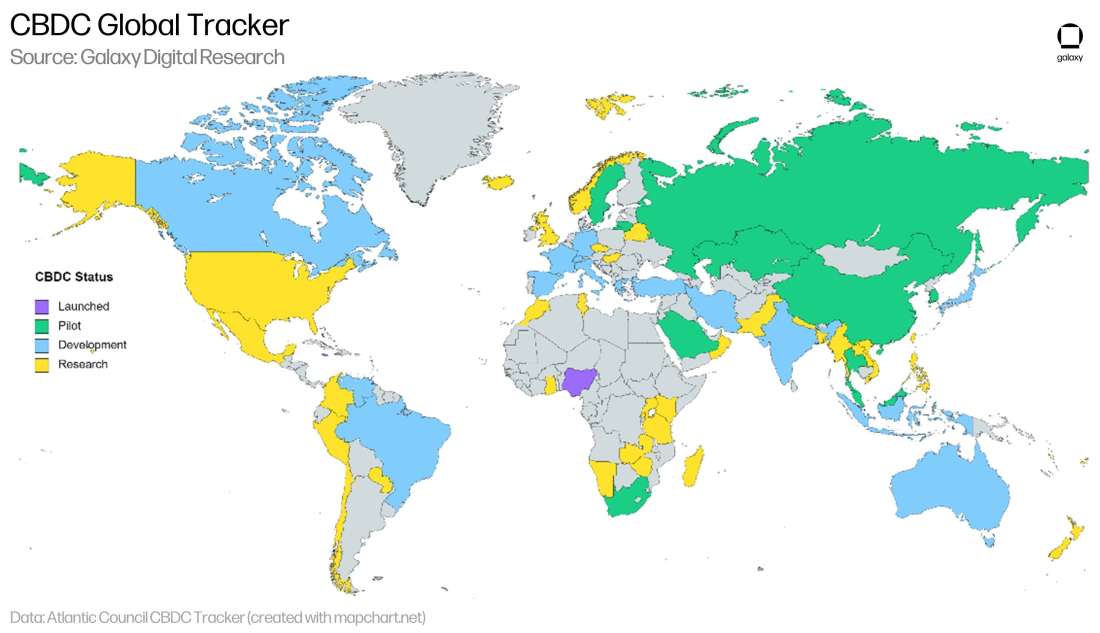

Comprehensive regulatory regimes overseeing stablecoins could soon be established across major global economies, which will have significant consequences for the issuance, redemption, usage, and adoption of stablecoins

Despite recent stablecoin failures and macro headwinds, the evolution of stablecoins is not slowing, and the stablecoins that endure the toughest challenges are likely to gain share and thrive

Introduction

Stablecoins are digital representations of other assets for use on blockchains and in the crypto economy. While stablecoins may also be designed to track the price of other underlying assets such as gold and other exchange-traded commodities, this report will focus on stablecoins linked to the US dollar, the most common use of stablecoins today.

Importance of stablecoins

To some, stablecoins are a boring innovation, especially when they may be looking to escape the perils of the US dollar for a more sound, transparent monetary system as promised by Bitcoin. Stablecoins have the thankless job of maintaining parity to paired assets, where, if successful, there is only downside risk with no potential for price appreciation. Achieving and maintaining parity with another asset has been an exercise in innovation for hundreds of years—more recently, the age of tokenization has yielded many approaches, both successful and unsuccessful. While there is a continuously growing graveyard of failed experiments, there are also bright spots. The reality is that stablecoins are important bridges connecting the digital and physical worlds that serve important functions in the crypto economy and help facilitate the adoption of blockchains. Stablecoins combine the benefits of the open crypto economy with the price stability of widely accepted fiat currencies and have the potential to transform the way that people and businesses use money.

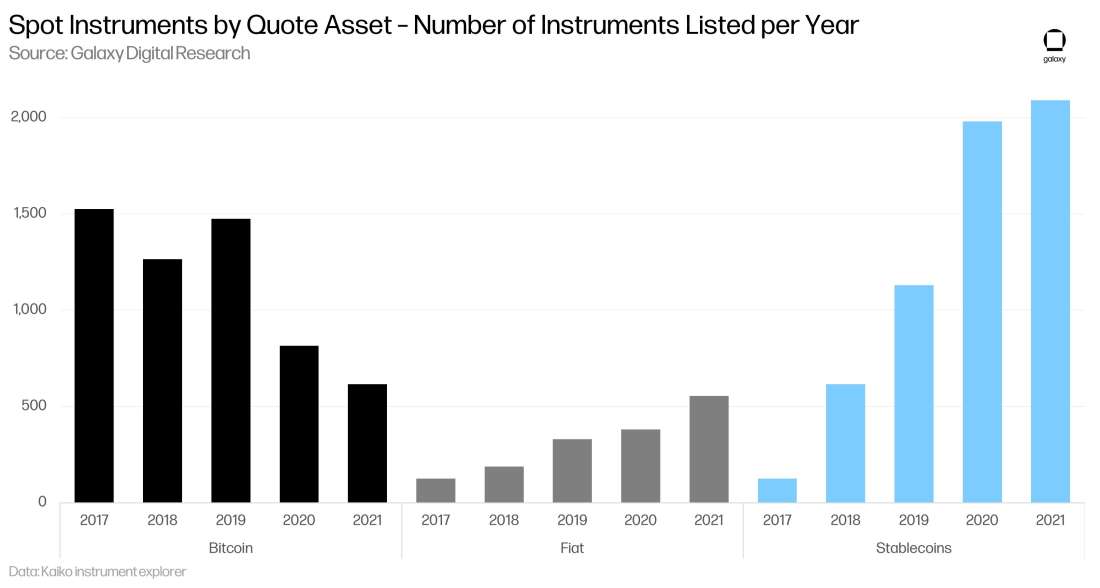

As money, stablecoins address many of the long-standing pain points associated with crypto. The effective ones are stable, global, easy to transfer, and storable in non-custodial wallets, making it simple for anyone to use them without a bank account. While unbanked payments uses are still nascent, stablecoins are heavily used for crypto trading today. In the early days of the crypto economy, most trading pairs were denominated in BTC, but this wasn’t ideal given bitcoin’s high price volatility. The creation of Tether, the first stablecoin, enabled quick and easy trade settlement in dollars and provided a lifeline to crypto exchanges that mostly lacked access to the traditional banking system but wanted to offer pairs based on USD. The shift from BTC to stablecoins for quote pairs has been dramatic over the years, as data from Kaiko illustrates.

Critics often dismiss cryptocurrencies and blockchain because they struggle to see why bitcoin or ether would be used for payments, failing to recognize the merits of the underlying technology. Stablecoins offer a clear and viable use case today, combining the properties of fiat currencies with the enhancements of public blockchains to function as a widely accepted unit of account for pricing assets and as a stable medium of exchange to facilitate payments.

An open financial system provides improvements over the traditional closed financial system through more efficient money movement and data. Compared to traditional payment flows and bank transfers, crypto markets and networks operate 24/7 and can offer a lower-cost alternative that enables instantaneous and borderless settlements leaving more money in the hands of consumers and businesses. Stablecoins can also support financial inclusion in a world where nearly 2bn people, or ~25% of global citizens, are unbanked (and many others underbanked as they lack access to basic financial services). Anyone with a mobile device and an internet connection can leverage US-dollar-backed stablecoins to store and send money. That means the open financial system can be accessed by those who need it the most—including those living in high-inflationary economic regions and those under authoritarian regimes—offering a digital currency that is a better store-of-value than their depreciating restricted local currencies.

Stablecoins adoption has accelerated as the underlying infrastructure of Bitcoin and Ethereum has continued to develop and integrate into the global economy. The explosion of DeFi in recent years has led to even more demand for stablecoins as a tool for leverage, risk management, savings, and other financial activities. Stablecoins are one of the fastest growing asset categories and represent a $150bn+ asset class (~15-20% of the global crypto market cap). Indeed, 3 of the top 6 crypto assets by market capitalization are stablecoins today. The growth of stablecoins as an asset class has outpaced Bitcoin and Ethereum during both the bull market of 2021 and the market correction experienced in 2022.

The different types of stablecoins

Not all stablecoins are the same. Several different types of stablecoins have emerged with different price stability mechanisms. The composition of reserve assets varies considerably across popular stablecoins, with some stablecoins backed entirely by off-chain assets including cash or short-term, highly liquid assets, and others backed by assets significantly less liquid than cash or cash equivalents. Stablecoin design considerations: (i) peg, (ii) collateral, (iii) collateral amount, (iv) mechanisms, (v) price information.

Stablecoin designs can largely be categorized into three main categories:

Fiat-backed (centralized or custodial) stablecoins. As the most popular type of stablecoin, centralized stablecoins follow an IOU model where a central entity backs the value of stablecoin with assets, and the issuer provides a mechanism to create new tokens or redeem existing tokens for underlying collateral on a one-to-one basis.

Overcollateralized, crypto-backed stablecoins. Rather than going through a trusted, centralized issuer, overcollateralized stablecoins are issued through programmable smart contracts typically on non-custodial borrowing/lending protocols where various crypto assets are accepted as collateral and the reserves each stablecoin are always verifiable on-chain.

Algorithmic (undercollateralized) stablecoins. Algo-stables are a newer class of stablecoins that maintain price stability with the help of a separate asset to absorb volatility. Rather than being explicitly backed or fully collateralized, algorithmic stablecoins are designed to maintain price parity with a certain asset through market forces via smart contracts to increase/decrease supply.

These are just the general distinct classifications that we’ve seen to date, but there also exist several stablecoins that exist outside of these categories such as commodity-backed stablecoins that are fully collateralized by physical assets, or, as seen more frequently this past year, stablecoins that fit within multiple categories by combining aspects from both algorithmic and overcollateralized models.

In this report, we explore the different types of stablecoins, profile some of the most prominent stablecoins and their issuers within each category, examine the competitive dynamics that are unique to each approach, summarize the trade-offs between individual stablecoins as well as the different stablecoin categories, highlight some of the key risks facing stablecoins, and analyzing them along key factors.

Fiat-backed Stablecoins

Fiat-backed stablecoins are collateralized by off-chain financial assets and rely upon centralized and regulated entities for the issuance/redemption of units and the custody of reserve assets. Since the composition of reserves are not verifiable on the blockchain, issuers of fiat-backed stablecoins rely on reserve attestations conducted by independent auditors to confirm the existence of reserve assets. Historically, though, these attestations have lacked key details about the components of reserve assets and have been reported infrequently on an end-of-period basis and with a lag. While the frequency and detail of reserve attestations has generally increased over the years, the specificity of these attestations varies across issuers and uncertainty remains in the market due to their opacity.

Issuance of fiat-backed stablecoins is the process of creating new tokens, which requires the issuer to be sufficiently capitalized with liquid assets; issuers mint new digital dollars for their customers for every dollar that they take in. Redemption is the process by which a customer returns tokens to the issuer, thereby removing them from circulation, and receives fiat currency from the issuer in return. Tokens returned to the issuer are either destroyed or placed in the issuer’s treasury for future issuance. Issuance and redemption of fiat-backed stablecoins is available to direct customers of the issuer, usually restricted to institutional clients, which must onboard through robust verification process that includes complete KYC compliance checks.

Stablecoin issuers provide varying levels of guarantees that redemptions of tokens may always be at the rate of $1.00. The issuance and redemption process may also be subject to certain minimum amounts, incur additional fees, and could take several days to process. Stablecoin users who want faster access to liquidity may swap their stablecoin on an exchange or secondary marketplaces (outside of the issuer’s redemption process), which subjects the stablecoin to price risk through supply/demand forces. However, large variances from par typically do not persist if the issuer’s redemption mechanism is believed to be working properly – price deviations present arbitrage opportunities that often see traders step in by buying the stablecoin in the open market at a discount to par so that it can then be redeemed directly with the issuer. Fiat-backed stablecoin issuers typically market themselves based on the quality and composition of their reserves (many committed to 100% cash & cash equivalent backings), the verification of reserve funds, the regulatory licenses they obtain, and the ease at which units can be created and redeemed.

While regulatory standards to oversee stablecoin issuers and their practices have not yet been established by core regulatory bodies or any international standard setters, stablecoin issuers have taken a proactive approach towards expected regulatory compliance as it relates to disclosures, risk management standards, and reserve practices. So, while no stablecoin arrangement is fully regulated, some activities may be (e.g., KYC/AML & counter financing of terrorism (CFT) requirements may call for certain entities to register with FINRA or obtain money transmitter licenses). The lack of proscriptive regulations also means that there can be some leeway that stablecoin issuers to operate as not every issuer required to provide the same redemption guarantees to its holders, particularly relevant when evaluating on-shore vs. off-shore fiat-backed stablecoin issuers.

To illustrate, we compare the two largest issuers of stablecoins: Tether (USDT) and Circle (USDC).

Tether

Formed in 2014, Tether (with a capital T) is the issuer of the largest stablecoin, tether (or USDT). Tether is closely connected with the crypto exchange Bitfinex, sharing the same parent company, iFinex, and is registered in the British Virgin Islands. USDT was originally issued on the Omni Layer Protocol, built on top of Bitcoin, in October 2014, before expanding to other blockchains including Ethereum. In addition to USDT, Tether also issues stablecoins that track EUR, CNH, MXP, and physical gold.

USDT initially found product-market fit as a way for users and exchanges to circumvent the banking system at a time when banks were not willing to support crypto companies and traders. During the 2017 bull market, very few exchanges, even those in the United States, were able to get and maintain bank accounts, and Tether filled that void, providing a token that could be used for USD-denominated trading. USDT is popular offshore, especially in China, where it has been a key part of the workflow for converting fiat to crypto. Due to national regulations prohibiting financial institutions from servicing crypto exchanges, users typically convert their fiat into USDT at an OTC desk before depositing the USDT on an exchange. While this process is somewhat cumbersome, it allows Chinese users to access crypto in a tightly regulated environment and serves as a major source of demand for USDT. Note: While USDT is still available for US persons and business to use, Tether stopped directly serving US individuals and corporate customers since the start of 2018, restricting them from issuance/redeeming services.

Today, USDT is mainly used as an on- and off-ramp as well as in trading pairs for crypto trading across several exchanges. It currently ranks #3 among all cryptocurrencies behind BTC and ETH with a market cap of over $70bn, and is available on 12 blockchains including Tron, Solana, Avalanche, and others.

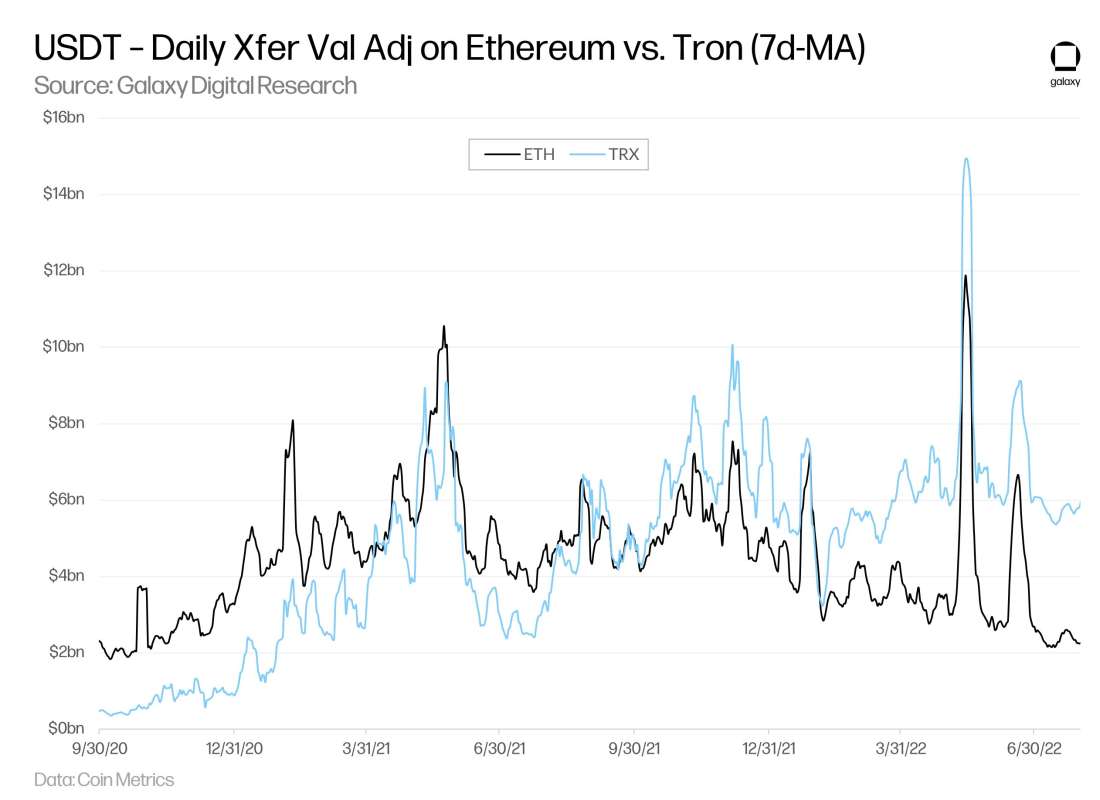

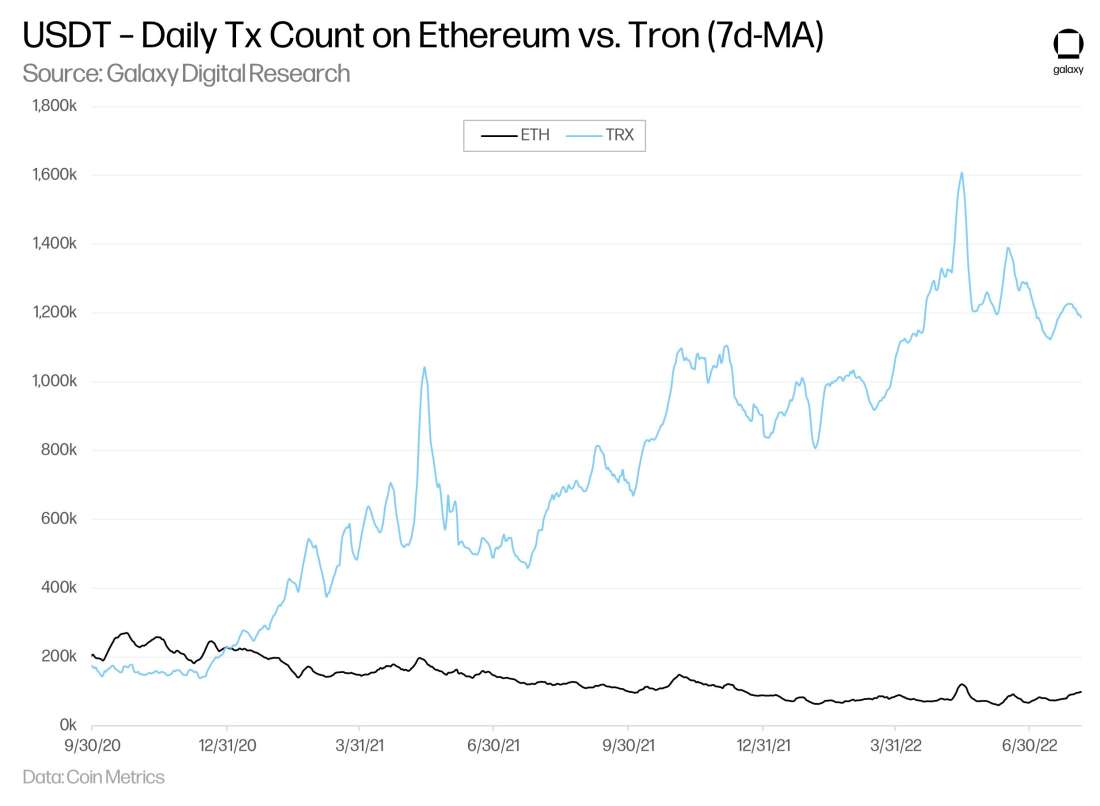

USDT’s presence on Tron is particularly notable. Tron has relatively weak settlement assurances and is generally not viewed as a very secure platform. But as a centralized asset, USDT is only minimally affected by Tron’s poor settlement assurances, and as such is well-suited to take advantage of the lack of congestion on the platform. Specifically, because USDT tokens represent an IOU for assets held in reserve by the centralized Tether Limited entity, and because Tether can freeze and reissue these IOUs at will, there’s no need for the more durable finality offered by Bitcoin or Ethereum. Many of the asset’s core applications are time-sensitive, making them an ideal fit for Tron, which has quick block times and mostly low fees due to less network congestion than Bitcoin or Ethereum. USDT is used as an on-ramp into crypto, a quote currency for spot and derivatives trading, a vector for cross-exchange arbitrage, and an instrument for international dollar-denominated transfers.

Tether’s Controversy and Legal Issues

In the past, critics have often questioned Tether’s operations and the authenticity of its reported reserves. Some of the initial criticisms claimed Tether was printing USDT “out of thin air” as a means to buoy liquid digital asset prices (like BTC) – this theory appears to have been based on dubious data and didn’t hold scrutiny given the growth of Tether issuance coupled with the decline in BTC’s USD-denominated exchange rate. More recent and durable criticism has arisen over the specific assets that are held in its reserves, particularly the non-cash holdings, and whether they are liquid enough to be converted to cash to meet all redemption requests in full and in a timely manner were a bank run scenario to materialize.

In April 2019, New York State Attorney General (NYAG) Letitia James said they were investigating crypto exchange Bitfinex—operated by the same parent company as Tether—alleging that both Bitfinex and Tether defrauded investors “in a cover-up to hide the apparent loss of $850 million of co-mingled client and corporate funds." In February 2021, NYAG’s Letitia James fined parent company iFinex $18.5m and ordered both parties to cease trading activity with New Yorkers after state investigations found that Tether made false statements about having sufficient reserves to back every USDT in circulation. To increase transparency, the court also asked Tether to provide quarterly reserve reports for the next two years, which have been ongoing. Shortly after the NYAG settlement, in October 2021, the CFTC ordered Tether and Bitfinex to pay civil monetary fines totaling $42.5m over false claims that Tether was fully backed by US dollars.

After both the NYAG and the CFTC settlements, Tether was hit with a class-action lawsuit in December 2021, that similarly alleged the company had misrepresented its reserves, calling its practices “immoral, unethical, oppressive, and unscrupulous.” Tether quickly responded to the claim, calling it “another nonsense, copycat lawsuit” and a “shameless money grab.” Several of those claims have already been dismissed but litigation is still ongoing.

Today, Tether is still facing criticisms over the opaqueness of its reporting, including that its executives have yet to deliver a full audit after claiming in July 2021 that an audit was “months” away, though in early July 2022, CTO Paolo Ardoino stated in an interview that Tether had selected a “Big 12” auditing firm. The reported assets included in Tether’s attestation reports has been a prominent concern, particularly that as each asset class carries varying levels of liquidity and credit risk (e.g., individual line-items such as CP, secured loans, and “other investments”) that results in asset-liability mismatches and could impact redeemability. In addition, market participants have little visibility into Tether’s reserve assets in real-time, with end-of-period reporting for its quarterly attestations creating opportunities for Tether to hold riskier assets that can then be replaced with safer assets closer to the end of each quarter. Regardless of the validity of some of these criticisms, which we may never uncover, Tether claims it has been de-risking its reserve profile and that Tether has so far met every one of its redemption requests in a timely manner.

Tether Issuance and Redemptions

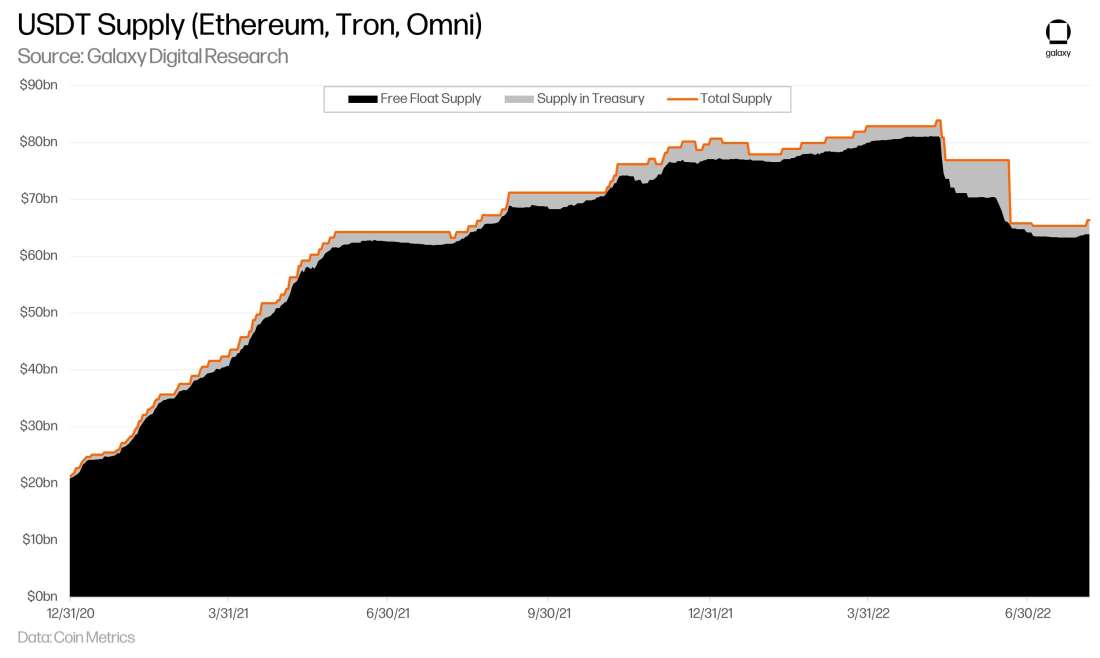

Minting of Tether tokens is available to Tether customers. Tether requires a minimum of at least $100,000 for new deposits and withdrawals in order to mint/redeem USDT, charging a fee of 0.1% on both transactions. Tether maintains a portion of USDT supply in treasury, split among several treasury wallets on each blockchain (e.g., its Ethereum wallet, Tron wallet). The USDT supply held in these wallets are considered “authorized but not issued,” meaning they are not counted in the market cap of USDT. USDT is only issued or released for circulation after Tether customers make their fiat deposits at Tether’s partner banks and the USDT is sent out from the treasury.

Tether typically mints USDT in $1bn increments and uses its Treasury balance to gradually draw down from to meet customer issuance requests in a timely manner (rather than minting new USDT to then transfer to customers on-demand). Tether CTO Paolo Ardoino has claimed its practice of managing “authorized but not issued” tokens in this manner is for security purposes—i.e., to reduce the number of times that Tether must access and utilize the sensitive cryptographic keys required to mint USDT. Tether manages its Treasury similarly for redemptions: as users send in redemption requests by sending USDT to the Treasury wallet, the USDT is taken out of circulation – though it technically isn’t “burned” until Tether sends the USDT to an inaccessible address, which Tether also does in large, periodic transactions (illustrated by decreases in “Circulating Supply” line shown in chart below).

Given Tether’s issuance and redemption fee of 0.1%, arbitrage opportunities are presented when Tether price deviates outside the range of $0.999 – $1.001. When the price falls below $0.999, traders can purchase tethers in the secondary market to be redeemed through Tether at nominal value for a profit. Conversely, if Tether is trading above $1.001, traders could go to Tether to mint new coins to then be sold in the market at a gain. However, Tether may trade outside of this range if there are no willing arbitrageurs or if traders have concerns that their redemptions cannot be met either in full or in a timely manner.

In addition, Tether makes no guarantees that redemption requests will be met promptly or in-full. This is explicitly expressed in Tether’s legal disclaimer: “Tether reserves the right to delay the redemption or withdrawal of Tether Tokens if such delay is necessitated by the illiquidity or unavailability or loss of any Reserves held by Tether to back the Tether Tokens, and Tether reserves the right to redeem Tether Tokens by in-kind redemptions of securities and other assets held in the Reserves.”

Tether Reserves

Since the NYAG’s 2019 ruling, Tether has provided more detailed line items for each of the components of its reserves on an end-of-period quarterly basis through its attestation reports, which have been certified by independent auditor MHA Cayman. MHA Cayman provides an “assurance,” not an audit, that Tether Limited’s policies and procedures as they related to the company’s preparation of the data reviewed by MHA Cayman were “appropriate,” rather than whether they were followed. MHA Cayman does not actually review underlying data to confirm or deny whether claims made by Tether regarding its reserves are materially accurate. Instead, MHA Cayman solely offers an assurance that Tether’s reporting is “correctly stated” from an accounting standpoint “based on the balances set out” by Tether. Essentially, MHA Cayman confirms that Tether’s production conforms to its own procedures for making such a production and that it is properly formatted for accounting standards. Lastly, in addition to these quarterly reports, Tether also provides less-detailed daily aggregate balances that shows current issued and authorized amounts.

Tether Limited is listed as the custodian for USDT. In the past, Tether has declined to reveal where the exact locations of where reserves are held, noting that it is a private company with no obligations to do share that information (though some of Tether’s reserves have been revealed to be held at several small Bahamas banks).

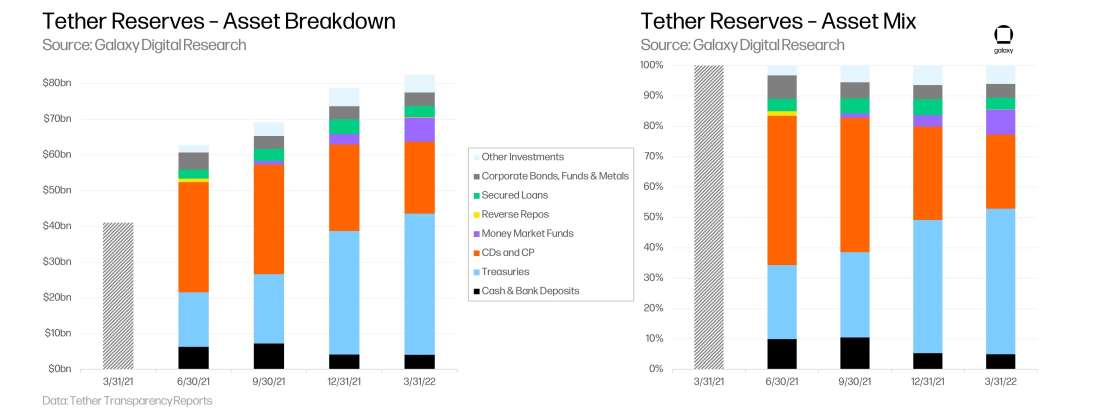

Over time, cash & cash equivalents and short-term deposits have formed a larger portion of Tether’s reserve composition. Cash & cash equivalents, other short-term deposits, and corporate paper stood at roughly ~85% of total reserve assets as of 3/31/22. For the 3/31/22 reserves report, Tether broke out the “Treasuries” line item to show the split between US and non-US Treasuries. Tether reduced its holding mix of CDs and CP—which some have alleged to be issued by risky Chinese entities—by more than half since 6/30/21 from 49% to 24% at 3/31/22.

In the 3 months since its latest reserves attestation report (3/31/22), Tether has stated that it has further reduced its CP holdings by nearly 50% to $8.4bn (including $5bn of which will expire on July 31) in its commitment to eventually taking its CP exposure down to zero. More recently, Tether confirmed that total CP exposure had been reduced to $3.7bn at July-end and that it expects the CP balance will go to zero by early November 2022. However, at the time of writing (August 8, 2022), Tether has yet to produce a Q2 2022 attestation report.

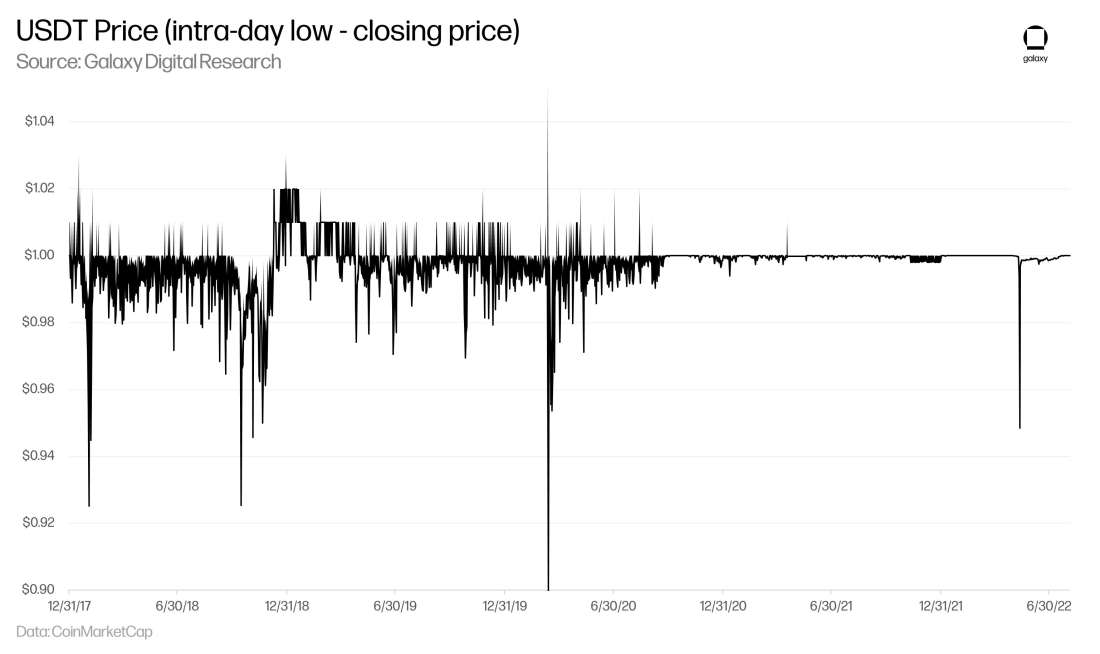

Since inception through late 2020, Tether has traded in a relatively wide range, frequently trading above or (more often) below its nominal value during intra-day trading. 2018 saw USDT trade below $0.98 on 39 days of the year. Price volatility of Tether has dramatically decreased since then, as 2019 and 2020 saw just 10 and 11 days, respectively, that Tether traded below $0.98 during intra-day, including on 3/13/20 when its price briefly fell below $0.90. This was followed by 0 days during 2021—in fact, Tether price didn’t fall below $0.995 on any of the days during the year.

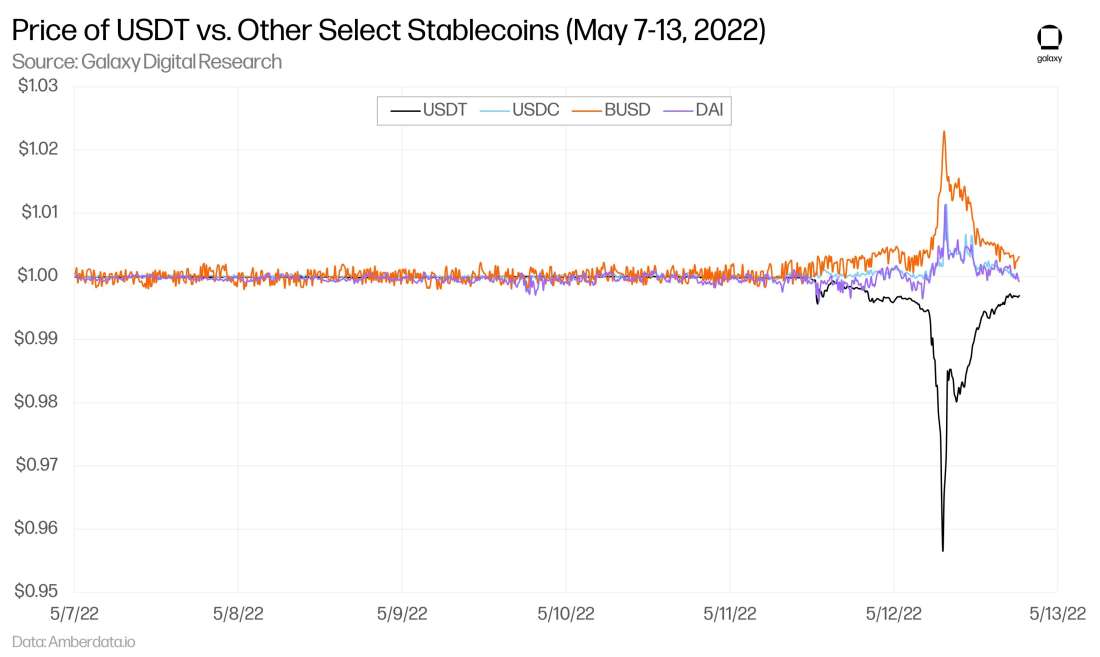

Tether’s price stability continued its improvement from 2021 through this year until the collapse of Terra USD (UST) reignited fears that Tether’s reserves were insufficient to cover its liabilities in a timely manner. Following the collapse of UST, USDT traded below $0.95 on 5/12/22. During Tether’s de-pegging to $0.95, the price of USDC saw the opposite reaction, rising to $1.05 across several exchanges, suggesting USDT holders exited their positions for the supposedly “safer” stablecoin. As it turns out, even though Tether has attempted to improve its risk profile in with greater reserve allocations to cash and short-term assets, its peg concerns have persisted, sparking back up after the market turns. In the short term, those fears appear to have eased as USDT has traded back above $0.999 since 5/13/22, though this slight $0.001 discount persisted on continued selling pressure for over two months before USDT finally fully recovered back to $1 by mid-July.

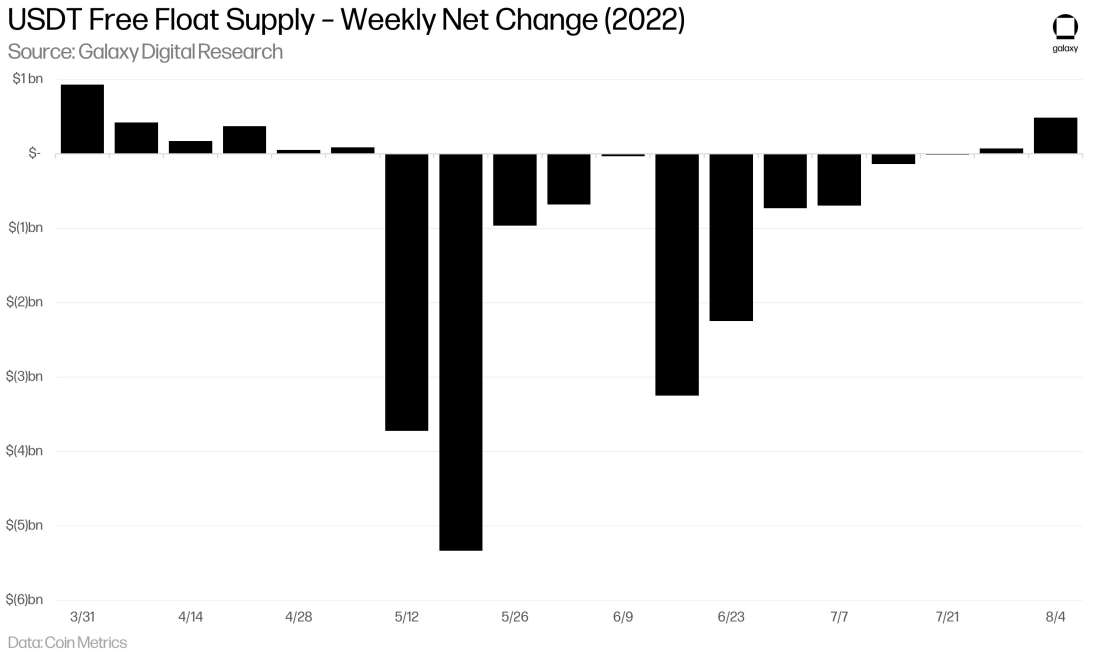

Tether also experienced a significant increase in redemption requests, partly driven by USDT holders looking to access the limited liquidity they believed to be held in Tether’s reserves, while other investors looked to take advantage of the arbitrage presented by the de-pegging – rarely seen since 2020. According to the flows in/out of its treasury addresses on Ethereum and Tron (and adjusting for mints/burns out of known addresses), Tether processed $12.5bn in redemptions requests during the month of May, including over $10bn over the 10-day period between 5/11/22 – 5/20/22 as the circulating supply of USDT dropped from $81bn to $71bn. This is estimated to have brought in at least $22m in revenue for Tether in May based on its 0.1% fee structure on issuance/redemptions.

USD Coin (USDC)

USDC (short for USD Coin), is the second most popular stablecoin today and was launched on Ethereum as a US-based alternative to Tether and other USD-pegged stablecoins in September 2018, just months after Tether stopped serving US customers. USDC is issued by Circle, but it was originally founded and developed by both Coinbase and Circle, which form the Centre consortium that governs USDC. The purpose of governing through this consortium was to strive for an industry standard using USDC as an example. USDC is issued through Circle but it also has local issuers that are regulated in the jurisdictions that they operate. Circle is a financial technology company that’s headquartered in Boston, Massachusetts and offers payments technology and treasury infrastructure to help bridge crypto with the traditional world. According to its website, “USDC is fully backed by cash and short-dated U.S. government obligations, so that it is always redeemable 1:1 for U.S. dollars.”

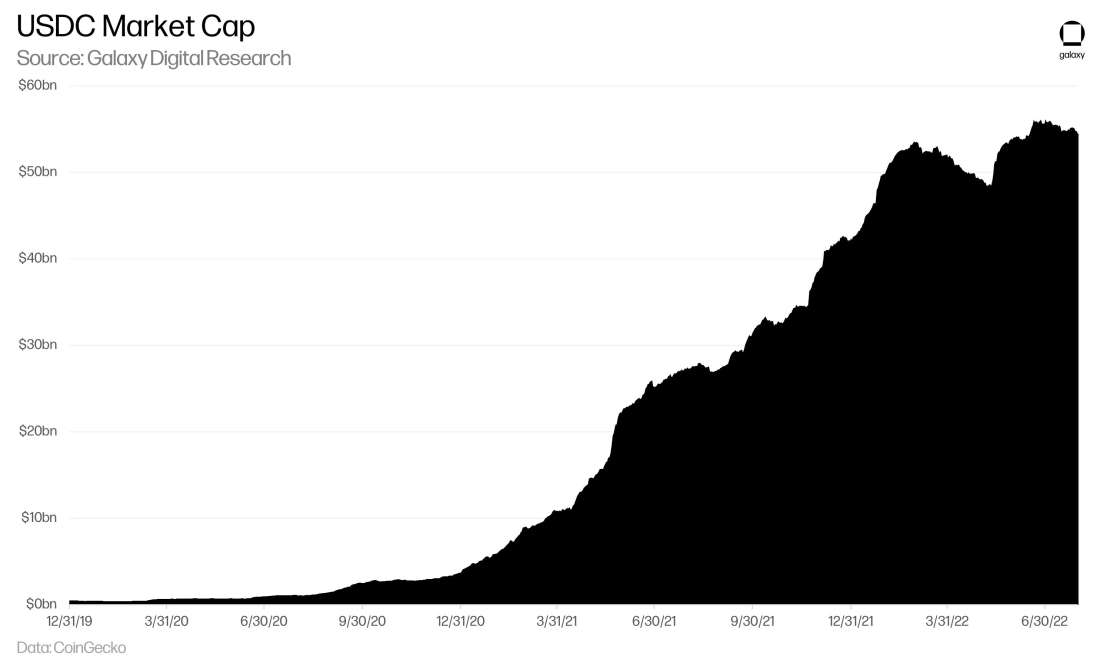

USDC’s adoption grew quickly as it has found footing as an on-ramp between fiat and crypto through relatively stable banking access for the US-based exchanges. Since its inception, USDC’s rapid growth has been eating into Tether’s leading share in the stablecoin market. As of 7/31/22, the circulating supply of USDC was ~55bn—approximately 83% of USDT supply. USDC has been integrated on 9 blockchains including Solana, Avalanche, Algorand, Stellar, and Flow.

Despite marketing its stablecoin as being relatively safer than Tether, Circle has also found itself in the crosshairs of US litigation. Circle received an investigative subpoena from the SEC in July 2021 that requested “documents and information regarding certain of our holdings, customer programs and operations.” The subpoena came just one month after Circle announced its fixed rate yield product for USDC, called Circle Yield, which was going to be offered by Coinbase to its customers. Before Coinbase customers could access the 4% USDC APY program, Coinbase pulled the launch of Coinbase Lend as it awaits more regulatory clarity. Circle Yield is currently offered through Circle Bermuda to accredited investors and is issued in the United States as a registration-exempt security pursuant to Reg D under the Securities Act of 1933 (not available in AK, MN, NY, HI).

In August 2021, CEO Jeremy Allaire shared that Circle intends to become a full-reserve national commercial bankthat will be regulated and supervised by the Fed, Treasury, OCC, and the FDIC. However, at the time of writing, Circle has yet to achieve registration with any of those banking regulators (the Treasury isn’t a banking regulator per-se, but Circle does comport to FinCEN AML/KYC requirements). Circle currently operates through state-based virtual currency and money transmitter licenses--though it notably lacks either a trust license or the elusive BitLicense from the New York Department of Financial Services (NYDFS). Competitor stablecoin issuers Paxos (behind Pax Dollar (USDP) and Binance USD (BUSD)) and Gemini (behind Gemini USD (GUSD)) both possess licenses from NYDFS.

USDC Issuance / Redemption

Minting and redemption of USDC requires one to open a Circle Account. Circle and its banking partners do not charge fees when minting USDC or redeeming USDC for dollars. Minting USDC requires users to send USD to the bank of a licensed CENTRE issuer, and the issuer then verifies the funds have been deposited and submits a request to USDC’s relevant token contract to mint an equivalent amount of USDC which is then deposited to the user’s wallet.

Redemption of USDC follows a similar process in reverse – the user submits a request for redemption from a USDC issuer, which sends the USDC to the smart contract to be burned or taken out of circulation, and then the equivalent amount fiat funds from the USDC reserves are transferred to the customer’s bank account upon successful verification and validation.

Unlike the minimum requirements to create and redeem USDT, there is no minimum tokenization amount when minting USDC, but redemption of USDC for dollars has a minimum requirement of $100. Minting occurs within minutes after deposits have settled in Circle’s account (though this is still subject to slow bank transfers which may take 2 business days to process). The mint and redeem functions for USDC are available to users 24/7 (also subject to bank hours and delays). Circle has banking partners that may enable faster settlements including Silvergate, which is working on enabling real-time settlements available 24/7 for its banking customers.

USDC Reserves

USDC reserves are held in segregated accounts that cannot be used by Circle and are protected in the event of a Circle bankruptcy. USDC has reserve attestation reports published monthly by Grant Thornton LLP which date back to October 2018. Most of these attestation reports confirm that the total fair value of assets held on behalf of USDC holders is at least equal to the total USDC in circulation on approved blockchains (less tokens allowed but not issued and blacklisted tokens).

Starting May 2021, the attestation reports provided more detail behind the breakdown of USDC reserves. On May 31, 2021, USDC had 61% in cash & cash equivalents, with the remainder split among Yankee CDs, US Treasuries, Commercial Paper, Corporate Bonds, and Municipal Bonds & US Agencies. But following an update in August 2021, reserves held in Yankee CDs and Treasuries contradicted Coinbase’s assertion on its website that “each USDC is backed by one US dollar held in a bank account,” which resulted in Coinbase modifying its description of USDC to say USDC is “backed by fully reserved assets.” Over time, the reserves for USDC have slowly transitioned to be 100% backed by just cash & cash equivalents, achieving this by 9/30/21.

On July 5, 2022, Circle released a statement saying 80% of USDC reserves were in US T-bills with durations of 3 months or less – all purchased by BlackRock and custodied at BNY Mellon. The remaining 20% was in cash held at banking partners including Silvergate, Signature Bank, and New York Community Banks—these balances are meant to meet redemptions of USDC upon request, to be available outside of normal banking business hours, 24/7/365.

Circle vs. Tether

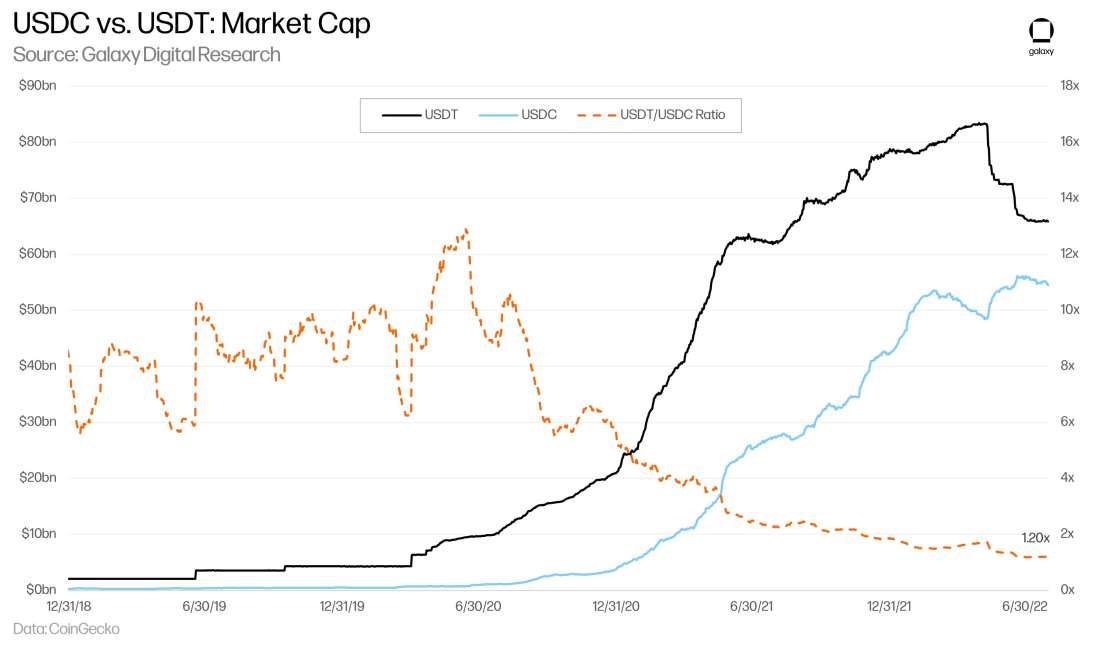

USDT’s lead against USDC in terms of market cap (across all networks) reached a recent peak of more than 12x in May 2020, but has since fallen at a rapid pace. As of July 31, 2022, the market cap of USDT stood at $65.9.5bn compared to $54.5bn for USDC, representing a USDT/USDC ratio of just 1.20x—the lowest ratio in the stablecoins’ history.

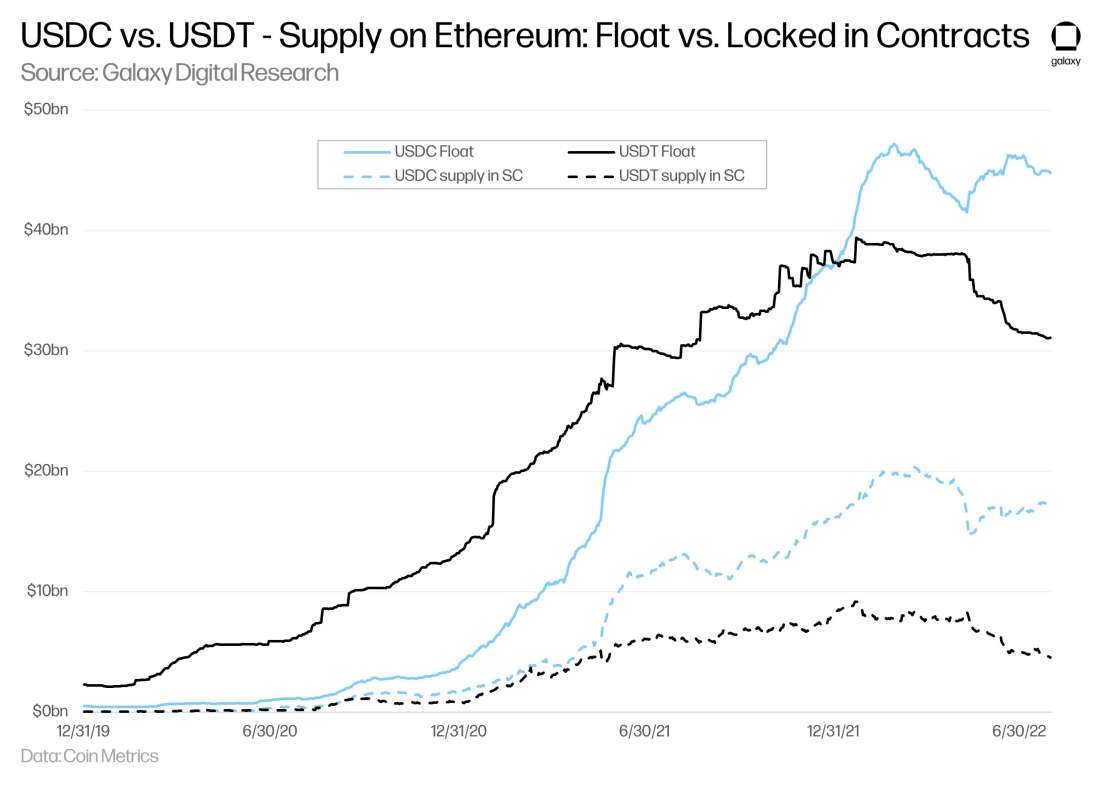

At the start of 2022, USDC’s free float supply on Ethereum surpassed that of USDT, and it has since continued to widen the gap; as of 7/31, USDC supply totaled $45bn – 44% more than the $31bn in USDT on Ethereum.

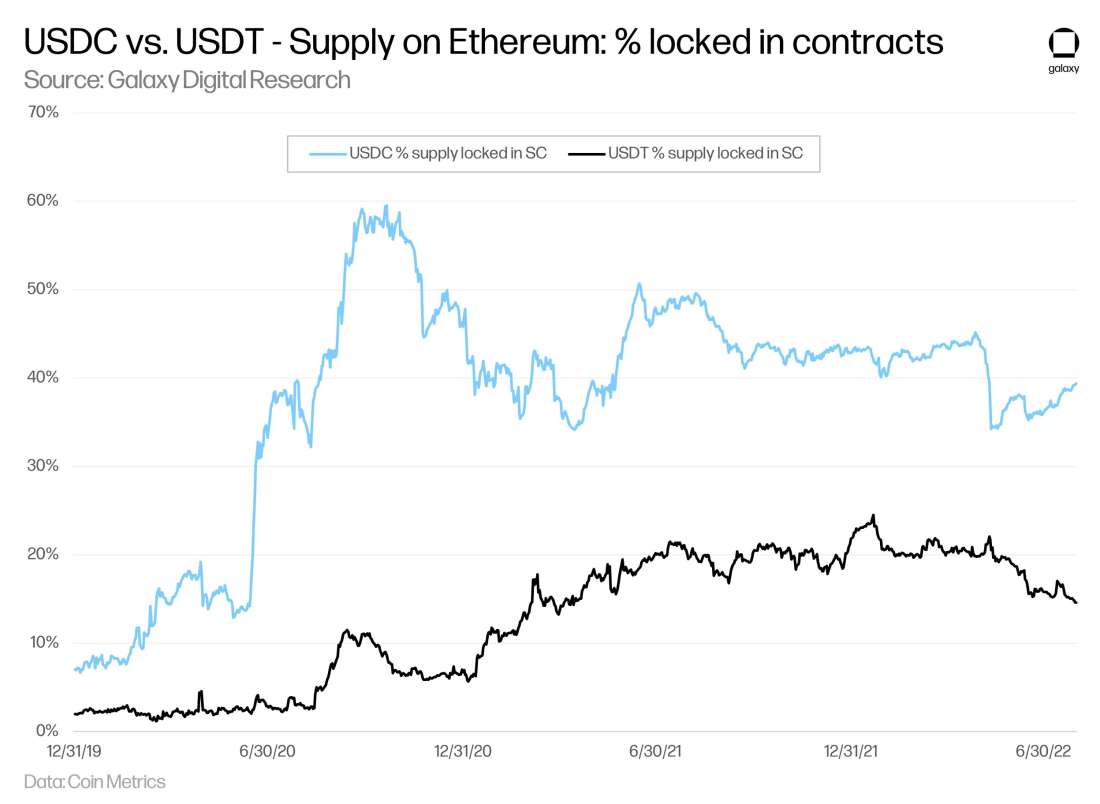

USDC typically has a greater % of its supply on Ethereum locked-in smart contracts compared to Tether – YTD, USDC has averaged more than 2.1x the level of USDT on this metric. This would align with the presumption that Tether is mostly used as an on- and off-ramp for trading at exchanges (due to banking restrictions in China), whereas in the US, most users can on-ramp using dollars from their bank accounts rather than having to rely upon stablecoins, enabling more of its supply to be used outside of exchanges.

Fiat-backed Stablecoin Landscape

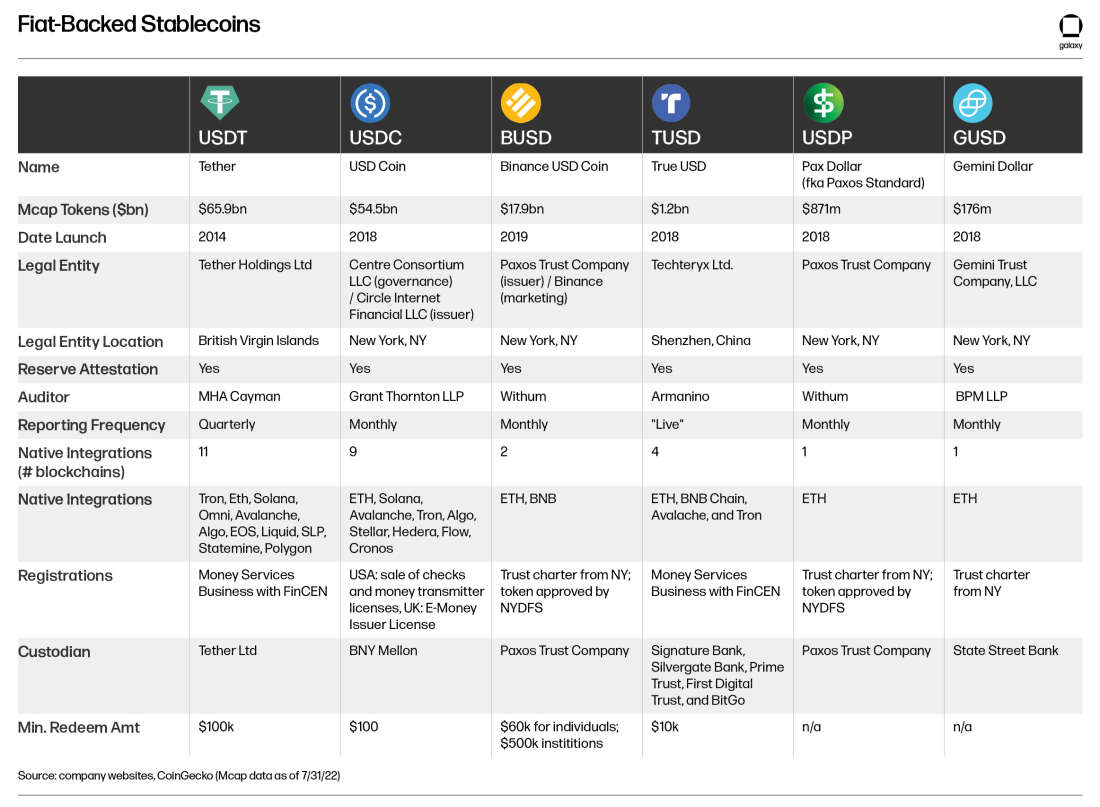

Binance USD (BUSD) is the 3rd largest fiat-backed stablecoin at $18bn, only one-third of the circulating supply of USDC and one-fourth of the circulating supply of USDT. BUSD was created in partnership between Binance and Paxos, which is a trust company and custodian regulated by the NYDFS (Paxos also issues Pax Dollar (USDP) and PAX Gold (PAXG)). During the initial discussions with the NYDFS, Paxos had agreed that USDP and BUSD would only be issued on the Ethereum blockchain (BUSD token on BNB Chain is issued by Binance as Binance-Peg BUSD).

Paxos first provided a breakdown of its reserves for BUSD and USDP for the period ended 6/30/21, which came shortly after Tether first disclosed a breakdown of its reserves following the settlement with the NYAG. Relative to Tether and Circle, Paxos showed a safer and more liquid reserve composition with 96% held in cash & cash equivalents and the remainder held in US T-bills. More recently, for the period ended 6/30/22, Paxos committed to providing an greater level of transparency beyond what its regulators require by providing the CUSIP of all securities backing USDP and BUSD – a practice that it intends to follow on a monthly basis moving forward. Circle has since followed suit starting with the period ended 6/30/22.

True USD (TUSD) is issued by Techteryx and is based in Shenzen, China. TUSD relies on Chainlink and Armanino’s TrustExplorer solution to provide real-time assurances for both on-chain and off-chain balances, including those that are held in TrueUSD’s escrow bank accounts. With Armanino sending real-time audited data to Chainlink, TUSD introduces Proof of Reserve & Supply reference contracts that provide increased transparency compared to other fiat-backed stablecoins that rely upon monthly attestation reports. The issuer is partnered with banks including Signature Bank, Silvergate, Prime Trust, First Digital Trust, and BitGo.

Other fiat-backed stablecoins include stablecoins issued by centralized exchange entities (Huobi-branded HUSD issued by Stable Universal / Gemini Dollar (GUSD) issued by Gemini). HUSD asserts it is backed 100% by cash held in money market accounts and does not contain “cash equivalents” such as US T-bills, bank CDs, or other money market funds. GUSD reserves are held in accounts at FDIC-insured banks or money market funds holding short-term US T-bonds. Gemini is the only stablecoin issuer other than Paxos to be regulated by the NYDFS.

Competitive dynamics

All stablecoins mentioned thus far in this report are currently issued by for-profit private businesses. Each seeks to drive adoption of their stablecoin, though they may prioritize different uses of the stablecoin which impact their competitive dynamics. Fiat-backed stablecoin issuers also look to drive adoption of their stablecoin through different use cases including banking integrations for on-and off-ramps, payments, usage on trading venues, availability in DeFi platforms, etc.

Fiat-backed stablecoins compete on trust and regulation (most stablecoin users never interact with the issuance/redemption processes). That means that they typically market themselves based on the quality of their reserves (many committed to 100% cash & cash equivalent backings) along with frequent reserve attestations. Having third-party confirmations from trusted partners also goes a long way in establishing trust for stablecoin issuers. The direct customers of stablecoin issuers are often segmented by geography, with on-shore issuers (e.g. Circle, Paxos, Gemini) servicing US customers and off-shore issuers (e.g. Tether) finding more adoption with global customers, including most based in Asia.

The primary competitive factors that fiat-backed stablecoin issuers compete on:

Reserve composition and transparency. Token holders of stablecoins are taking on counterparty risk through the issuers so to properly assess that risk, they require auditability or sufficient details on the types and amount of assets held in reserves. Safer reserve profiles, strong collateral management practices, more frequent updates, and greater detail of reporting will likely win over customers that prioritize safety over ancillary product offerings such as yield.

Distribution architecture. Stablecoin issuers work closely with bank partners, custodians, and exchanges for distribution. The licenses obtained by the issuers impacts the jurisdictions that they operate and who they can do business with. These licenses often have restrictions on the composition of reserves and the types of assets permitted to be held in backed reserves.

Other product offerings. They may offer customers ancillary products and offerings that may influence the adoption and utility of their stablecoin including banking integrations, payment services, yield, blockchain integrations, etc.

Fiat-backed Stablecoin Issuers – Interest Income

Fiat-backed stablecoin issuers have a similar business model to traditional commercial banks, where the primary source of revenue comes from net interest—the difference between interest income earned on deposits less interest expenses—making deposit growth the core objective. In their current form, however, no fiat-backed stablecoin issuers pays any interest to depositors, enabling them to generate significantly higher margins than traditional banks. Rising interest rates also benefit the issuers substantially. For a stablecoin with $1bn in deposits, each 25 bps increase results in $2.5m in incremental interest income.

The income generating potential on deposits varies significantly depending on the composition of reserves and the portfolio duration, which is largely dictated by competition with other stablecoin issuers and proactive compliance with expected upcoming regulatory guidance. Between the different stablecoin issuers, the balance between assets and cash requirement will be the primary determinant of the differences in revenue potential. Paxos + Gemini (BUSD, USDP, GUSD) generally have the most conservative reserve composition, as they are overseen by the relatively stringent NYDFS, while Circle (USDC) has slightly more operating flexibility. On June 30, 2022, T-bills represented 60% of BUSD’s reserves and had an average duration of 42 days vs. 76% for USDC at an average duration of 58 days (our duration estimates). These differences in duration and portfolio mix can have a meaningful impact on interest income.

Using this framework, we can make some assumptions about issuer revenue. If we conservatively assume that returns on cash deposits are negligible and that Circle is earning roughly the current 8-week T-bill coupon equivalent rate of 2.36% based on its token duration, then Circle would generate ~$1bn in annual interest income. However, if USDC had a reserve composition that had the duration and asset mix of Paxos, then Circle would only earn ~$725m in annual interest income, ~$275m (or 27.5%) less (holding portfolio size constant and assuming negligible returns on cash and reverse repos, as well as a ~20 bps difference in coupon equivalent rates based on token durations). If expected future regulation for stablecoin issuers requires each to follow similar reserve practices, then the gap in interest income potential would narrow significantly (more on regulatory discussion on p. xx).

Financial Analysis of Fiat-backed Stablecoins

Peg Stability

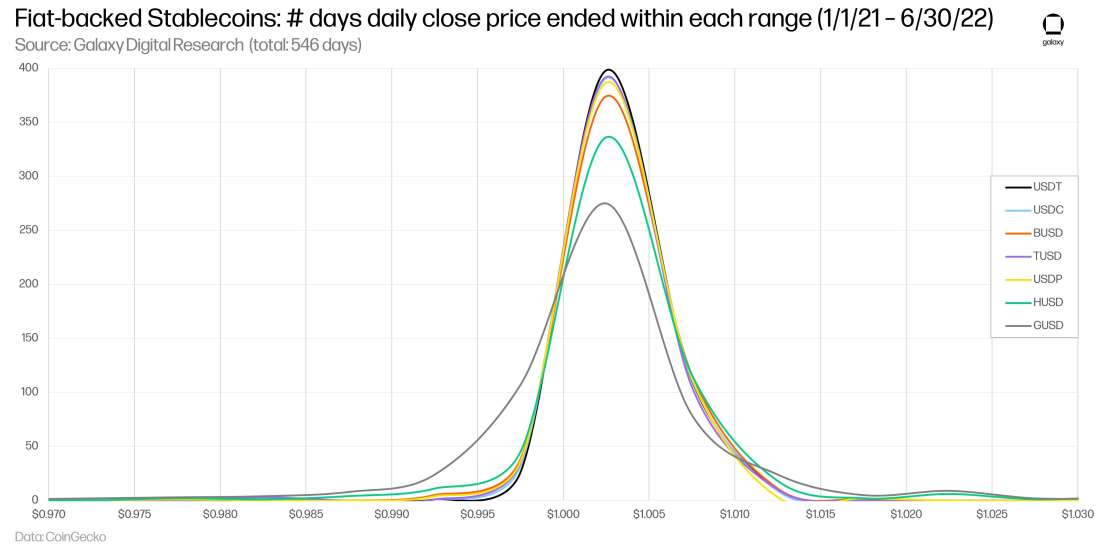

Based on the daily closing price (UTC), USDT has had the highest count of daily closing prices between $0.9975–$1.0025 of our sample of fiat-backed stablecoins with 398 days (7 more days than USDC) since January 1, 2021. USDT daily closing prices also had the lowest standard deviation compared to its competitors ($0.0024 vs $0.0027 for USDC).

When looking at the daily low prices across the same sample and time range, USDT’s daily low trading level averaged $0.9994 – the closest to $1 out of its group. However, USDT also saw 3 days where its price traded below $0.995 including 1 day where its price fell below $0.95 (May 12, 2022). Only Gemini Dollar had traded below that level in this sample. By frequency of days, BUSD had performed the best with 0 days that its price traded below $0.995, followed by USDC with just 1 day below that level.

USDT had the most frequent number of days that its trading price stayed near $1 (based on daily low prices), but in terms of downside protection, BUSD has been the best performing fiat-backed stablecoin, followed closely by USDC.

Usage

Note: the data shown in this section is for transfers on Ethereum only. It does not include USDT usage on Tron or BUSD usage on BNB Chain (both of which have higher activity levels than they do on Ethereum).

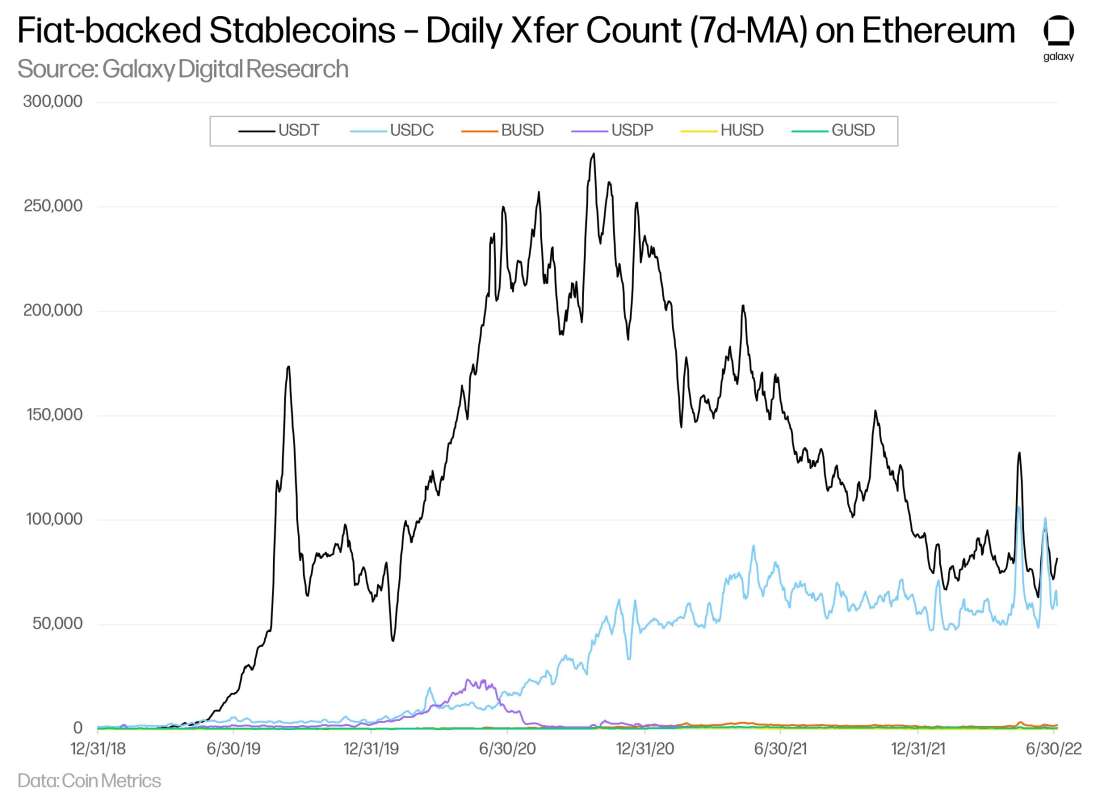

USDT and USDC have averaged over 60k transfers daily during 1H22, both considerably higher than their fiat-backed counterparts. Like their market cap dynamics, USDT’s once-commanding lead over USDC has diminished considerably over time.

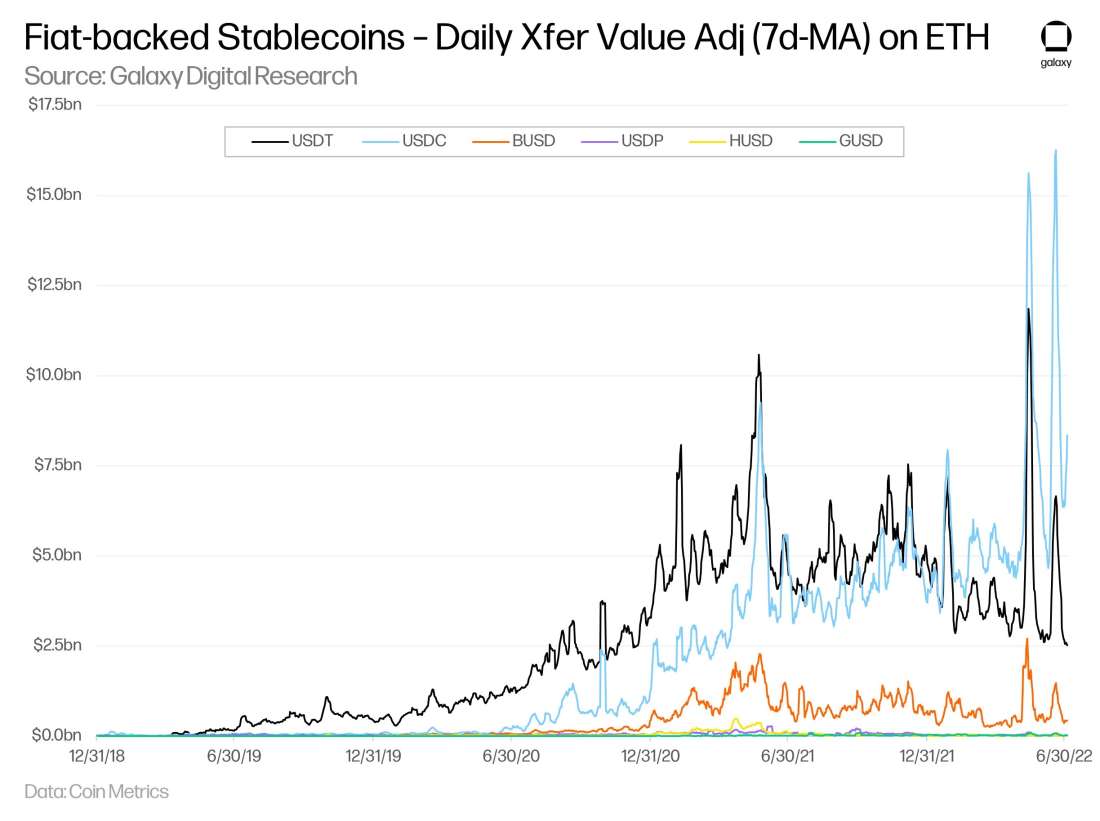

USDC’s total transfer value on Ethereum has surpassed USDT’s so far over 1H22, totaling $1.14T compared to $746bn for USDT. The next closest in total transfer volume on Ethereum is BUSD with $123bn, ~12% of the volume of USDC despite it having roughly 2% of the transaction count.

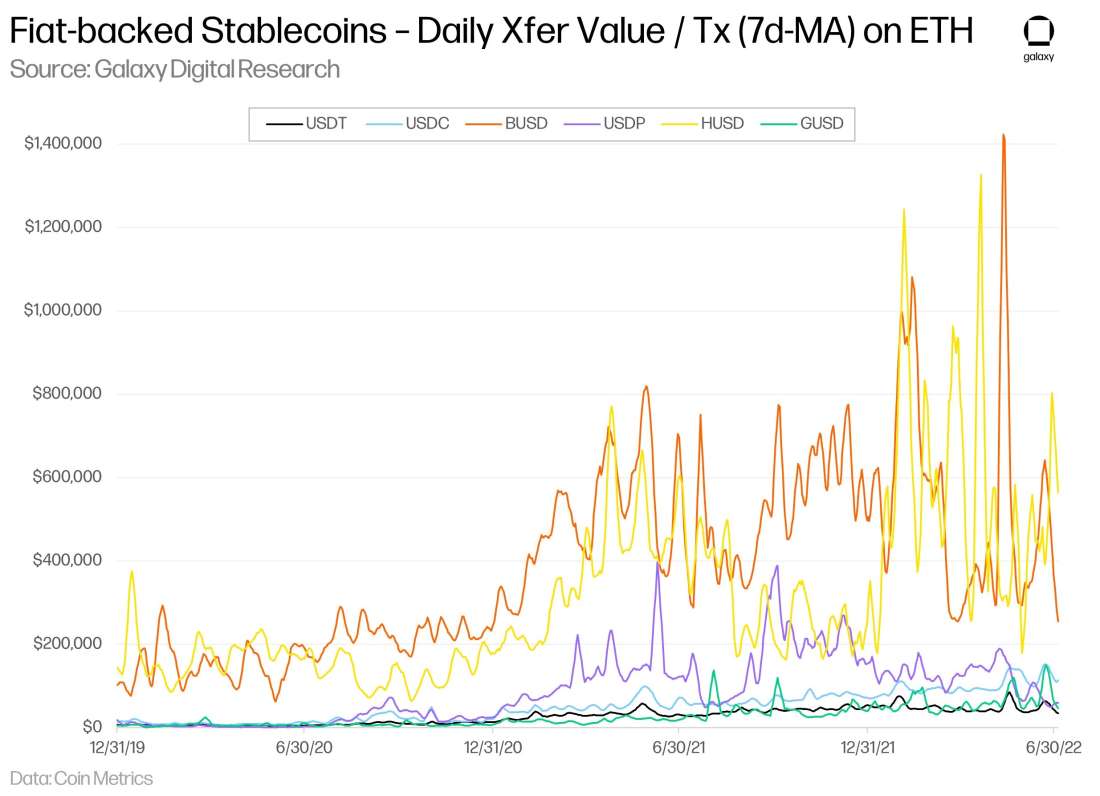

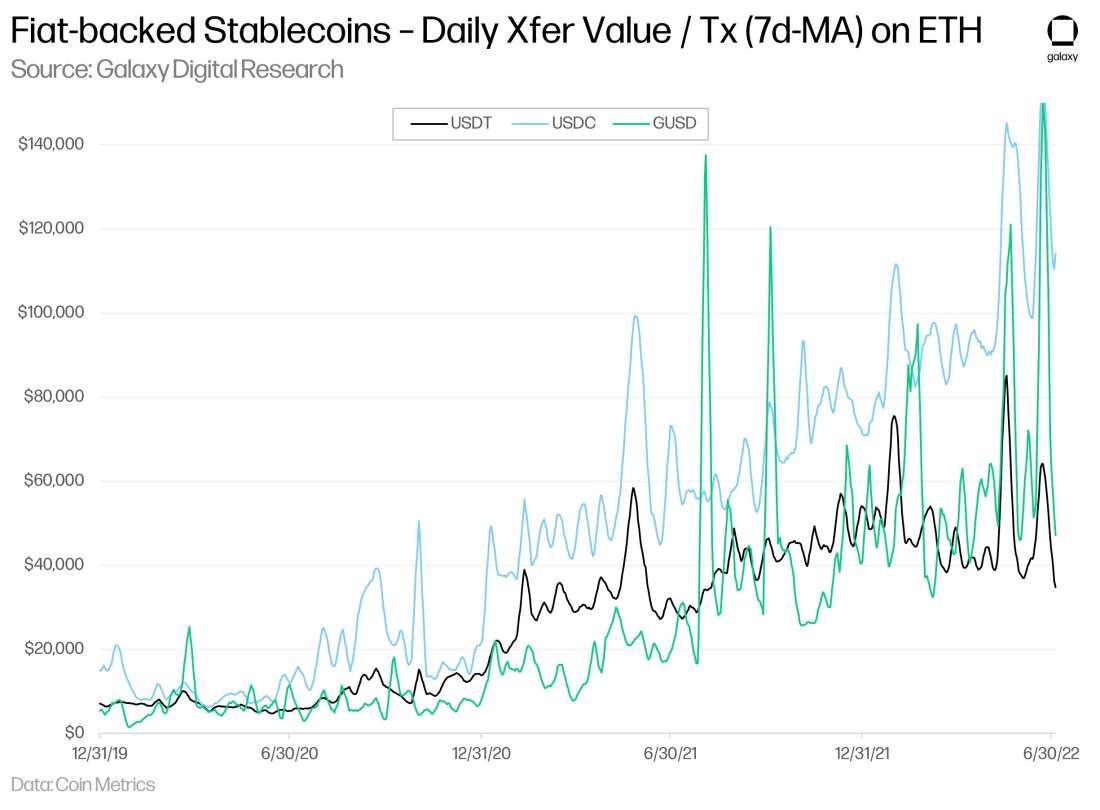

BUSD and HUSD transfers on Ethereum have the highest value of the group, averaging over $500k per transaction during 1H22. This compares to $106k for USDC and $50k for USDT. In terms of median transfer value, HUSD leads at $250k whereas the median transaction size of BUSD is closer to $1k – in-line with the median of USDT and USDC. This reflects HUSD’s usage primarily in inter-exchange settlements and B2B applications, whereas the other fiat-backed stablecoins have a larger mix of retail usage, especially for DeFi activity.

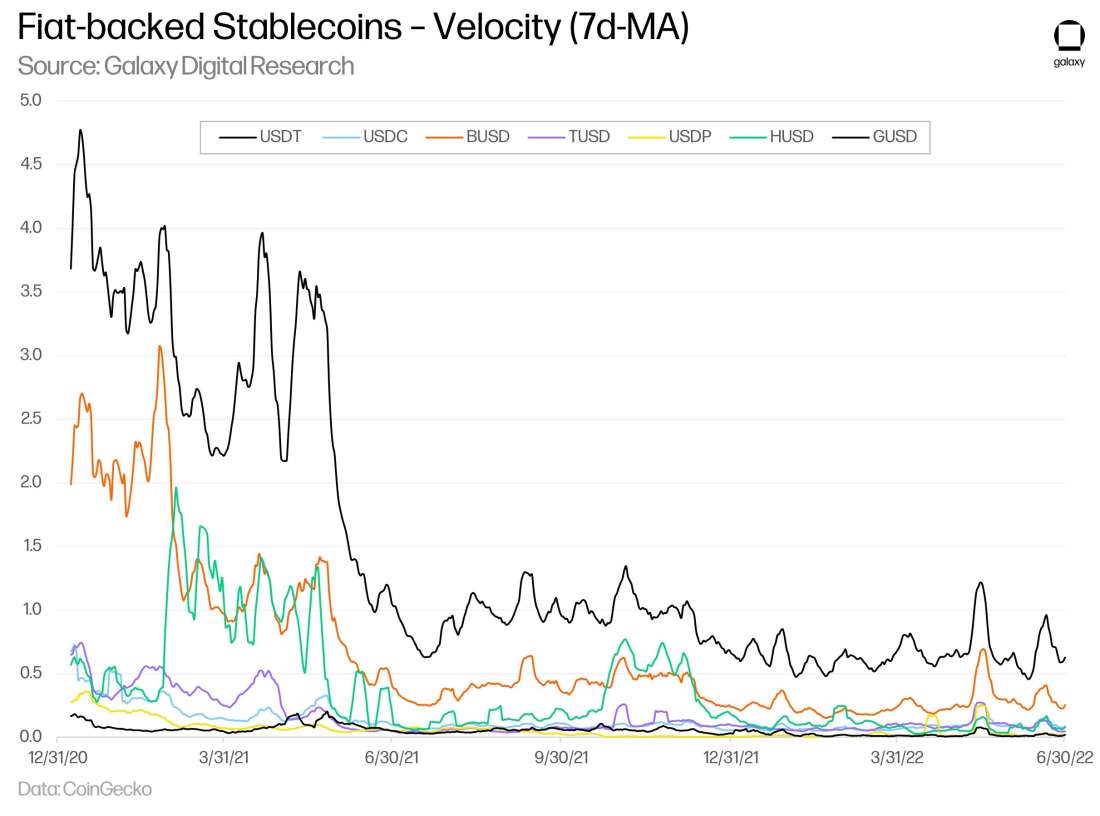

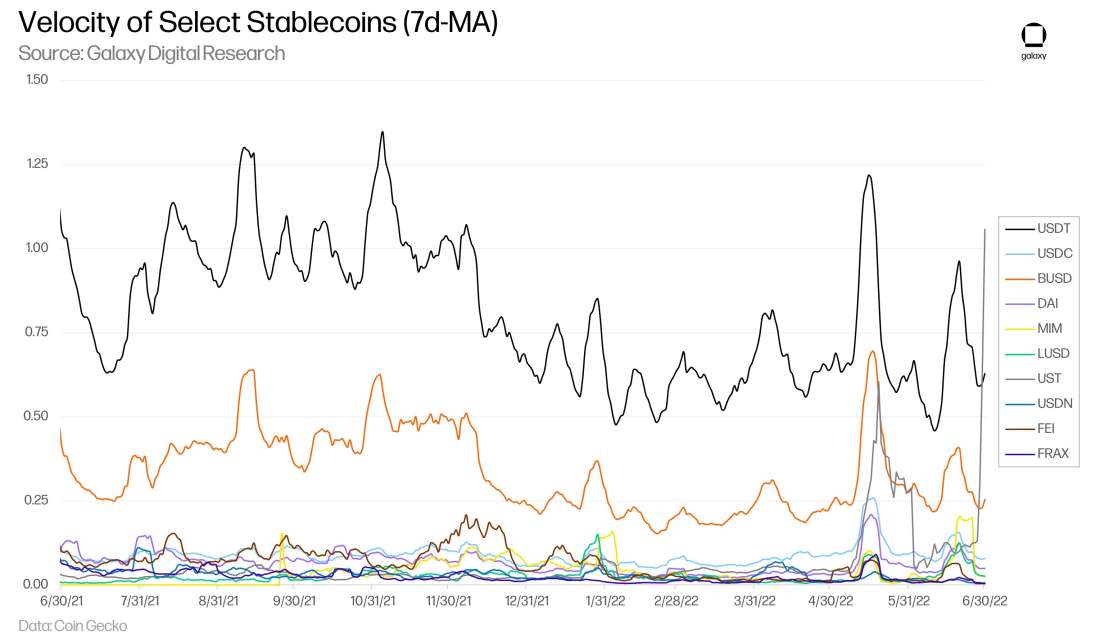

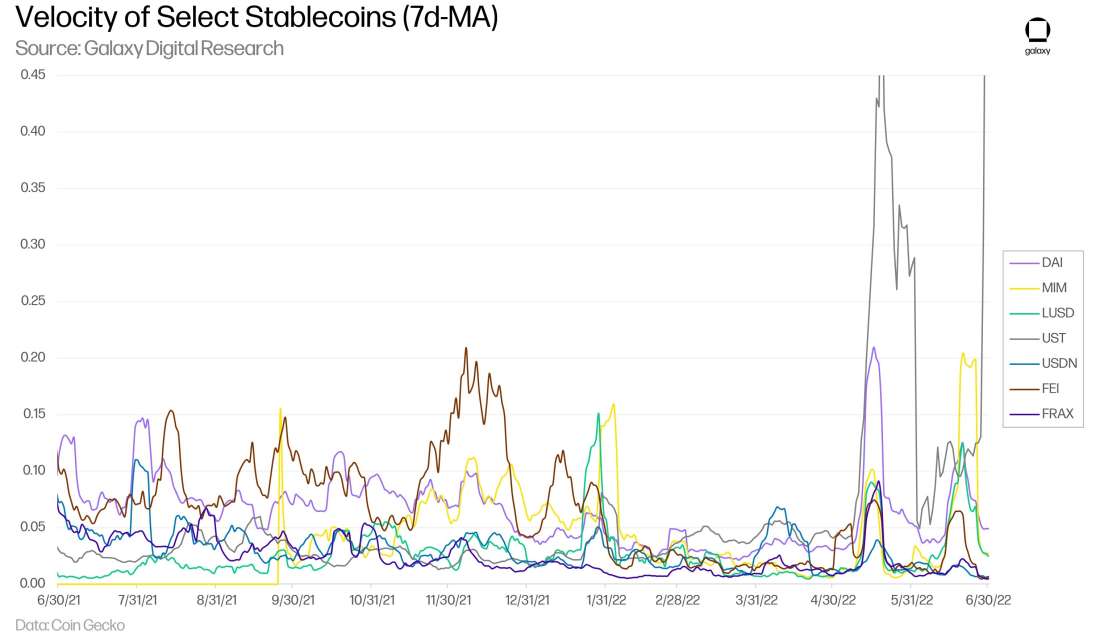

Velocity: The velocity of money measures the rate at which money is transacted over a given period of time. We calculate velocity as the 7-day moving average of daily trading volume / supply.

USDT has the highest velocity of the group by a large amount, though its velocity has decreased considerably since May 2021 after China initiated its ban on crypto. For 1H22, the velocity of USDT averaged 0.66—2.5x more than the next closest stablecoin (BUSD @ 0.26). USDC velocity YTD has averaged 0.09 – approximately 1/8th the velocity of USDT, suggesting USDC is used much less as a base currency for active trading.

Primary Risks of Fiat-backed Stablecoins

The primary risks associated with fiat-backed stablecoins include run-risk or redeemability of the stablecoin—primarily a function of the composition of reserves—and regulatory uncertainty as a comprehensive regulatory framework has yet to be enacted, which may significantly impact the operations of existing stablecoin issuers. With regards to the rest of the crypto economy, fiat-backed stablecoins are criticized for being custodial (reserves are custodied by the issuer or a trust) and centralization risk (single point of failure, ability to make decisions unilaterally). In addition, due to the lack of transparency around reserve holdings, the demand for specific fiat-backed stablecoins may be influenced by speculation around the quality of collateral (includes credit risk, liquidity risk, rate risk, etc.).

Freezing funds

Fiat-backed stablecoin issuers are subject to compliance with legal obligations regarding KYC/AML and transaction monitoring activities. To remain compliant with these laws, fiat-backed stablecoin issuers may maintain the administrative ability to “freeze” their stablecoins—or prevent a particular address from interacting with their stablecoin—by maintaining a blacklist of these blocked addresses.

For USDT and USDC, the blacklists are managed by Tether and the Centre consortium (not the individual issuing members), but addresses are typically added at the request of law enforcement. When a transfer function on USDT or USDC is called, the token smart contract queries an off-chain blacklist to ensure that neither the sending nor receiving address is present. If the address appears on the blacklist, the transaction is blocked. While this authority may not grant the ability to blacklist individual tokens or to seize the tokens from a particular address, it enables the ability to essentially render the tokens useless for blacklisted addresses. This capability is certainly useful for several occasions as we have seen following the Poly Network $611m exploit in August 2021 when Tether froze $33m in USDT on Ethereum before the exploiter was able to transfer the stolen funds. It serves AML and CFT purposes well by restricting sanctioned addresses from redeeming to fiat where illicit funds may be more difficult to trace. In addition, it also may also comfort users knowing that there may be a recovery mechanism in place if sending tokens to the wrong address – once transactions are finalized on-chain, they are typically irreversible, but Tether can recover the funds by freezing the wrongly-sent USDT to then be re-issued to the original sender in certain cases.

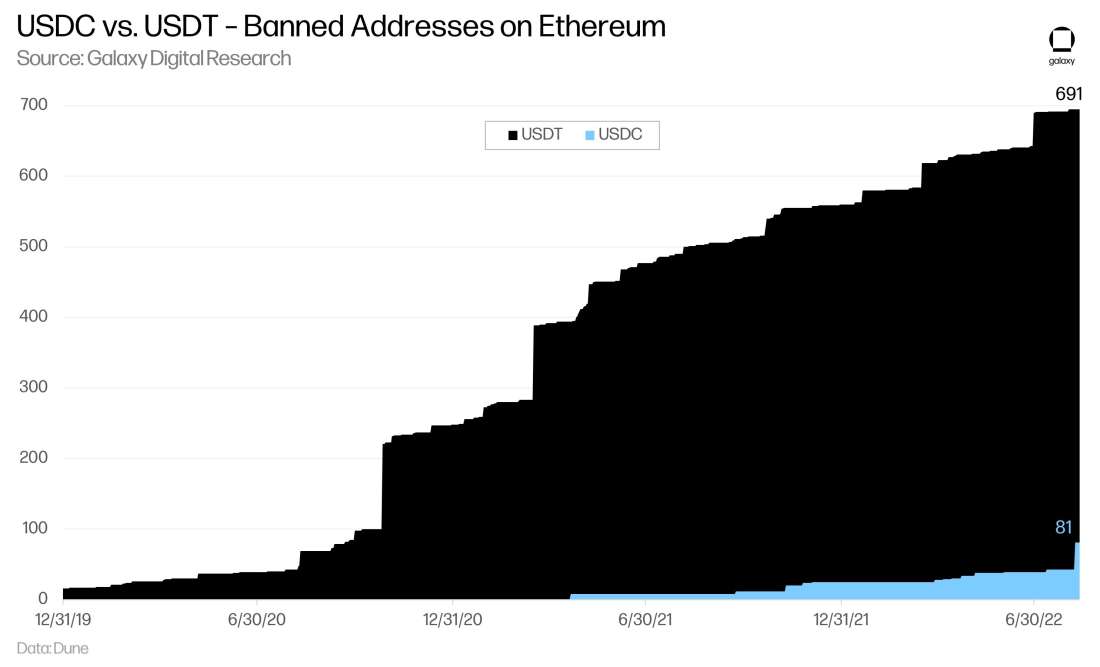

As of 7/31/22, Tether has blacklisted a total of 691 addresses on Ethereum – 50 of which were added since 6/30 (does not include banned addresses on other networks). Collectively, there is over $400m USDT frozen, averaging ~$580k/wallet and equating to 0.6% of circulating supply. Compared to USDT, there are significantly fewer blacklisted USDC addresses on Ethereum, totaling just 43 as of 7/31/22. “Access denied tokens” totaled 4.0m USDC, averaging ~90k/address per address and equating to 0.007% of total USDC supply. [8/9/22 update: Following Treasury mandated sanctions against Tornado Cash, the Centre consortium blacklisted the 38 related addresses (collectively holding $149k), bringing its total up to 81. Although complying with the Treasury’s orders, Circle shared in a blog post that it disagreed with the unprecedented sanctioning against an open-source protocol and would be challenging the logic of the order. For further details, read more about the Tornado Cash update in our research note.]

Following UST’s collapse in May, Circle communicated that all of the unique assets blocked to date have been at the direction of law enforcement to comply with OFAC sanctions and court orders, adding that “blocking is never done unilaterally or arbitrarily and follows the highest duty of care.” However, this statement is somewhat misleading (perhaps implying Circle doesn’t have the unilateral or arbitrary ability, but the Centre consortium does) as addresses can also be blacklisted for protection of user funds or for suspicion that the stablecoin may be associated with illegal activity. In these instances, Tether and Centre technically do have sole discretion to block transactions by certain addresses outside of what law enforcement requires. Per Centre’s blacklisting policy, the consortium reserves the ability to add addresses to the blacklist “where Centre determines, in its sole discretion, that failure to grant a blacklisting request presents a threat to the security, integrity, or reliability of the USDC Network, including security breaches that compromise USDC privileged keys (e.g., minter private key) and result in unauthorized USDC being minted from such compromise.”

Still, this authority to block transactions reflects some of the limitations of fiat-backed stablecoins especially for on-chain activity like in DeFi applications. Users have little visibility into the decision-making that goes into blacklisting addresses, which contrasts with the (ideally) open, transparent governance processes in crypto networks that puts decision-making in the hands of the community. Fiat-backed token holders must trust that the centralized stablecoin issuers are acting virtuously. It’s easy to see how having this blacklisting authority can be easily abused, especially in authoritarian regimes where crypto users stand to benefit the most. While the crypto networks and protocols may be permissionless to interact with, in the case of centralized fiat-backed stablecoins, the underlying assets used may not be. Indeed, this technology could also be used in the reverse—to restrict the transferability of fiat-backed stablecoins to any address that is not whitelisted. Were such a restriction to be imposed, it is likely that the majority of stablecoin activity would flow to more decentralized (and less regulated) stablecoin alternatives.

Overcollateralized Stablecoins

While fiat-backed stablecoins are collateralized by off-chain assets, overcollateralized stablecoins typically exist solely on-chain and are explicitly backed by crypto assets. Being entirely on-chain enables anyone to verify the composition of reserves backing the stablecoin, a level of transparency that no fiat-backed stablecoin issuer can offer. Overcollateralized stablecoins are powered by smart contracts and offer a more decentralized alternative to fiat-backed stablecoins, accepting deposits in crypto assets rather than dollars, and they require collateral deposits in excess of $1 to serve as a buffer against price volatility in the underlying collateral. Given the nature of these types of systems, demand for overcollateralized stablecoins typically comes from demand for leverage as opposed to on- and off-ramps like for fiat-backed stablecoins.

Stability mechanism of Overcollateralized Stablecoins

Issuance of overcollateralized stablecoins require users to deposit crypto assets (e.g., ETH) into a smart contract to serve as collateral against borrowed assets, which are typically in the form of stablecoins. The borrowed stablecoin is removed from circulation through user repayment, enabling depositors to retrieve their underlying collateral. The rates that borrowers pay and suppliers are paid can be set by variable interest rate models based on the amount of liquidity in the protocol and the utilization of each asset pool.

Like traditional bank balance sheets, users’ deposited assets represent assets for lending protocols, while borrowed assets represent liabilities. Compared to fiat-backed stablecoins, where assets (user fiat-deposits that are typically in the form of cash & cash equivalents or Treasuries) are matched 1:1 with liabilities (issued stablecoins), overcollateralized stablecoins require a higher balance of assets than liabilities to provide a safety buffer to help the protocol maintain solvency.

In addition, when assessing the aggregate positions of lending protocols from the top down, it may appear that the entirety of user deposits is used to back the total liabilities, but in most of these systems individual loans are backed by their own collateral positions, meaning the protocol cannot use excess deposits from one user to collateralize certain positions of other users that may failed.

The amount that can be borrowed is set by the Loan to Value Ratio (LTV) or sometimes called the Collateral Ratio (CR), which is the inverse of LTV. Protocols with higher risk tolerance allow higher LTVs upwards of 90%—typically reserved for the safest collateral assets—while more conservate protocols may apply lower LTV of 50-80%. If the LTV falls below its permitted range, then no new borrowings may be taken out, or collateral may be automatically liquidated to cover any imbalance. These parameters, as well as the types of collateral that can be accepted, can be adjusted from time to time via protocol governance, which takes various forms.

Overcollateralized stablecoins also rely on liquidations to ensure the protocol remains fully collateralized. If the value of a depositor’s collateral falls below the protocol’s LTV threshold or collateralization ratio minimum, then the borrower’s position may be liquidated—a process often automated by liquidation bots that involves selling the borrower’s collateral deposit to pay off the outstanding debt owed. Many protocols even offer their own off-the-shelf bots to make it easier for users to initiate the liquidation process. Liquidators may be incentivized through a liquidation fee that enables them to purchase the collateral at a discount. Ideally the LTV or CR plus the liquidation fee would be large enough to encourage liquidations to properly function by covering all outstanding debt in a timely manner, though this may not always be the case as protocols can also accumulate bad debt.

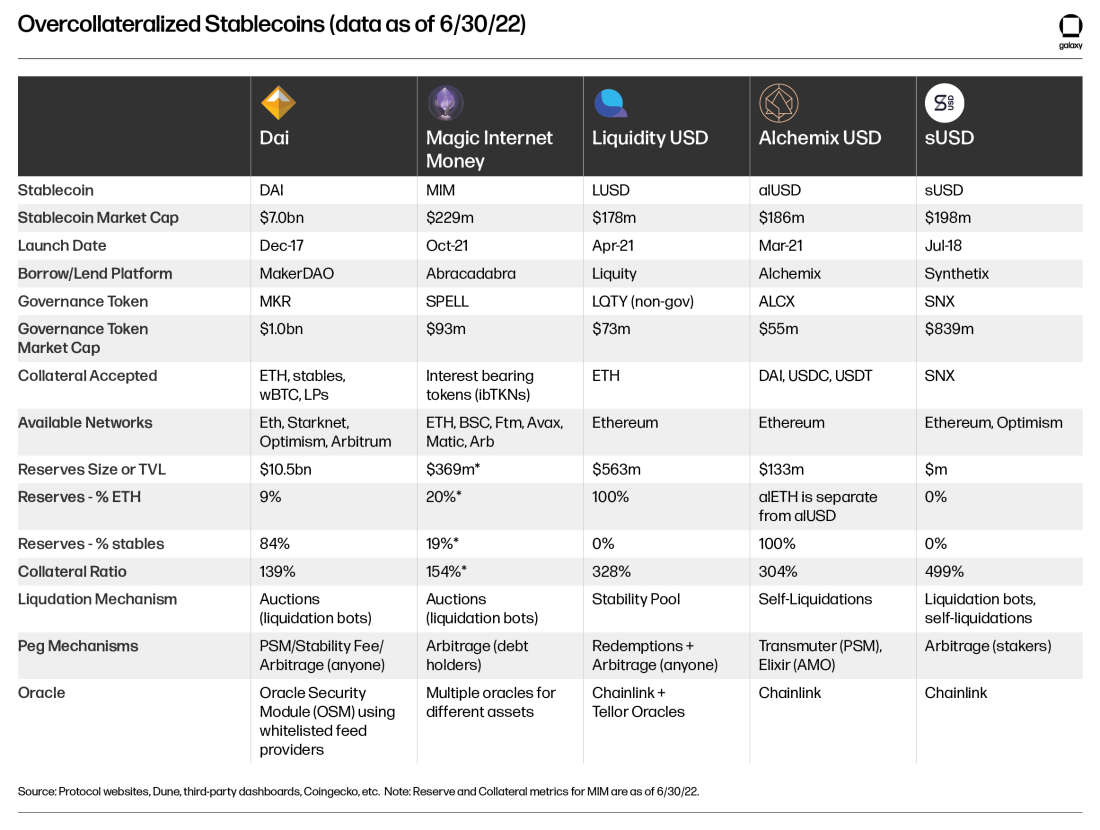

While these risk parameters and stability mechanisms can be effective during stable market conditions, they have also faltered during periods of extreme volatility. As a result, these models continue to be enhanced and innovated upon through new mechanisms and features. Below, we compare three of the leading overcollateralized stablecoins: MakerDAO’s DAI, Liquity’s LUSD, and Abracadabra’s Magic Internet Money (MIM).

MakerDAO (DAI)

MakerDAO was founded by Rune Christensen, who laid out the initial ideas for a “stable cryptocurrency” called eDollar in 2015 that drew inspiration from previous stablecoin iterations such as bitUSD and NuBits. The protocol’s name, Maker, refers to the importance of needing “Market Makers” to have sufficient liquidity for the protocol to function. In December 2017, the Maker protocol launched DAI on the Ethereum blockchain. MakerDAO initially only accepted ETH as collateral to generate Single-Collateral DAI (now called “SAI”) before the protocol was upgraded two years later to allow for multiple collateral asset types with the creation of Multi-Collateral DAI (DAI).

DAI is created and stabilized through Maker Vaults. Users use interfaces such as Oasis Borrow to deposit accepted collateral types and generate DAI. The specific risk parameters, including collateralization requirements and liquidation ratios per asset type, are determined through the Maker governance mechanism, in which MKR holders vote on changes.

Borrowers are charged a stability fee that represent interest on the loan and continuously accrues. Users must pay back the DAI borrowed as well as the stability fee to fully retrieve their deposits. When there is an oversupply of DAI, the stability fee can be increased to encourage borrowers to repay their loans and lessen the supply of DAI. Similarly, when there is excess demand for DAI, the stability fee can be decreased to incentivize borrowers to mint new DAI. Changes to the stability fee are also determined through the Maker governance mechanism.

Liquidations Process

The liquidation process plays an important role in maintaining the integrity of the Maker ecosystem. Protocol participants called Keepers are responsible for overseeing the liquidation of vaults that reach their liquidation ratio so that the protocol does not hold bad debt and become undercollateralized. In addition to receiving a liquidation fee, Keepers are incentivized to participate in liquidations through Collateral Auctions. In the first of two phases of Collateral Auctions, Keepers bid the maximum amount of DAI they are willing to pay for the vault’s collateral. This first phase enables Keepers to bid less DAI than the amount of collateral outstanding to receive the collateral at a discount. In practice, however, these auctions are normally automated by bots and bid up until the DAI offered is equal to the collateral outstanding.

Once the amount of DAI that will be paid is set, the second phase of the auction begins. During this phase, Keepers bid the minimum amount of collateral they are willing to accept in exchange for the DAI. These two phases create competition between Keepers to try and ensure that the maximum amount of DAI is paid for the collateral. Assuming the underlying collateral does not drastically drop in value, the Keeper that wins a collateral auction is able to purchase the collateral at a discount since all vaults are overcollateralized.

In the case of extreme market conditions, MakerDAO also has an emergency shutdown feature enabling MKR holders to deposit a set amount of MKR in order to freeze the protocol and allow vault creators to recover any collateral not backing outstanding debt.

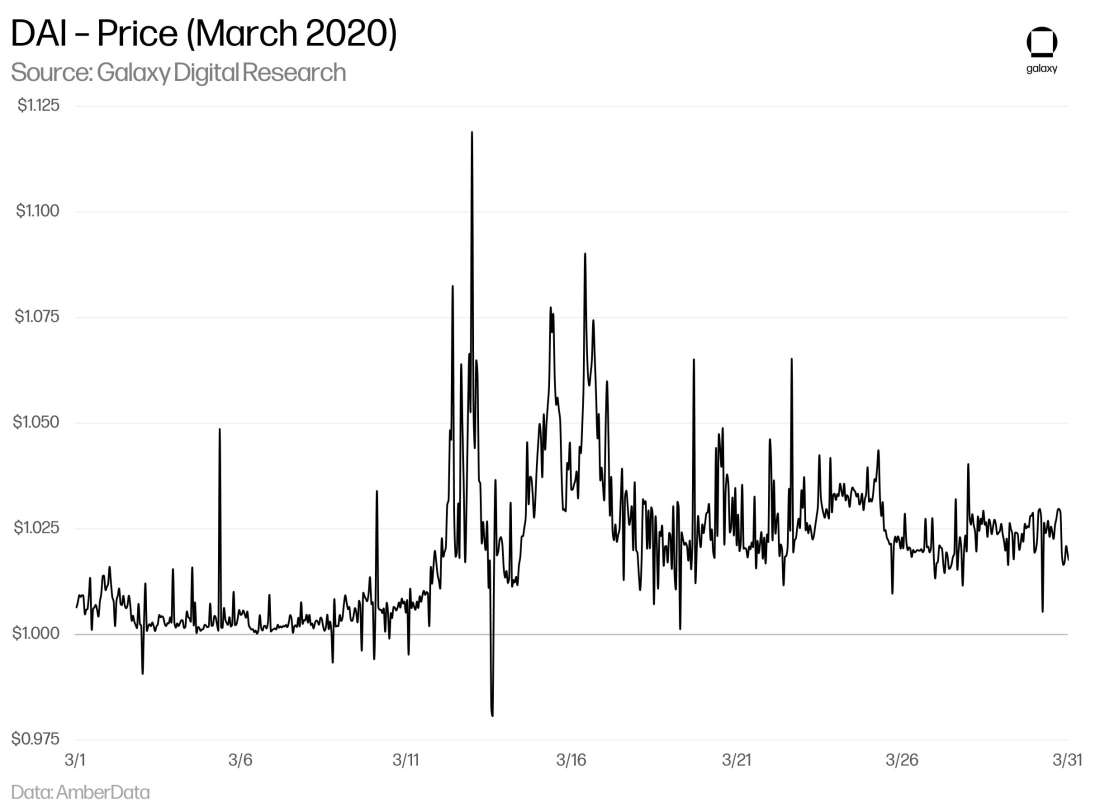

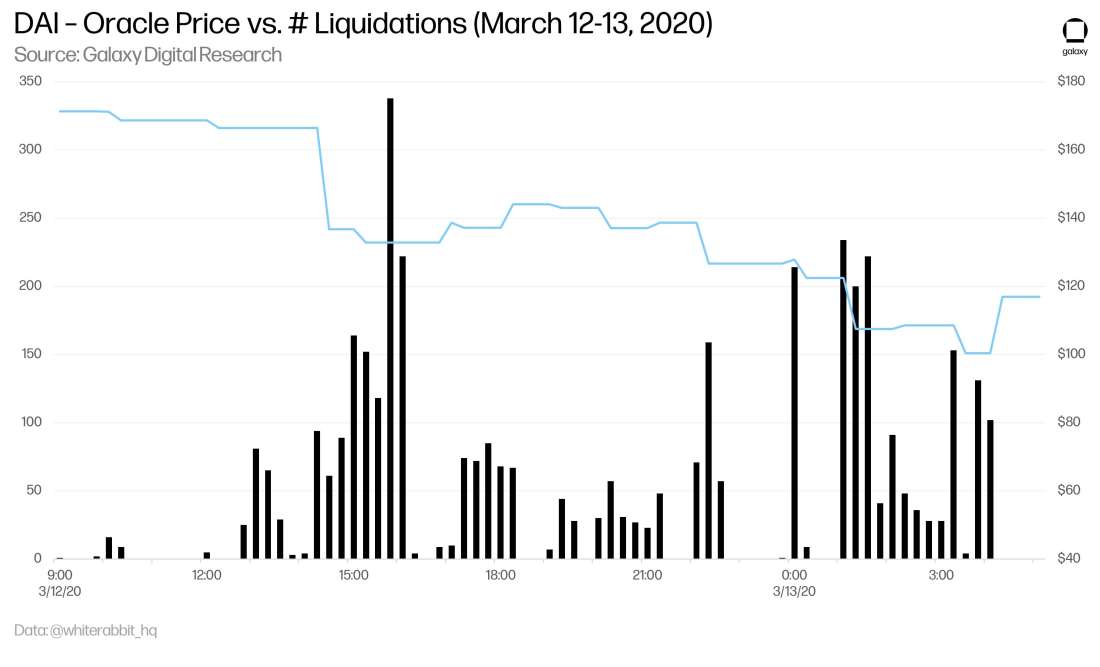

MakerDAO’s Black Thursday

On Thursday, March 12, 2020, DAI lost its peg to the dollar in an event referred to as Black Thursday. Amidst a broader selloff in digital assets and other risk assets in response to the closing of the global economy in the early days of COVID-19, Ethereum dropped from $193 to $95 in less than 24 hours. This dramatic drop in price corresponded with a rapid rise in Ethereum gas fees, resulting in a breakdown in Maker’s liquidation process. As users raced to pay back their loans to prevent from being liquidated, demand for DAI surged with the price reaching more than $1.10 at its peak.

However, the rise in Ethereum gas fees and long transaction queues also prevented Maker price oracles from updating in a timely manner. By the time the oracles’ transactions could go through, the price of Ethereum had dropped significantly, leading to the liquidations of several Maker vaults that saw LTVs fall below the liquidation threshold. Rather than pay the normal 13% liquidation penalty and lose a portion of their collateral, 320 vault owners lost 100% of their collateral.

Compounding the issue, Keepers that normally would have participated in collateral auctions to pay back the debts were unable to get their transactions through without paying exorbitant gas fees. This enabled other bidders to step in with higher gas fees to bid on liquidated vaults with no competition. As a result, 36% of all vault liquidation auctions were won with zero bids. A single liquidator won 1,461 auctions and more than 62k ETH for close to zero DAI, resulting in 6.65m of unbacked DAI. To re-collateralize the protocol, the Maker community opted to print additional MKR governance tokens and auction them off for DAI (Maker calls this a debt auction).

Improvements to the protocol after Black Thursday

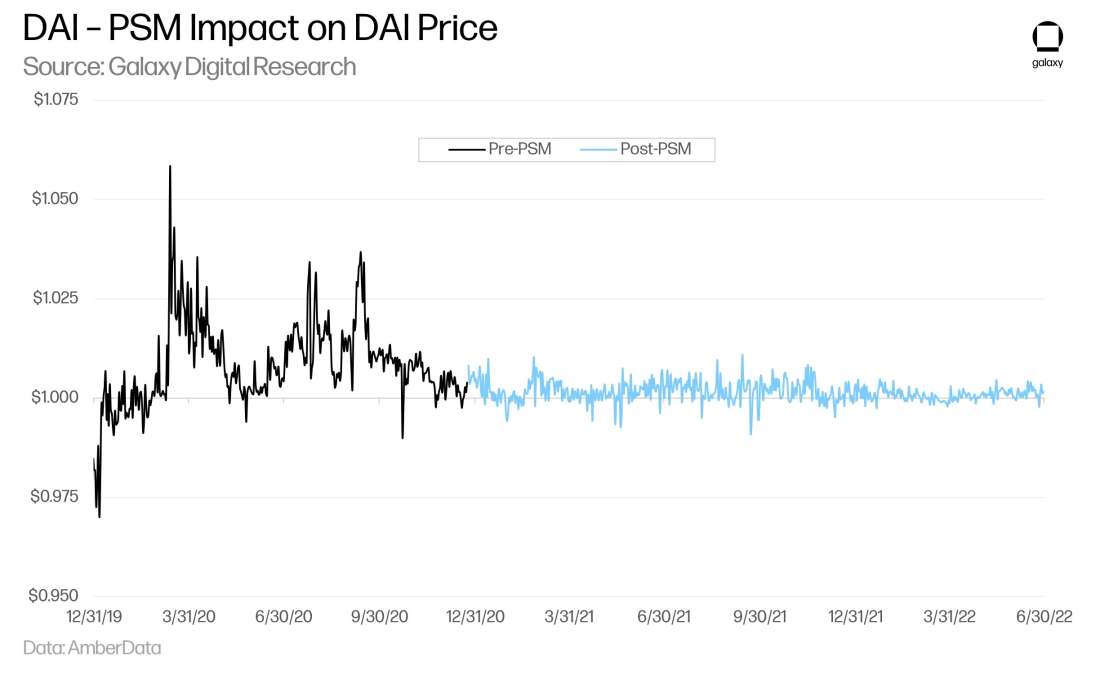

To prevent a similar event from re-occurring, Maker implemented several changes to the protocol. The most significant improvement introduced an arbitrage facility called the Peg Stability Module (PSM), a DEX through Maker which enables users to mint new DAI against stablecoins (incl. USDC, USDP, or GUSD) at a 1:1 rate. The PSM enables users to instantly swap US-pegged stable coins for DAI at a 1:1 rate (less a small fee). This mechanism has the benefit of enabling arbitrageurs to buy and sell DAI for a profit when the peg deviates from $1 without needing to open a vault and overcollateralize a position. It also increases the amount of DAI in circulation that is backed 1:1 with other reliable stablecoins (as opposed to volatile crypto assets). Since its introduction, the PSM has led to a significant reduction in DAI volatility, accounting for a 70 basis points decline in intra-day volatility.

Maker also implemented a surplus buffer, a pool of excess capital to ensure the protocol’s ability to cover any accumulated bad debt. Once that buffer is met, any surplus DAI the protocol earns is auctioned to MKR holders. MKR tokens are then burned in exchange for the surplus DAI, simultaneously rewarding MKR holders by decreasing its outstanding supply. Other improvements following Black Thursday included the addition of USDC as an approved collateral and safeguards to prevent auctions with only single bidders from closing.

Other key MakerDAO initiatives:

DAI Direct Deposit Module (D3M): In November 2021, Maker launched the D3M to expand DAI's presence outside of just Maker by providing DAI to other lending protocols. To date, D3M has only been implemented on Aave, but Maker has begun exploring the possibility of implementing D3Ms on Compound, TrueFi, and Maple Finance. Collateral deposits on Aave that are used to borrow DAI are indirectly used to maintain DAI's backing in the Maker Protocol. Maker benefits by earning additional income that's earned on the deposited DAI on these protocols and because DAI remains competitive with centralized stablecoins (e.g. USDT and USDC) through lower borrow rates. Following a collapse in the stETH-Eth peg in June, MakerDAO voted to temporarily suspend its Aave D3M initiative as $100m in DAI had been borrowed using stETH as collateral.

Multi-Chain: Maker has also begun to enable DAI’s use on other Ethereum Layer 2 protocols. To date, DAI token bridges have been deployed for Optimism, Arbitrum, and Starknet. Maker’s multi-chain strategy is aimed at growing DAI’s overall capture of the stablecoin market-share by enabling users on L2s to seamlessly use DAI.

Real World Assets (RWA) Initiative: In 2021, Maker began accepting RWA—or off-chain assets—as collateral to borrow DAI. The primary motivation of the RWA initiative is to build integrations between DeFi and TradFi to help scale DAI and improve the reserve composition of Maker with longer duration assets. They require complex legal agreements that are subject to regulation, the use of third parties that introduce counterparty risk, and extensive due diligence that cannot completely mitigate factors like credit and liquidity risk. A secured deal with Centrifuge, for example, enables RWAs to be securitized as NFTs to then used as collateral against DAI borrowings. Other deals have been with companies including Tesla and banks Huntingdon Valley Bank and Societe Generale.

Reserve Composition:

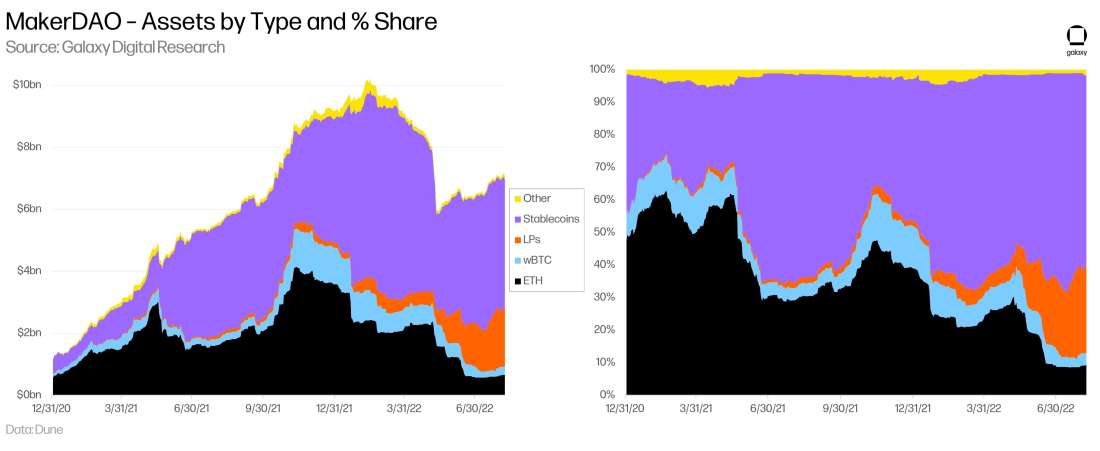

As of July 31, 2022, MakerDAO had 7.5bn DAI in circulation with $10.4bn in TVL, representing a collateralization ratio of ~140% and having a debt ceiling of 9.3bn DAI – meaning an additional 1.8bn DAI could be minted across all vaults based on the prevailing risk parameters.

Over time, Maker’s reserve composition has shifted from only ETH to acceptance of a variety of assets including wBTC, UNI, LINK, YFI, MANA, MATIC, and even UNI LP tokens (i.e. DAI/USDC LP). Through stablecoin vaults and the PSM, Maker also accepts USDC, USDP, and GUSD.

According to DaiStats, as of July 31, USDC directly accounted for 50% of total DAI collateral, though this figure may be understated though given USDC is also present in several LPs such as Uniswap DAI-USDC LPs. When taking these into account, USDC either directly or indirectly backs ~65% of DAI.

Criticisms of DAI

While the PSM has succeeded in strengthening DAI’s peg and reducing its volatility, it has faced some criticisms for leading to DAI’s outsized backing by USDC and fiat-backed stablecoins. Since the introduction of the PSM, DAI’s collateral mix has increasing shifted to centralized stablecoins. The risks of the centralized stablecoins as it relates to freezing assets or potential censorship are extended to DAI with Maker’s acceptance of centralized stablecoins as collateral deposits. Some critics argue that MakerDAO and DAI are facing an existential risk posed by the PSM and USDC – if regulators potentially demand significantly increased blacklisting or freezing of USDC, or if they force an actual whitelist that inhibits free transferability of USDC, then the majority of DAI’s backing would be unavailable to cover Maker’s liabilities, leading the system to become insolvent. Said another way, MakerDAO was created to function as a decentralized stablecoin system, and relying on centrally-issued assets for collateral undermines the system’s stated purpose and core value proposition.

Other Overcollateralized Stablecoins

Liquity (LUSD)

Liquity is a decentralized borrowing protocol that enables users to take interest-free loans denominated in its stablecoin LUSD using ETH as collateral. By removing a variable interest rate, users have more certainty over their future borrowing costs. Liquity compensates for a lack of an interest rate by charging dynamic borrowing and redemption fees ranging from 0.5% to 5% depending on the rate of issuance/redemptions during a given time period. These dynamic fees influence the level of borrowing activity. The one-time fee model can be beneficial for long-term borrowing as the fee is amortized over time, but it can be less-than-ideal for extremely short-term loans. Liquity’s founder has previously stated that LUSD is “not optimized for maintaining absolute price stability. Its main purpose is to offer sufficient stability to borrowers while serving as a base currency in other DeFi applications.” Instead, the protocol focuses on enhancing user’s ability to set their own risk parameters without having to abide by a broader protocol monetary policy (i.e., DAI’s stability fee).

Liquity relies upon the Stability Pool to ensure the protocol remains solvent. The Stability Pool takes LUSD deposits to repay undercollateralized debts, acting as the first line of defense for maintaining system solvency. When a trove, or a vault, is liquidated, LUSD is burned from the stability pool to repay the debt, then the entire ETH collateral from the trove is transferred to the Stability Pool to be split among pool depositors. In effect, Stability Pool depositors lose a portion of their LUSD deposits in exchange for a pro-rata share of the liquidated ETH collateral. Because collateral pools are liquidated just below 110%, stability pool depositors should receive more collateral (in $ value) than the portion of their LUSD burned.

The stability pool enables any depositor to assume some of the credit risk typically borne by the protocol from trove owners that take out LUSD loans. Stability pool depositors also directly benefit from liquidations across the protocol – rewards that typically would go entirely to liquidation bots on other protocols. These rewards can be especially rewarding during steep market selloffs when multiple troves are liquidated. Trove owners may also assume default risk even if their individual trove is far from liquidation – in the event the stability pool runs out of funds, then the protocol will utilize a secondary liquidation mechanism that redistributes the debt and collateral from liquidated troves to all other troves.

Magic Internet Money (MIM)

Abracadabra.money is a cross-chain DeFi lending protocol founded by Daniele Sestagalli. Abracadabra uses Sushi’s Kashi Lending Technology to enable users to borrow stablecoin Magic Internet Money (MIM) against interest-bearing tokens issued by third-party protocols, such as tokens representing deposits into Yearn Finance or Curve. Interest-bearing tokens allow the value of the underlying collateral in the protocol to continue to increase over time as they earn yield.

Abracadabra.money provides borrowers with a user-friendly interface to isolated lending markets, charging a fixed interest rate and displaying the liquidation price of their collateral deposits. Abracadabra.money supports leveraged yield farming strategies for its borrowers, including features such as a built-in leverage option which utilizes flash loans to replicate the repetitive process of using borrowed funds as deposits to enable more borrowings—all in one easy step for users. Abracadabra also accepts non-interest-bearing collateral to be used in automated yield-enhancing strategies through Degenbox. As the name indicates, the strategy was especially attractive to degen yield farmers looking to earn yield by leveraging their UST. It attracted significant liquidity, but also increased the protocol’s exposure to risk.

During the collapse of UST, the price of MIM fell as low as $0.91 as the rapid drop of UST prevented the protocol from liquidating UST collateral fast enough, leading to an accumulation of $12m in bad debt. MIM had also previously lost its peg in January 2022 after it was revealed that Daniele Sestagalli was working with Michael Patryn, founder of fraudulent Canadian exchange Quadriga CX, on another DeFi project Wonderland. This news concerned MIM holders and led many to exit their positions, including Alameda Research, which withdrew more than $500m worth of MIM from a Curve pool. The sudden withdraw of liquidity led MIM to drop to $0.97 for several days in May before it eventually returned to $1.

Others:

alUSD (Alchemix). Launched in February 2021, Alchemix is a lending protocol that offers its borrowers self-repaying loans that are paid down over time. Asset deposits on Alchemix are then deposited in Yearn vaults and the total accumulated yield can be harvested periodically to proportionally pay down depositors’ loans (with 10% of generated yield going to Alchemix as a service fee). Borrowers take out loans in the form of synthetic tokens (alAssets) such as alUSD, which can be minted against DAI, USDC, and USDT deposits. alUSD loans require a 200% collateralization ratio on stablecoins (i.e., max LTV ratio of 50%). The protocol targets a minimum 0.998 ratio for alUSD and alETH pegs, which is maintained through Alchemix Transmuter, a backstop for the peg (similar to Maker’s PSM) that enables alUSD deposits to be converted to DAI.

sUSD (Synthetix). Built on Ethereum and Optimism, the optimistic rollup layer 2 built on Ethereum, Synthetix is a derivatives platform that enables the issuance of synthetic assets, including its dollar-based stablecoin Synthetix USD (sUSD). Borrowers can mint sUSD or other “synths” by staking Synthetic’s SNX token as collateral. Synths are backed by a 400% collateralization ratio (borrowers will be unable to claim rewards on staked assets if the collateralization ratio falls below 400%). If the collateralization ratio falls below 200%, the accounts are flagged for liquidation. Synthetix has a liquidation timer of 72 hours to permit borrowers to improve their positions back above 400% before liquidations are initiated.

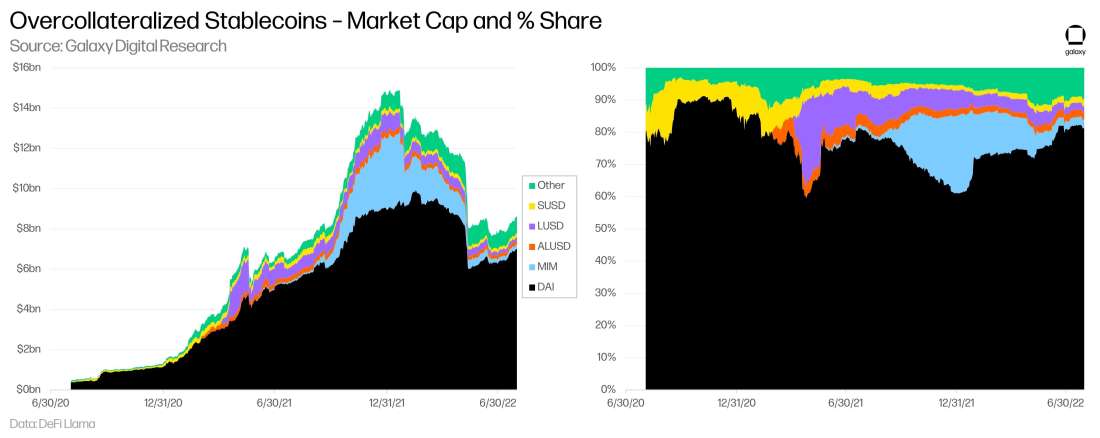

Competitive Dynamics of Overcollateralized Stablecoins

So far, overcollateralized stablecoins have failed to see the same level of adoption or competition seen among fiat-backed stablecoins. Maker is currently the most popular DeFi protocol as ranked by TVL, but it has faced heavy competition from other long-standing borrow/lend platforms including Aave and Compound. Up until now, Maker has been the only one in that group to launch its own stablecoin, but that may soon change following a new governance proposal in July for Aave to launch its own stablecoin, GHO. And, to date, no decentralized over-collateralized stablecoin has seriously challenged Maker’s dominance on that product.

Compared to fiat-backed stablecoins, which have much less flexibility to differentiate themselves, overcollateralized stablecoins compete not just on price stability and liquidity, but also on specific features of the stablecoin asset, including yield, rates, accepted collateral types, and the entire user experience of the borrow/lend platform.

Depositors into overcollateralized stablecoins may see a varying range of acceptance of multiple asset types with varying deposit rates offered between platforms. Borrowers of stablecoins through lending protocols may be charged interest rates that are variable, high-fixed, low-flat, zero, or even negative and self-repaying interest depending on the deposited collateral and lending platform. These platforms can also integrate varying levels of yield, which can come directly from protocol revenues or from other platforms that integrate the asset.

To influence the overall reserve profile behind overcollateralized stablecoins or to affect their prices in the event of de-peggings, lending protocols typically implement changes to incentives structures. The most common strategy is to influence interest rates. Higher interest rates can be implemented to attract more liquidity from depositors (which usually comes at the expense of borrowers). Interest rates are typically based on preset parameters such as the availability of liquidity and utilization rates, but they can be adjusted through governance changes. Overcollateralized stablecoins ideally would have deep enough liquidity to maintain price stability through preset limits and rate structures, but changes to risk parameters are often necessary. In these cases, openness in communication behind protocol changes are important or else overcollateralized stablecoins may lose their benefits of transparency over fiat-backed stablecoins.

Financial Analysis of Overcollateralized Stablecoins

Peg Stability

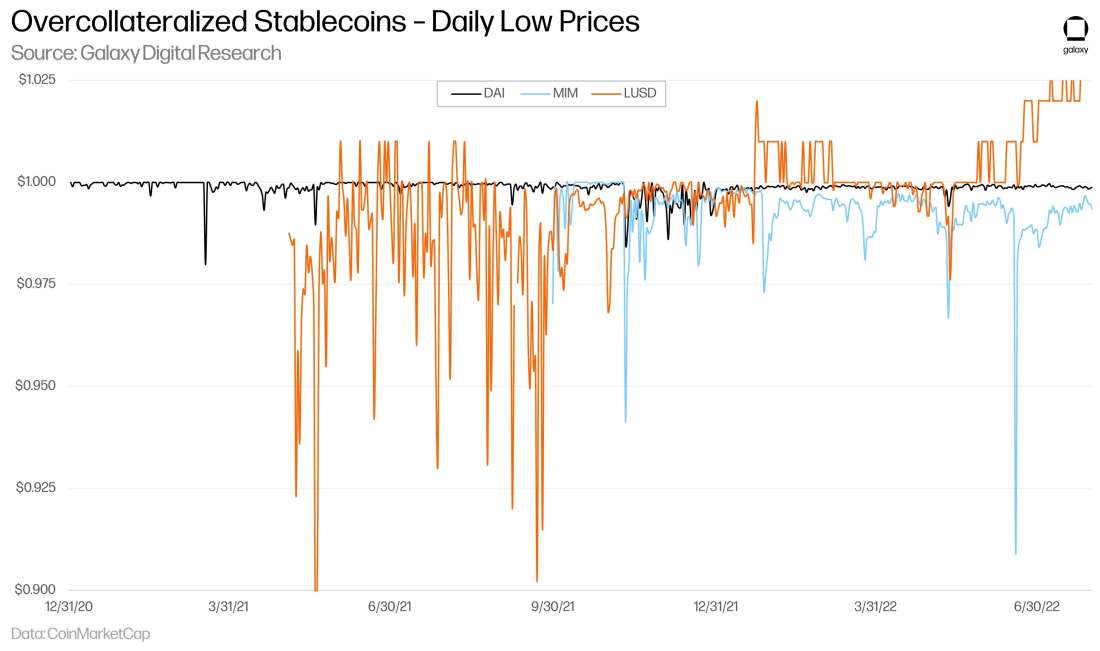

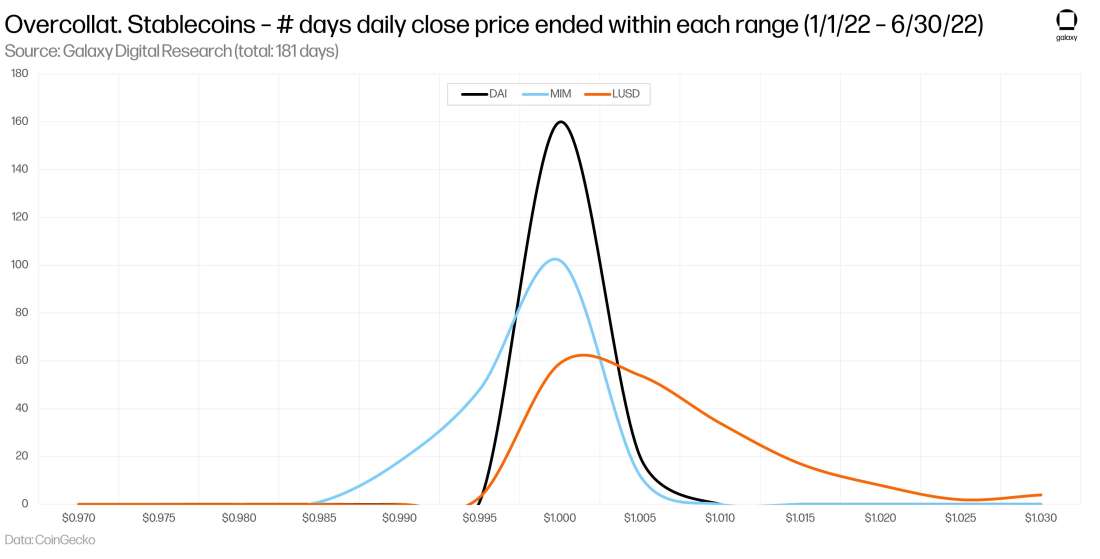

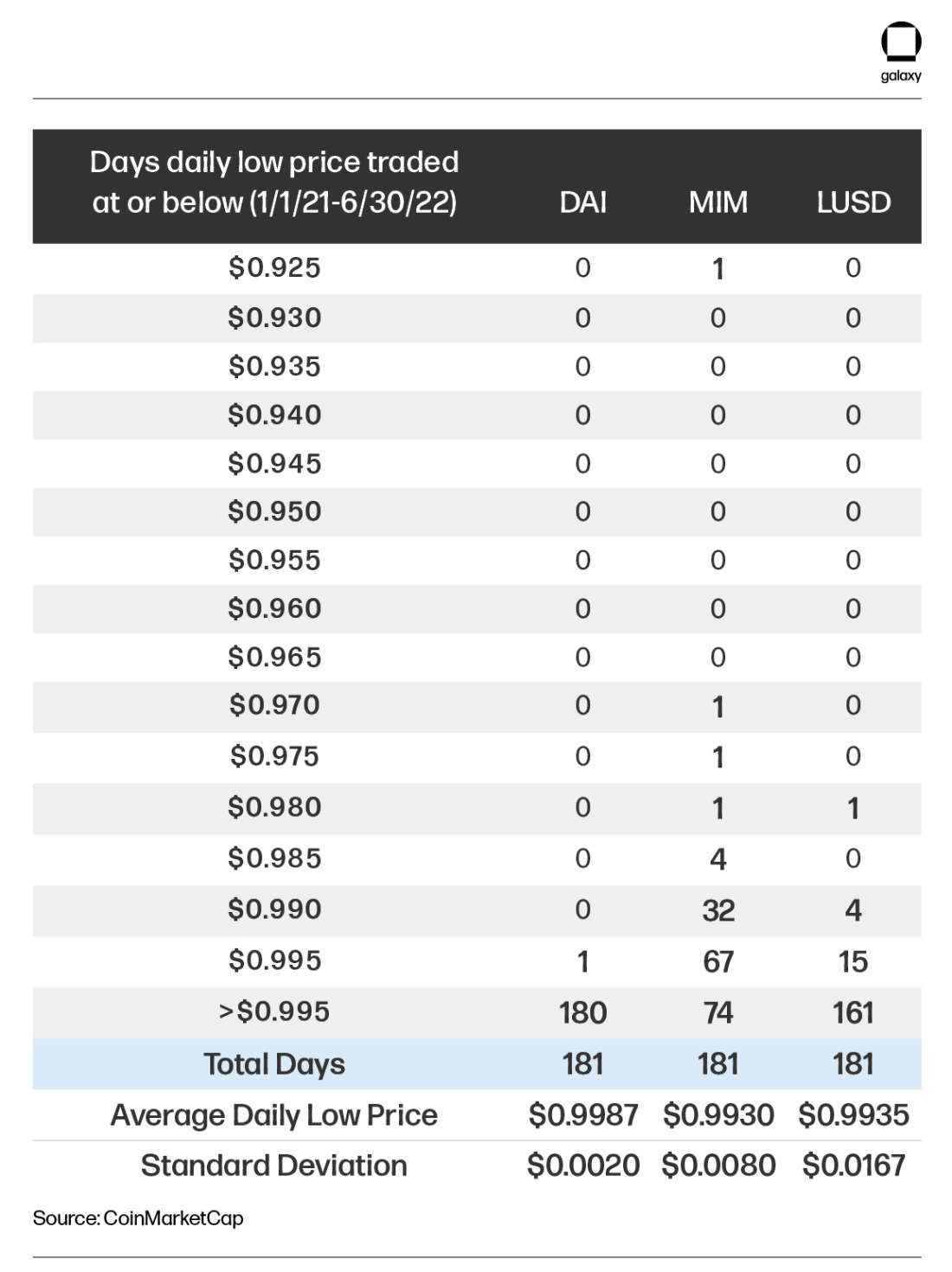

DAI has been the most stable in its select peer group over 1H22 with 160 out of the 181 days that its closing price fell between $0.9975-$1.0025 and 20 days that its price closed in the $1.0025-1.0075. The daily closing prices of MIM has been skewed more negatively with 67 days out of 181 days that it has closed below $0.9975. Since launching in October 2021, MIM has consistently experienced price volatility with periodic de-pegging events occurring almost monthly, including its most significant de-pegging experienced in June. On the other hand, the daily closing prices of LUSD has been positively skewed with 119 days in 1H22 that it has closed above $1.0025. LUSD has improved its price stability significantly since launching in April 2021, though it does not prioritize stability for upside deviations to the same degree as downside deviations. Notably, overcollateralized stablecoins have almost all experienced significant volatility early in their launches (DAI is no exception here). Those that survive, though, have tended to level out over time.

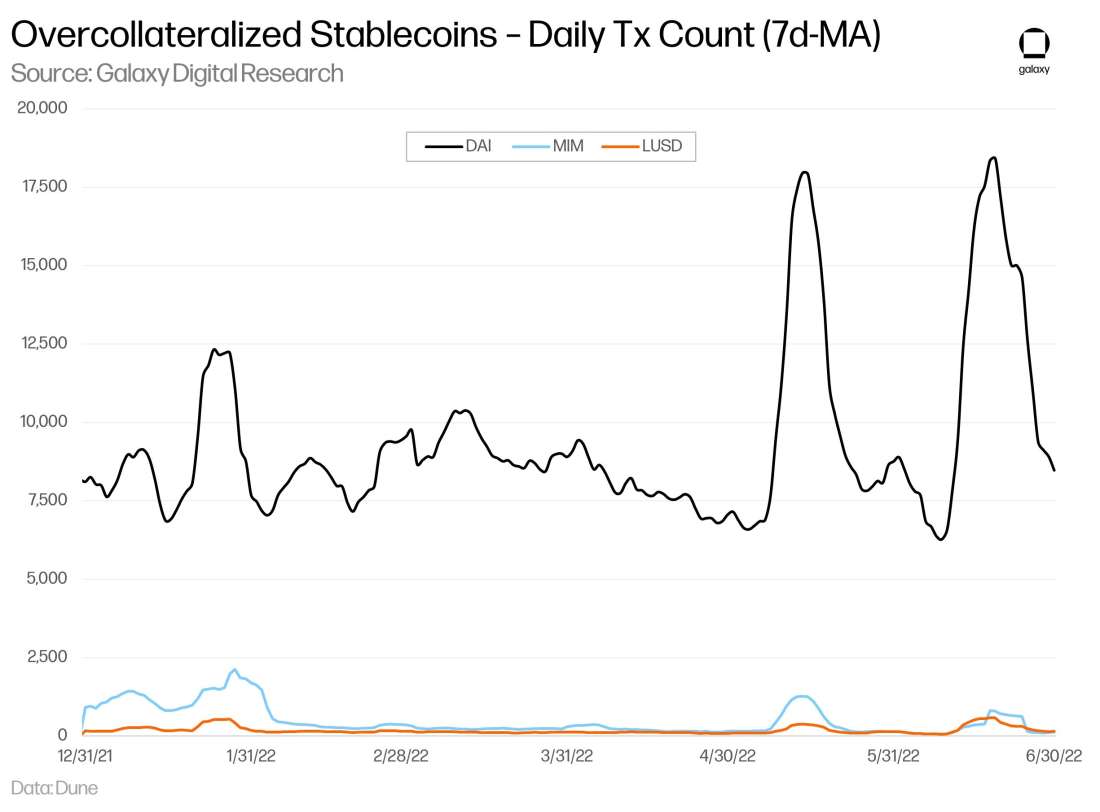

Usage

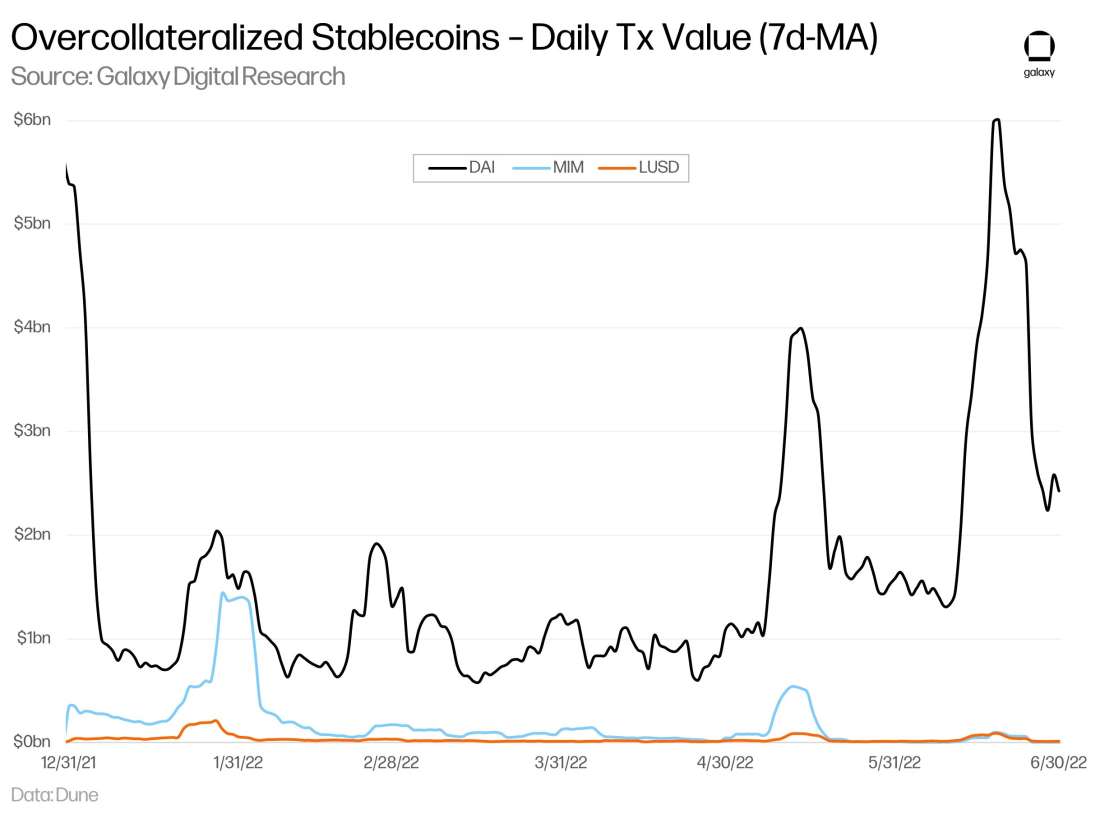

DAI stands well above MIM and LUSD in both transaction count and volume. MIM and LUSD come in at approximately 5% and 2% of the transaction count of DAI. Activity levels with DAI and LUSD have generally been increasing throughout 1H22 seemingly at the expense of MIM, whose activity levels have peaked early this year and have been sliding since.

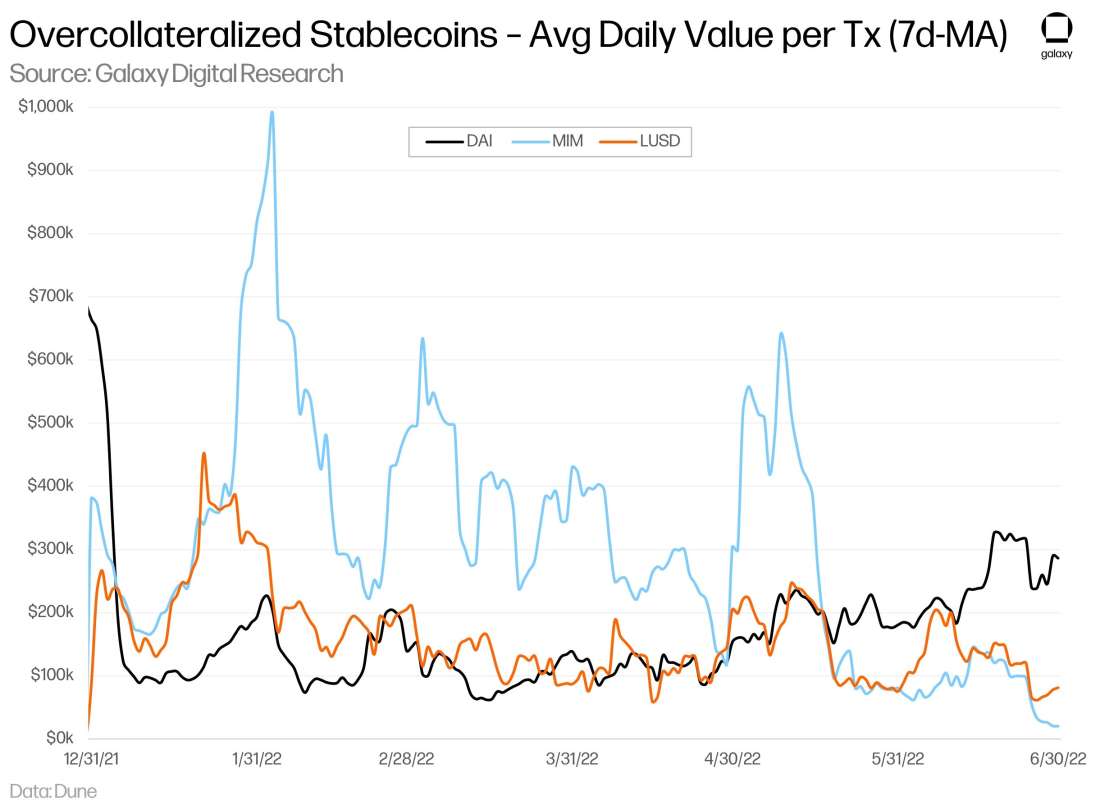

DAI’s average transaction value was $164k/tx during 1H22 as it consistently increased since March. MIM started out the year with a much higher average transaction value than DAI, though it has experienced a downward trend since. LUSD saw either higher or comparable average transaction values with DAI through the first 4.5 months of 1H22 though it has since trended in the opposite direction.

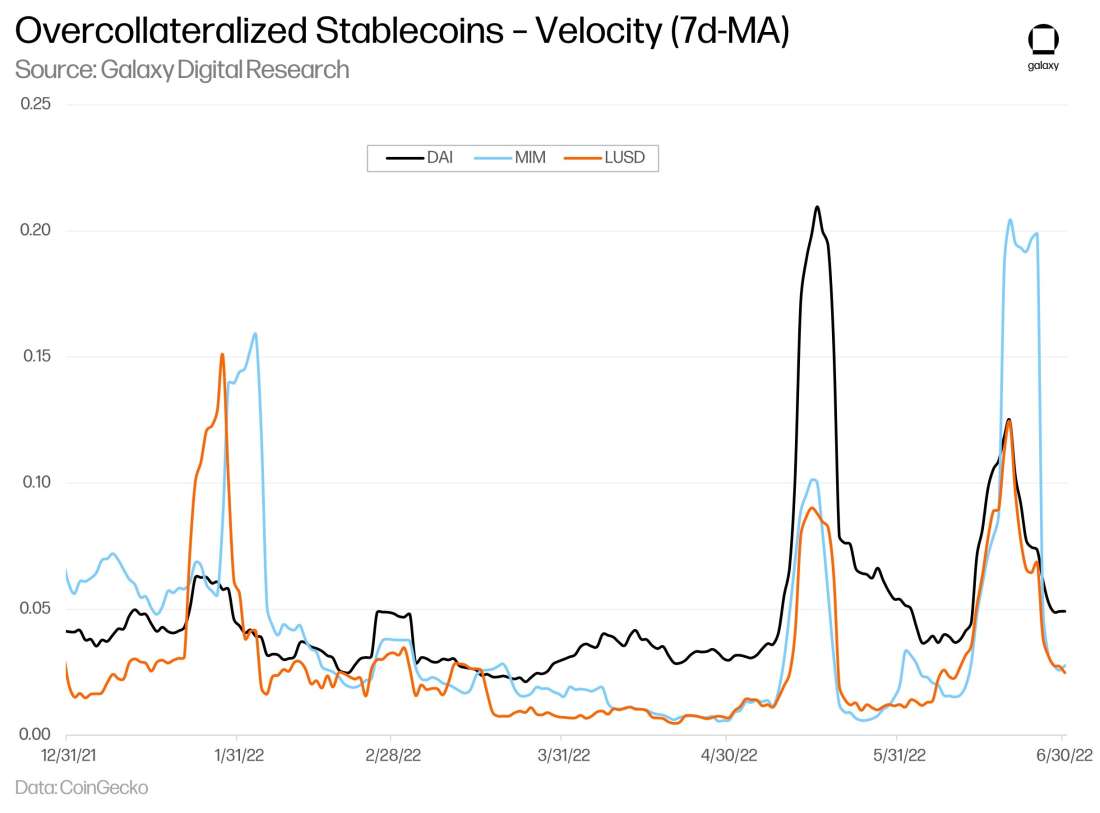

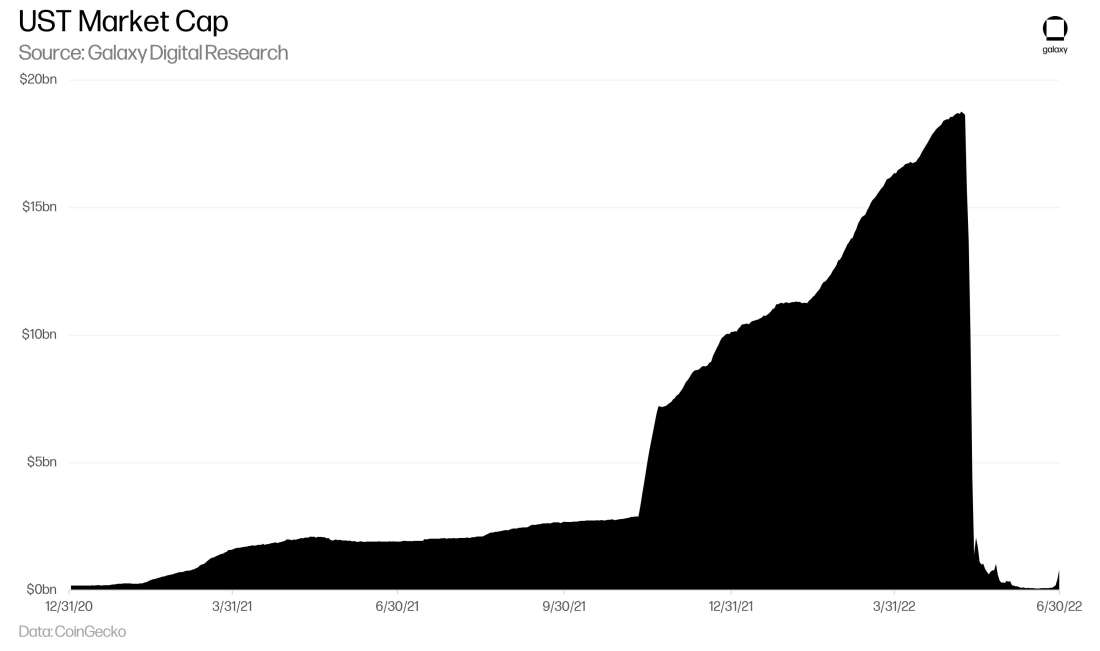

During 1H22, DAI experienced higher velocity than MIM and LUSD, averaging 0.049 vs. 0.042 and 0.030, respectively. DAI experienced the highest spike in velocity in the group following the collapse of UST, though MIM has experienced several periods of high velocity related to its de-pegging events with Danielle Sesta’s association with Michael Patryn in late January and then Abracadabra’s accumulation of $12m in bad debt.

Main Concerns with Overcollateralized Stablecoins

Reserves backed by centralized, censorable assets (e.g., USDC and USDT). Overcollateralized stablecoins take on some of the risks of the collateral assets that they accept. For example, the risks of the centralized stablecoins as it relates to freezing assets or potential censorship are extended to DAI with Maker’s acceptance of USDC for the PSM. This may be beneficial for maintaining price stability, but it limits the level of decentralization that overcollateralized stablecoins can achieve, reducing their overall value proposition.

Technical Risk. A failure of a protocol’s smart contracts, either through exploitation or design flaws, could disrupt the protocol’s ability to adhere to its risk parameters, leading to peg failures. Protocols are reliant on oracles to ensure accurate reference prices for the underlying collateral to feed into smart contracts. Price oracles may face risk of manipulation or infrequent updates that can cause reporting to be lagged. Protocols often rely upon Chainlink price feeds for ETH and can rely upon other oracles for other collateral assets including Uniswap v3 TWAP oracles or oracles operated by the asset team.

Capital inefficiency. Overcollateralized stablecoins are capital inefficient as they require a greater amount of collateral deposits for each issued token (vs. 1:1 for fiat-backed stablecoins). Maker recommends users in certain ETH vaults to maintain collateralization ratios above 200% with liquidation thresholds set at 150%. This would imply that users take out a maximum of 66% of their collateral value in DAI, which limits the speed at which these stablecoins can grow. The supply of overcollateralized stablecoins is heavily dependent on borrowing activity, which can quickly dry up in a downturn as it is highly correlated to traders seeking leveraged long positions, limiting their utility for other applications looking to integrate the stablecoin.

Algorithmic Stablecoins

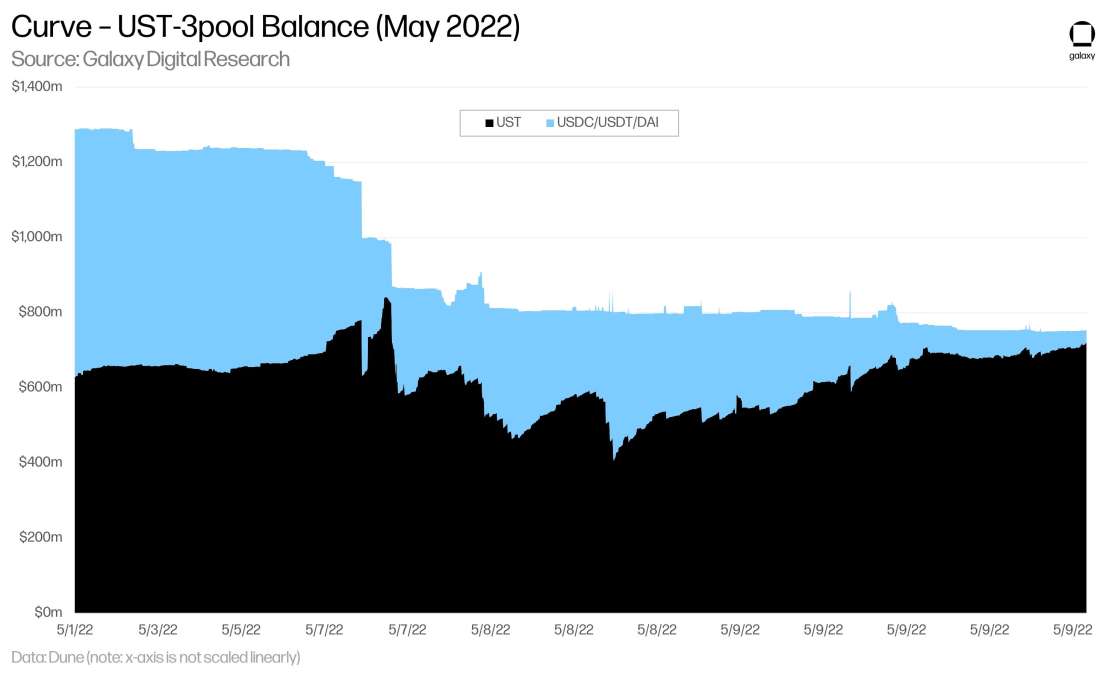

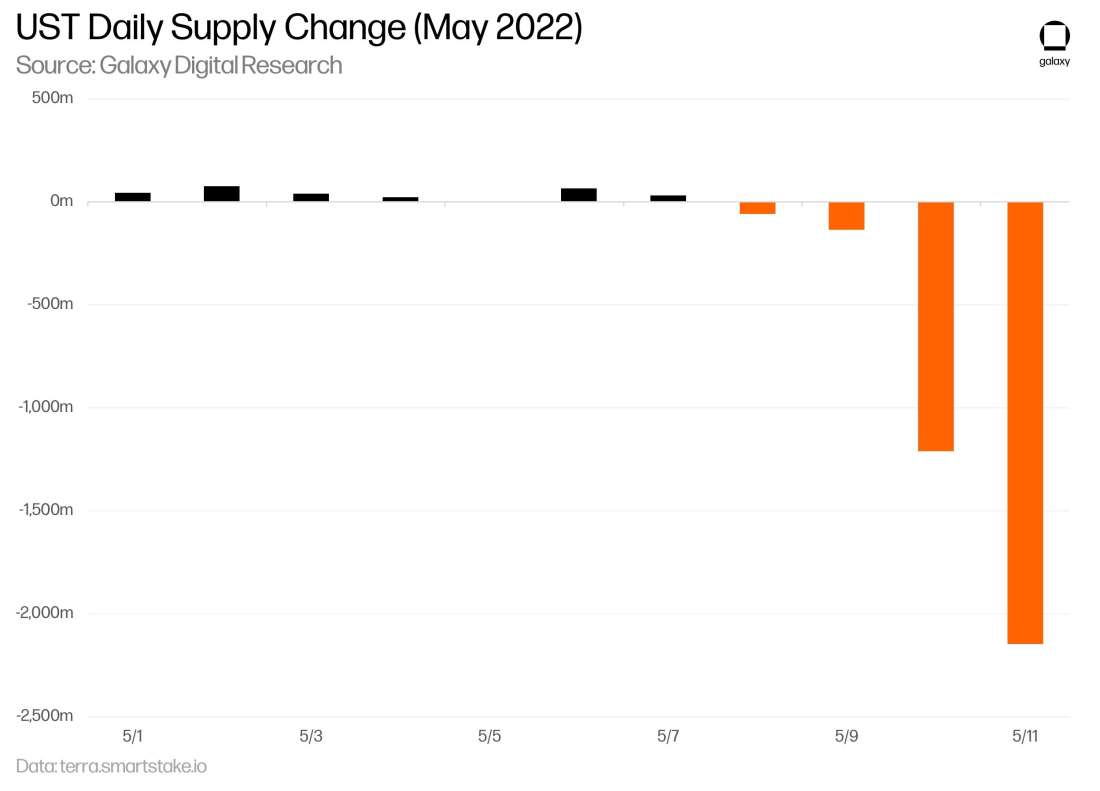

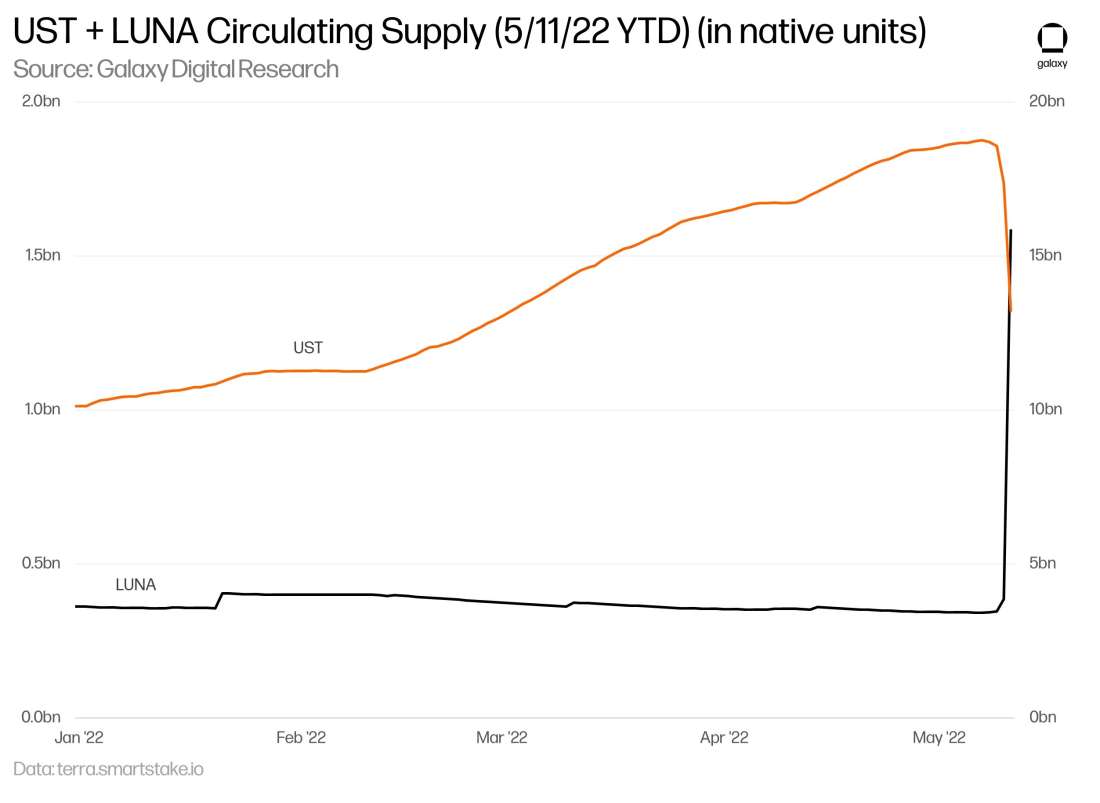

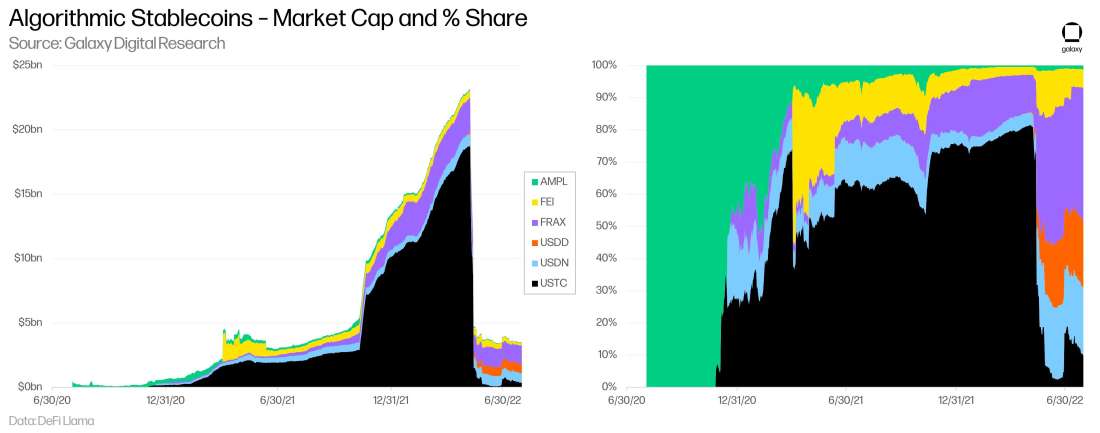

Algorithmic stablecoins attempt to address the centralization concerns of fiat-backed stablecoins and the capital-inefficiency concerns of overcollateralized stablecoins. Rather than being explicitly backed or fully collateralized, algorithmic stablecoins are designed to maintain price parity with a certain asset through market forces via smart contracts to increase/decrease supply.